Canada races to secure its Arctic frontier

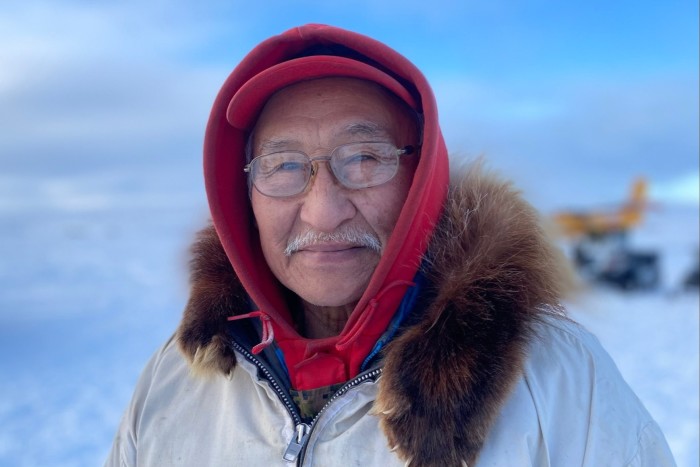

For the past 25 years Emmanuel Adam, a master corporal in the Canadian Rangers, has been the eyes and ears of Canada’s frontline in the Arctic.

But rather than spotting adversaries, Adam, a 72-year-old Inuvialuk from Tuktoyaktuk, is mostly seeing the climate change.

“It’s warm, it’s getting warmer,” he said during Operation Nanook, a military exercise held in early March. “This is more April weather, spring.”

Warm for Adam is minus 20C. It is cold enough to stop a phone working and freeze ink in a pen. At night it gets to minus 40C. Then there is the wind.

It is hard to imagine that this inhospitable tundra 200km north of the Arctic Circle is emerging as the new frontline in a geopolitical contest with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and China’s leader Xi Jinping.

US President Donald Trump’s shifting expansionist rhetoric along with the increased accessibility of the Arctic as a result of climate change, are putting this once off-limits region higher on the military agenda.

For General Jennie Carignan, Canada’s chief of the defence staff, its defence is a top priority.

“The Arctic is evolving and we can’t rely on the environment now to protect us as well as it could in the past,” she said. “So this is why we need to invest more, and we need to operate a better defence and take up our responsibilities in the Arctic.”

Canada’s Arctic defence strategy relies heavily on indigenous knowledge from Ranger units. The unique network of 5,000 semi-professional soldiers is spread across the vast region that makes up 40 per cent of the country’s landmass but is home to only 150,000 people.

Since 2007, Operation Nanook — the Inuktitut word for polar bear — a joint military exercise with allies including the US and European nations to “project force”, has been held annually with the Rangers in the high Arctic region.

Standing in the snow beside a helicopter somewhere between Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik, Carignan praised the Rangers’ 75 years of service to the country as she met a mix of Canadian, British and US special forces soldiers on the exercise, who spent several weeks living with the indigenous soldiers on this barren frontier.

“Very James Bond,” General Carignan said, inspecting a snowmobile with a mounted rifle.

At the Midnight Sun basketball court, which had been temporarily converted into an army mess hall, Major Andrew Melvin instructed a hundred or so young Canadian reservists and soldiers, many of whom had never left their home town let alone visited the Arctic, on the seriousness of their surroundings.

“You will die out here,” he said. “The only thing between you dying out there is the Ranger, so listen to them.”

While the environment may be an enemy, Nanook’s focus has been on competition for the Arctic from China and Russia — and now there is increasing concern over Trump’s interest in the region.

The US president has chided Ottawa for not meeting its 2 per cent Nato defence budget commitment, has said he intends to “buy” Greenland and has repeatedly threatened to annex Canada via “economic force”. The threat has been underlined by the visit of vice-president JD Vance to “check out security” at a US military base in Greenland on Friday.

During the last Trump presidency, the US explicitly challenged Canada’s sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, which is becoming a busier shipping lane as the polar ice melts.

On a short layover in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, last week Carney reiterated that the passage remained Canadian “sovereign waters”.

With some academics predicting that the first “ice-free day” in the Arctic Ocean could occur before 2030, Major-general Steve Hunter, commander of Canadian Special Operations Forces Command, said the symmetry between climate change and resource contestation would bring new risks and a greater potential for disasters.

While “there’s a lot of economic interest from potential adversaries in the North” it would “be foolish to think the threat is tanks coming across the Arctic Circle”, he said, adding that resource competition and access to infrastructure were the region’s emerging vulnerabilities.

“We’ve spent a lot of the last 20 years in deserts around the world, so we are getting reacquainted with the complexities of this environment,” he said.

In the face of the growing threat, Prime Minister Mark Carney on March 18 announced $6bn for a new radar system to modernise the North American Aerospace Defense Command, (NORAD). Carney also committed troops to “take on a greater, sustained, and year-round” Arctic presence.

Ottawa is also acquiring 12 submarines, eight icebreakers and 88 F35 fighter jets as part of a 20-year $73bn programme to strengthen its defences.

Earlier this month, defence minister Bill Blair announced that Canadian Arctic military bases in Inuvik, Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories (NWT) and Nunavut’s capital, Iqaluit, would be bolstered as part of the plan.

Watching locals play ice hockey in Inuvik, Professor Whitney Lackenbauer, an honorary Ranger officer, said that while sovereignty was often talked about as if it were simply lines on a map; “I’ve always understood [it] as being everything that goes on within those lines”.

“It is the ability to control what’s going on in the region in the face of all these pressures,” he added.

Lackenbauer said the Rangers embodied the “shared sovereignties” that were fundamental to Canada’s Arctic defence.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Steve Bannon, an ideologue backing Trump, has called for US “hemispheric defence” of the Arctic, mostly due to Canada’s critical minerals.

Rare earth elements and critical minerals, a market dominated by China and integral to the digital economy and the transition to a low-carbon economy, are central to Trump’s interest in other parts of the world, including Ukraine and the Arctic.

The US Geological Survey, more than a decade ago, estimated that the region held 13 per cent, or 90bn barrels, of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 per cent of its undiscovered conventional natural gas.

While Canada has placed an “indefinite moratorium” on offshore oil and gas activity in the region, according to its new Arctic policy it is “willing to explore” the area for critical minerals, such as lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, copper.

Despite the threats from Washington, US air force Colonel Robert Donaldson, 109th Airlift Wing commander, said his soldiers remained “apolitical” as their focus was “interoperability” with allies, which is at the core of protecting the Arctic.

Speaking at Inuvik airport, Donaldson said training exercises such as Nanook, and working with “Canada, side by side” was critical because “if the flag does go up, we can respond accordingly and in tandem, in lockstep”.

But as as much as Canada and the US project force in the Arctic, so too do Russia and China, according to Jennifer Spence, director of the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School.

Russia already relies heavily on its Arctic region for mining precious metals and coal, as well as for oil and gas. China described itself as a “near-Arctic nation” in 2018 — but with no Arctic coastline, Beijing’s aspirations rely on partnerships with Moscow.

“The ‘no limits relationship’ (between Russia and China) is far from a no limits relationship,” she said. “There’s actually a lot of internal dynamics there. There’s a lot of complicated history and people should not forget that.”

“For a majority of the population in Canada and the US, the Arctic remains peripheral and poorly understood but for the Russians it’s an integral part of their economy, culture and history,” she said.

For Adam, the frontline of this global contest is simply home.

“This is the lifestyle I grew up with,” he said. “I enjoy being on the land and using it to its full extent.”

Cartography by Steven Bernard and Cleve Jones

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here