How Israel Deceived the U.S. and Built the Bomb

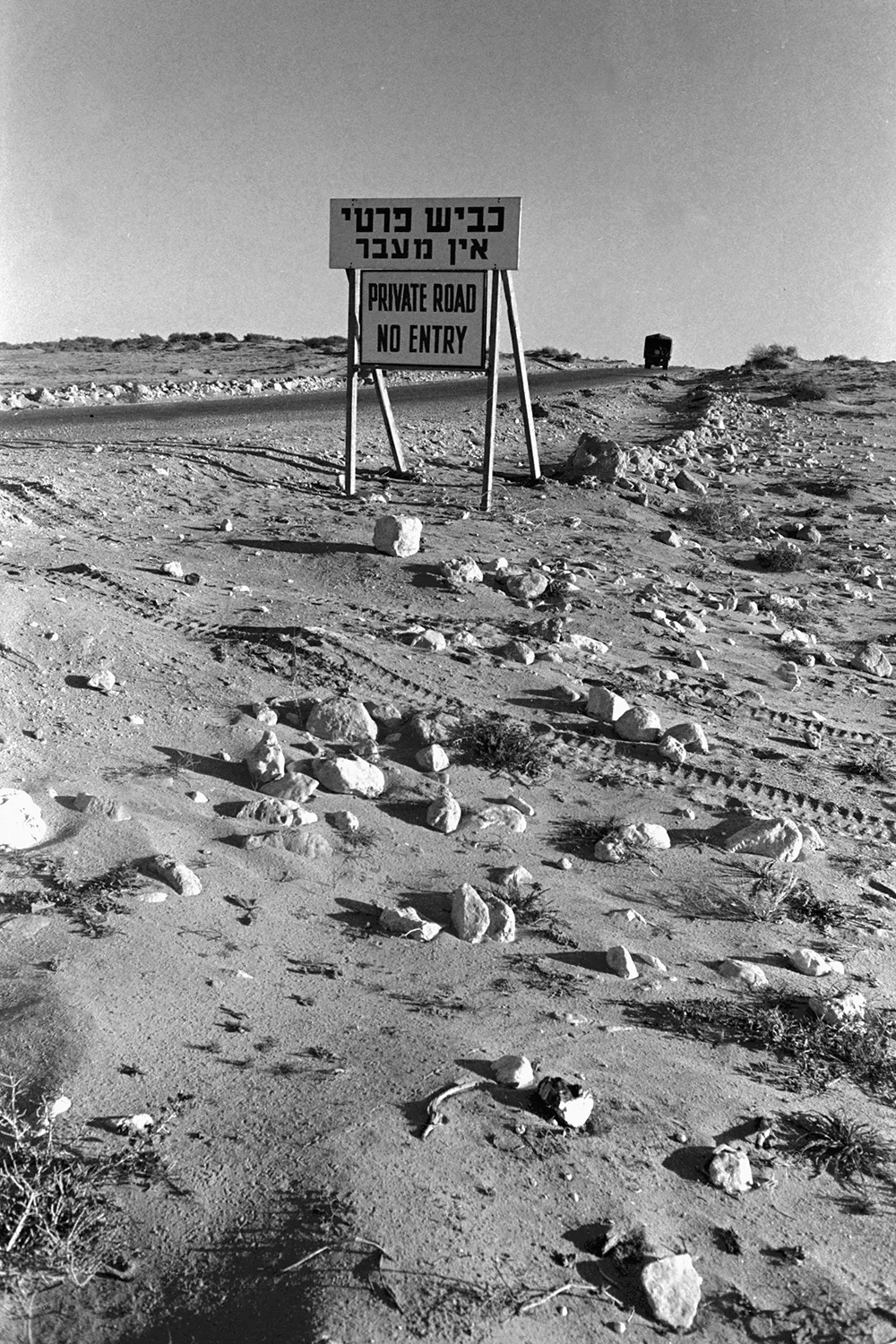

A sign at the entrance to the Negev Nuclear Research Center near Dimona, Israel, in an undated photo. David Rubinger/Corbis via Getty Images

Analysis

How Israel Deceived the U.S. and Built the Bomb

Newly declassified documents reveal how Israel operated under the noses of U.S. inspectors.

Iran’s nuclear activities have been on the front pages for years although it remains unclear precisely how close Tehran is to building its first bomb. Iran’s relative failure in preserving the secrecy of its weapons aspirations stands in sharp contrast to the experience of Israel, the first and only Middle Eastern state to acquire nuclear weapons. During the 1960s, Israel built the bomb in near-absolute secrecy—even deceiving the U.S. government about its activities and goals.

Israel’s first leader, David Ben-Gurion, initiated Israel’s nuclear project in the mid- to late- 1950s, establishing Israel’s nuclear complex at Dimona, during a period when only three countries had nuclear weapons. A decade later, on the eve of the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel secretly assembled its first nuclear devices.

Iran’s nuclear activities have been on the front pages for years although it remains unclear precisely how close Tehran is to building its first bomb. Iran’s relative failure in preserving the secrecy of its weapons aspirations stands in sharp contrast to the experience of Israel, the first and only Middle Eastern state to acquire nuclear weapons. During the 1960s, Israel built the bomb in near-absolute secrecy—even deceiving the U.S. government about its activities and goals.

Israel’s first leader, David Ben-Gurion, initiated Israel’s nuclear project in the mid- to late- 1950s, establishing Israel’s nuclear complex at Dimona, during a period when only three countries had nuclear weapons. A decade later, on the eve of the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel secretly assembled its first nuclear devices.

Against stiff U.S. opposition, led by President John F. Kennedy, Israeli leaders were determined to reach their goals. They saw the nuclear project as a commitment to ensure the country’s future—a “never again” pledge shaped by memory of the Holocaust. Audacity, trickery, and deception were key aspects of the relentless execution of Israel’s nuclear journey.

Last month, the George Washington University’s National Security Archive posted a new Electronic Briefing Book that includes 20 documents on Israel’s nuclear project. Those reports shed light on what the U.S. government knew about Dimona’s secrets and how Israel concealed them.

Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion rides in a car in Washington, D.C., on March 10, 1960, during a state visit.PhotoQuest/Getty Images

From the start, Israeli leaders conceived of the Dimona project as a secret within a secret. The first secret was the 1957 French-Israeli nuclear agreement that led to the creation of the nuclear complex. The two countries negotiated the agreement confidentially because both sides were aware of its sensitivity.

And then there was a deeper secret: the large six-story underground reprocessing facility, often referred to as a chemical separation plant, that would provide a capability to produce weapons-grade plutonium and remain concealed. Very few people on both sides of the French-Israeli agreement knew that inner secret.

Until now, the evidence suggested that when the United States discovered the Dimona project in the final months of 1960, it did not know this deeper secret. U.S. internal discussions focused on assessing the nature and motivation of the project, whether it was for weapons (i.e. plutonium production), power production, or research. While some in Washington suspected from the start that the Dimona project was about weapons production, they could not prove it; there was no smoking gun.

In general, the U.S. government had no detailed knowledge of the secret French-Israeli nuclear deal, much less that it included a French-designed reprocessing plant to produce weapons-grade plutonium using a chemical process applied to the reactor’s spent fuel, enabling the separation of plutonium from other radioactive products.

This uncertainty was reflected in the first Special National Intelligence Estimate about Dimona issued by the CIA on Dec. 8, 1960, which included a factual determination that “Israel is engaged in construction of a nuclear reactor complex in the Negev near Beersheba.” Yet it acknowledged that “a number of interpretations of the function of this complex are possible, including research, plutonium production, nuclear electric power generation, or combinations thereof” and suggested that “on the basis of all available evidence … plutonium production for weapons is at least one major purpose of this effort.”

A recently declassified report called “Israeli Plutonium Production,” created on Dec. 2, 1960, by the Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee, suggested that U.S. officials knew more. It posited not only the construction of a large reactor near Beersheba but also added that the project included a “plutonium separation plant.”

A section of the opening page from the 1960 “Israeli Plutonium Production” document.National Security Archive

The report did not explain how it reached that conclusion. However, by stipulating the construction of a separation plant, JAEIC indicated that Dimona’s purpose was not research but weapons. This document may be the first or only U.S. intelligence report that unequivocally found that the French-Israeli project included from start the two technological components required for a weapons program: a production reactor and a plutonium separation plant.

If U.S. intelligence knew—or at least presumed—that Dimona included a reprocessing capacity, it informed U.S. policy: The Eisenhower administration raised serious questions with the Israelis about the purposes of the Dimona project. But why that knowledge did not show up in subsequent intelligence products is a mystery, unless it was held so closely that only a few were aware of the facts.

All subsequent U.S. intelligence estimates on Dimona, from 1961 to at least 1967, treat the separation plant issue as a matter that required a new Israeli decision. Certainly, by the early to mid-1960s and later, both the State Department and the CIA subscribed explicitly to the view that Dimona lacked such a facility.

U.S. President John F. Kennedy receives a standing ovation as he walks into the State Department’s new auditorium to hold his first news conference since taking office, on Jan. 25, 1961. Kennedy spoke about Geneva negotiations with Russia over a nuclear test ban treaty.Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In his Knesset statement on Dec. 21, 1960, in response to U.S. pressure, Ben-Gurion confirmed the construction of the Dimona reactor but insisted that it was “a research reactor … which will serve the needs of industry, agriculture, health, and science.” Intelligence findings made the Eisenhower administration skeptical, and its public statements indicated surprise at the time of the reactor’s discovery. Denying a weapons pursuit, an angry Ben-Gurion told U. S. Ambassador Ogden Reid that “we are not a satellite of America … and will never be a satellite.”

Ben-Gurion’s statement became the basis of a deceptive cover story that Israel used for years whenever U.S. inspectors visited Dimona. According to the report from the first visit in May 1961, Dimona’s director, Emanuel (Manes) Pratt told the U.S. scientists that Dimona’s purpose was to gain “experience in construction of a nuclear facility which would prepare [Israel] for nuclear power in the long run,” based on a French-designed research reactor. They falsely told the U.S. visitors that Dimona was a broad-based technological enterprise for training Israeli scientists with most aspects of the nuclear fuel cycle for various peaceful purposes.

To make this narrative credible, Israel committed itself to a full deception campaign. That required not only the concealment of the underground separation plant, but also the camouflaging of other components at the Dimona site to provide a credible but false picture of the reactor and its use. This operation was politically and technically complex. Before the arrival of any visiting U.S. team, Dimona personnel invested weeks of efforts to make the deception believable. The new reports on the Dimona visits help us understand how that was done.

Between 1961 and 1969, the United States conducted eight inspection visits at Dimona; seven of them took place after Kennedy forced Israel to accept regular visits in 1963. For Kennedy, the value of the visits was twofold: political messaging and technical intelligence access. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, continued the effort.

An approximate site plan included in the 1961 Atomic Energy Commission document.National Security Archive

The Archive’s new publication includes the recently declassified full reports of the 1965 and 1966 visits, along with a preliminary report of the 1967 visit. During this three-year period, Israel reached significant nuclear milestones. By 1965, Israel had completed its super-secret underground separation plant; by 1966, it started to produce weapons-grade plutonium; and on the eve of the 1967 war, Israel assembled its first nuclear devices.

Yet all reports of the U.S. visits in this period claimed they found no direct or indirect discernible evidence of weapons-related activities. In all three visits, the U.S. teams were confident about their conclusions.

The problem of plutonium separation was a central concern, yet the U.S. teams found no evidence of separation facilities or any indirect evidence—such as radioactive waste or frequency of removing fuel elements from the reactor—that would suggest secret reprocessing activities. Nevertheless, the U.S. team warned that “within 12-18 months” Israel could install a separation plant and transform Dimona from research to weapons mode.

The key finding of the 1965 report was the team’s conclusion that while Dimona presented “no near term possibility of a weapons development program,” the reactor “has excellent development and plutonium production capability that warrants continued visits at intervals not to exceed one year.”

A major question was what Israel intended to do with the irradiated fuel removed from the reactor core. Pratt told the 1965 U.S. visitors that the spent fuel would probably be returned to France for chemical processing, although he “gave the impression that no detailed consideration has yet been given to this problem.” We now know this was misleading. The Israelis never returned spent fuel to France; instead, they reprocessed the irradiated reactor core every six months.

The 1966 report and the Atomic Energy Commission’s cover letter addressed the possibility of deliberate Israeli deception and the possibility of a hidden reprocessing plant on site or another reactor elsewhere in Israel. It admitted the “bare possibility that the reactor may have been operated to produce about 3 kilograms of plutonium since the time of the last visit in January 1965.” They recommended that U.S. intelligence “maintain a constant surveillance of the entire country to determine whether such a plant or plants exists or are being built.”

A State Department Intelligence and Research (INR) report from March 9, 1967, provided explosive information. The document remains heavily redacted, but the memo by INR chief Thomas Hughes disclosed that Tel Aviv sources had reported that Israel either had or was about to complete a separation plant, the plant was located at Dimona, and that the Dimona reactor had been operating at full capacity for weapons production purposes. According to the report, the source also indicated that Israel could assemble nuclear weapons in six to eight weeks.

These allegations were dramatic. First, they fundamentally contradicted the U.S. consensus about the status of Israel’s nuclear program. Second, they suggested the existence of a full-blown deception operation at Dimona to mislead visiting U.S. teams.

Hughes doubted the source’s claim that Israel could produce a weapon in six to eight weeks but allowed the possibility that France “might be willing to test an Israeli device without attributing it to Israel or that Israel on its own might assemble and stockpile a small number of untested devices.” He recommended that the next U.S. inspection team try to resolve the veracity of the allegations and suggested “cultivating” the Israeli sources to see if they could obtain more information.

In late April 1967, six weeks after this memo, the U.S. team made a visit to Dimona; what they knew about the INR report is unknown. Their full report remains classified, yet concerns about reprocessing were high on their mind.

Notes from the last page of the April 1967 “Report of the visit to atomic energy sites in Israel.”National Security Archive

The language in the 1967 preliminary report was categorical and assured; it left no room for doubt about the possibility of deception. On the matter of reprocessing: “There is no irradiated fuel reprocessing plant in existence or under construction at NRCN [Dimona].” Accepting Israeli assertions at face value, the team affirmed that Dimona was on its way to becoming an academic and educational center for promoting science and technology. In effect, they were deceived because they did not realize the extent of the complex Israeli machinations to disguise Dimona’s inner workings.

About a month later, as the 1967 Middle East crisis reached its climax, Israel devised a contingency plan to detonate a nuclear device as a demonstration of a new capability in the event of the “most extreme scenario,” where Israel’s existence might be in grave danger. To conduct the plan, Israel secretly assembled two or three nuclear implosion devices for the first time. The assembly site was elsewhere in Israel, but the team used plutonium cores produced at Dimona.

No outsiders knew or suspected it at the time, and it became known only in 2017, 50 years after the Six-Day War, when a key player’s testimony was published posthumously.

The Dimona nuclear power plant in Israel in January 1978.Francois Lochon/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

There are still many open questions about this history: How could professional and well-trained U.S. scientists be duped for years? When exactly and how did the U.S. learn the truth? And finally, were all U.S. government bodies and officials fooled by the deception or did some sense the truth and not acknowledge it?

Israel is a unique nuclear power. While all other nuclear powers have made their status public, Israel has not. A secret 1969 deal between U.S. President Richard Nixon and Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir provided a cover. Opacity became the shield for Israel’s nuclear exceptionalism, and to this day, Israel refuses to either confirm or deny its nuclear status.

Both countries still prefer to look the other way as if these events had never happened. Ever since the secret deal was made, no U.S. president has acknowledged it or the existence of the Israeli bomb, much less put pressure on Israel to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Ironically, Iran may now be emulating its arch-enemy’s strategy from the 1960s by moving close to a nuclear weapons capability without testing. Tehran’s proximity to a nuclear device today may be similar to where Israel was in 1967—just weeks away.

While almost the whole world knows much about Iran’s production of highly enriched uranium, its progress in weaponizing it and how close Tehran actually is to an assembled device is another matter.

The newly declassified documents from the 1960s are a sobering reminder of the difficulty in making precise estimates of any country’s nuclear weapons program.

Avner Cohen is a professor in the Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies (NPTS) at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey in California. He is the author of Israel and the Bomb and The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel’s Bargain With the Bomb. X: @avnercohen123

William Burr is the director of the Nuclear Documentation Project at the National Security Archive at George Washington University.

More from Foreign Policy

-

Russian President Vladimir Putin looks on during a press conference after meeting with French President in Moscow, on February 7, 2022. The Domino Theory Is Coming for Putin

A series of setbacks for Russia is only gaining momentum.

-

The container ship Gunde Maersk sits docked at the Port of Oakland on June 24, 2024 in Oakland, California. How Denmark Can Hit Back Against Trump on Greenland

The White House is threatening a close ally with a trade war or worse—but Copenhagen has leverage that could inflict instant pain on the U.S. economy.

-

Donald Trump speaks during an event commemorating the 400th Anniversary of the First Representative Legislative Assembly in Jamestown, Virginia on July 30, 2019. This Could Be ‘Peak Trump’

His return to power has been impressive—but the hard work is about to begin.

-

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio greets employees at the State Department in Washington, DC, on January 21, 2025. The National Security Establishment Needs Working-Class Americans

President Trump has an opportunity to unleash underutilized talent in tackling dangers at home and abroad.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.