Is UBS’s ‘deal of the century’ starting to sour?

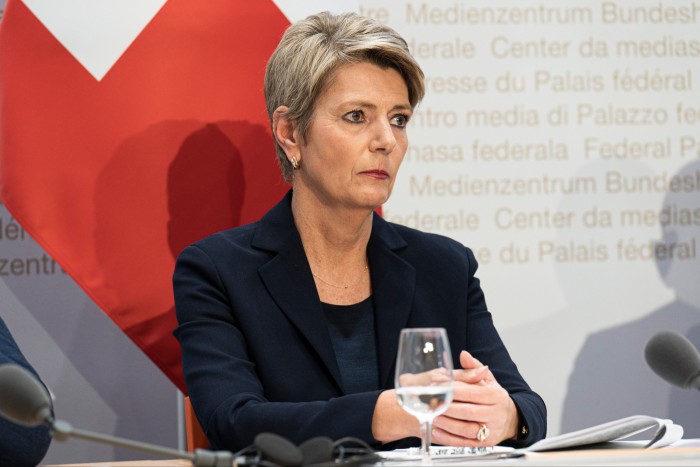

UBS’s senior leaders and Swiss finance minister Karin Keller-Sutter are barely on speaking terms. Two years after the bank stepped in to buy Credit Suisse in a state-engineered rescue, the government is preparing to impose strict new capital rules on the enlarged lender, and the politician spearheading the crucial reforms is in no mood to be conciliatory.

“There have been several contacts on the highest level between the finance ministry and UBS,” the ministry told the Financial Times. “However, these talks are not negotiations and it would be a mistake to conceive them as such.”

The pending reforms, which could result in UBS being forced to hold as much as $25bn of additional capital, have pitted Switzerland’s largest bank against the country’s political and regulatory establishment in a dispute that has become increasingly febrile.

After being handed what one Swiss politician called the “deal of the century” when it acquired Credit Suisse two years ago — generating a $29bn accounting gain in the process — UBS has found itself fighting a rearguard action. The saga has weighed on the bank’s share price and could yet force it to reconsider some of its longer-term strategic plans, according to insiders and analysts.

“What UBS can control is going well: the integration, the reducing non-core assets, the restructuring,” said Andreas Venditti, a senior bank analyst at Vontobel. “The reason the share price has suffered, and the stock has underperformed US and European peers, is the regulation uncertainty.”

At the centre of the debate is a mooted reform that would require UBS — which has significant operations in the UK and US — to back its foreign subsidiaries with 100 per cent equity, compared with 60 per cent at present. Finma, the financial regulator, and the nation’s central bank have lined up behind the proposal ahead of an overhaul of the country’s financial regulation, which is being led by Keller-Sutter.

Such a change would push UBS’s so-called core equity tier 1 ratio, a crucial measure of capital strength, from its current level of about 14 per cent of risk-weighted assets to as high as 19 per cent. This would require the lender to hold significantly more capital relative to many global peers, increasing its requirements by between $15bn and $25bn, according to analysts’ estimates.

Sergio Ermotti, UBS’s chief executive, has called the proposal “absolutely excessive”, and the bank has been lobbying strongly against it. UBS could live with a “minor adjustment”, people familiar with the matter say. The bank said it supported the government’s proposals to strengthen Swiss financial stability “in principle”, but opposed “disproportionate measures”.

Others looking on have little sympathy. “If I were the Swiss regulator, I would be doing the exact same thing,” said a senior executive at another large European bank. “UBS will need to face the music that it will have to hold more capital.”

The debate comes as public opinion in Switzerland has soured towards UBS, with politicians expressing unease about the size of the combined bank, which now has a balance sheet that is larger than the country’s economy.

Months earlier Swiss lawmakers sharply criticised Finma — under its previous leadership — for granting Credit Suisse relief from capital requirements in the years before its collapse. Now with German national Stefan Walter at the helm, the regulator and the finance ministry are aligned.

Officials argue Switzerland needs to strengthen the financial sector’s stability and reputation in the wake of Credit Suisse’s demise, and to protect against a potential future rescue of UBS, which has become much larger and far more of a too-big-to-fail risk to the country.

“UBS is already one of the best-capitalised banks globally,” the lender said in a statement to the FT.

Relations between the two sides have deteriorated in recent weeks, with the debate playing out in the media and online via leaks and threats, including a suggestion that UBS was considering relocating its headquarters. Such acrimony is an anomaly for Switzerland, where pragmatism and a conciliatory approach to negotiating traditionally prevail.

Ermotti devoted 3,600 words in an open letter to employees earlier this month, criticising the authorities for becoming the “greatest obstacle to delivering a successful outcome” for UBS and Switzerland, while Keller-Sutter hit out against the bank’s “intense” lobbying effort. “I represent the interests of taxpayers . . . UBS represents its business interests,” she recently said.

One Swiss banking executive said: “It’s just not Swiss. It’s Trumpian-style politics playing out with public arm-twisting and posturing and nobody on either side is engaging in sensible, calm discussions directly. Many in the industry are dismayed it has come to this.”

Draft legislation on the capital rules is set to go before Swiss lawmakers by June. But the finance ministry’s February decision that the reforms would be implemented via legislation rather than executive order means any changes are unlikely to come into force before 2028. The uncertainty is weighing on investors’ outlook for UBS.

The lender has missed out on an unprecedented rally in European bank shares over the past year. While the Swiss lender’s stock is still trading about 60 per cent higher than it was before agreeing the Credit Suisse acquisition, it has flatlined in the past 12 months.

Meanwhile, shares of other major lenders on the continent have soared in the past year, including UniCredit and Santander, which have jumped about 50 per cent and nearly 40 per cent respectively. The Euro Stoxx Banks index, which tracks the biggest lenders in the Eurozone, is up more than 40 per cent during that time, and by nearly 100 per cent since UBS’s acquisition of its crosstown rival in March 2023.

UBS executives view the capital debate as a “huge overhang” for the bank’s share price performance, said people familiar with the matter.

The Swiss lender remains one of Europe’s most valuable banks, trading at about 1.2 times book value. But it had hoped its acquisition of Credit Suisse would help it narrow the valuation gap between it and US peers, by allowing it to cherry pick the most attractive assets, clients and staff from its former rival’s wealth management business and investment bank.

UBS has sought to replicate Morgan Stanley’s moves made in recent years: the bank where chair Colm Kelleher spent most of his career and which also has a large wealth management operation, but trades at about two times book.

Last year, Ermotti announced a new three-year strategy that centred around boosting the wealth management business, particularly in the US and Asia. He targeted increasing invested wealth management assets from $3.8tn to more than $5tn by 2028, and attracting $100bn of net new assets a year by 2025 to achieve this.

However, there are now doubts about the feasibility of UBS’s objective to close the gap with US peers, which could rankle with the bank’s increasingly demanding shareholder base.

Johann Scholtz, an analyst at Morningstar, said aspects of UBS’s performance had underwhelmed in recent months, notably in wealth management.

“The market has been a bit disappointed with the growth in net new assets [in wealth management] over the last few quarters,” said Scholtz, adding that the targets could be more ambitious.

Scholtz said the US wealth arm continued to drag on the group’s overall profitability, and higher capital requirements would only make things worse. He said the reforms could cast doubt on the viability of its strategy of targeting the US wealth market.

“If you’re going to see higher capital requirements, you really need to take a long, hard look at whether it makes sense to have an extensive continued presence in US wealth management. It would lift the hurdle for the US business even higher and the bank’s competitive position would suffer.”

Some shareholders have firmly backed UBS — including activist investor Cevian Capital, which publicly gave its backing to the group’s leadership and strategy as recently as February.

But investors once believed UBS had the potential to align its market value with US peers, said people close to the bank. “Now they are saying: ‘It could be that UBS is becoming more like a European bank than a US peer — the jury’s out.’”

All of this — the public maelstrom over capital requirements, Ermotti’s strategy and the underwhelming performance of its wealth business in recent quarters — comes against the backdrop of UBS having to manage the complex integration of Credit Suisse. The process is entering the crucial phase of migrating more than 1mn Swiss retail clients on to UBS’s systems.

“It’s like trying to perform open heart surgery and having people come into the surgery room trying to distract you,” said one person familiar with the situation.

At the same time, the bank is building up plans to cut headcount through redundancy programmes, as well as using other levers such as natural attrition and retirements.

Executives are targeting a headcount of about 85,000 by the end of the integration process in 2026, meaning a further 25,000 positions are likely to be axed over the next 21 months. One person familiar with the matter said the bank’s attrition rate — the percentage of staff leaving each year — is below its historic norm, complicating the process.

UBS and the Swiss establishment are settling in for a long fight, with consultations and lobbying likely to drag on for three more years. Even then, the proposal could be put before the Swiss public in a national referendum.

“The shock of the collapse of Credit Suisse was so big and the public opinion of what happened so negative [that it] has created this situation,” said Vontobel’s Venditti, adding a referendum “would be a bad outcome for the bank, given the negative public opinion”.

Another banking industry insider was more blunt: “The Swiss are intelligent and informed. But even so, you could have a scenario where you have people in far-flung villages voting on something that is highly technical.”

One top 15 shareholder in UBS said the uncertainty around the capital reforms was unhelpful, but expressed hope that the two sides would find a workable solution.

“Switzerland always comes to the conclusion that the country benefits massively from having UBS domiciled and operating there, in the same way that UBS benefits massively from being in Switzerland. It is a two-sided relationship that is mutually beneficial. We believe there will be a proportionate outcome and sanity will prevail.”