The last grand strategists: what Brzezinski and Kissinger could teach Trump

Picture Muhammad Ali limbering up for his great Kinshasa “rumble in the jungle” with George Foreman. Or Björn Borg squaring off for a Wimbledon centre court final with John McEnroe. Most fittingly, ruminate on chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer ahead of his 1972 Reykjavík “match of the century” against Soviet opponent Boris Spassky.

Although it spanned decades and influenced the course of two superpowers, the rivalry between Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger, America’s great cold war strategists, merits equivalent hyphenation. Brzezinski-Kissinger was to US geopolitics what great pairing is to sport. Their core difference was over whether to sustain cold war détente — easing the strains — with America’s mortal rival or to resume ideological struggle with the USSR.

Kissinger won the battle of celebrityhood. In my view Brzezinski won their cold war dispute on points. Kissinger was wrong to presume the Soviets would be a permanent feature of the landscape. Brzezinski correctly saw the USSR’s dormant nations, including Ukraine, as its Achilles heel. Either way, their clash over how to manage the cold war mattered as much as today’s schism between those in Donald Trump’s world who laud his wish for détente with Vladimir Putin’s Russia and those who see both imposing a Munich-style disaster on Ukraine.

On the fate of Ukraine rests the future of war and peace. A key distinction from the Kissinger-Brzezinski era is that no one today can match either’s intellectual creativity, public reputation and diplomatic weight. America’s missing strategy, in other words, owes something to the absence of grand strategists.

What did they have that eludes their lesser-known heirs in today’s America? The simplistic answer is that Kissinger and Brzezinski were immigrants. Newcomers often value America’s freedoms more than its native-born and are statistically far likelier to start companies, win Nobel Prizes and indeed launch schools of thought.

Brzezinski’s rise as a Sovietologist at Harvard then Columbia in the age of America’s “cold war university” — a public-private collaboration that is the mirror image of Trump’s war on Ivy League budgets — coincided with Kissinger’s emergence as a Harvard name and bestselling diplomatic historian. Each had surpassing ambitions that shocked many of their more cloistered (and less egotistical) peers.

A richer pointer can be found in the tales of their emigration. It was no accident that a 15-year-old Heinz Kissinger arrived in America a month before Neville Chamberlain’s infamous 1938 betrayal of Czechoslovakia in Munich. A few weeks later, a 10-year-old Brzezinski caught his first glimpse of the Statue of Liberty having left Europe’s shores two days after Hitler completed his occupation of the Sudetenland.

Each had been raised in the “bloodlands” of interbellum Europe. One was a Jewish-German refugee whose extended family would be wiped out in the Holocaust; the other was the son of a Polish diplomat whose country would be razed less than a year later when the Soviets and Nazis spliced Poland in history’s ugliest vivisection.

They were marked in different ways by the harrowing fate of those they left behind. Given a choice between order and justice, Kissinger said he would always choose order. His people were liquidated amid history’s most brutal disorder. Brzezinski would have chosen justice. Wounded Polishness — a sense of amputated history — was the launch pad of his ambition.

Crucially, though, they shared a burning sense of the tragic. “As immigrants, we knew about the fragility of societies and we had an instinct for the transitoriness of human perceptions,” Kissinger told me in 2021, four years after Brzezinski died aged 89 in Virginia and two and a half years before Kissinger himself passed away in Connecticut having recently turned 100.

Kissinger was among the sources for my full biography of Brzezinski, which comes out next month. The difference between the two, in Kissinger’s view, was that Kissinger came from Germany but had not been defined by it, while Brzezinski had been defined by Poland, although it had “not set limits on what he became”.

But Kissinger wanted to stress what they had in common. Together, though with Kissinger as the pioneer, they supplanted the old Anglo-American elite. Figures such as Averell Harriman, Dean Acheson and John McCloy conducted diplomacy as a second career or part-time obligation. Kissinger and Brzezinski, on the other hand, were brash professionals who lacked the social ties of the Georgetown wise men. In Acheson’s words, the former were “present at the creation” of the US-made postwar order. Kissinger and Brzezinski grappled varyingly with the existential threat to that order.

More important, however, was their exposure to societal breakdown and the eternity of geopolitics — an experience that no Wasp could emulate. “The question is whether Americans can ever understand that we are living in a continuous experience that has no end, and that you can never segment life into different problems,” Kissinger said. “[As Europeans] we knew that we were living in a continuous history. It never comes to an end.” He might also have quoted the great American novelist William Faulkner, who said: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

The worldliness of these two modern-day viziers was also manifested in very different ways. Kissinger was seductive, a master of flattery and a maestro of the press conference. Brzezinski was better at making media enemies. His theory of the case — that the USSR was a gerontocracy in terminal decline — barely wavered. Kissinger, on the other hand, was strategically amorphous. He perfected the art of illusory action — “motion without movement”, as he called it. But he always gravitated back to his 1815 Congress of Vienna lodestar; a world in which great powers strove to be in balance. Brzezinski’s worldview was filtered through the smaller players — not just his native Poland but the myriad national groups within the USSR whose separatist inclinations he sought to awake.

Kissinger had almost as little time for Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America as Trump, although he cut those services in annual salami slices rather than in one fell swoop. Brzezinski, who spoke Russian, Polish and some German, resumed ideological warfare behind the iron curtain, which he saw as porous.

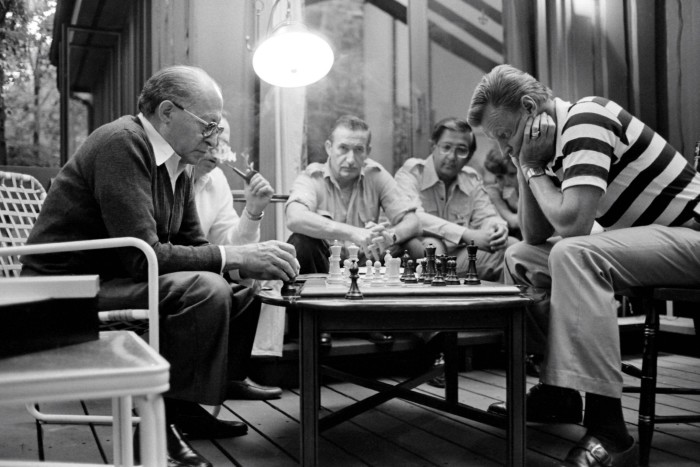

Kissinger was a juggler; Brzezinski a boxer. When the latter accused Kissinger of “acrobatics” during the Nixon years, they nearly fell out. In spite of their often irascible disputes, the Republican and Democratic sparring partners never stinted on dinners at Sans Souci, a French restaurant (since closed) near the White House. You went there to be seen. “One always learns more from ‘friendly critics’ than from uncritical friends,” Kissinger wrote to Brzezinski after one such meal in the early 1970s. It is hard to imagine such a garrulous frenemyship in today’s Washington.

The subject of tariffs never arose. Theirs was a time when the US was opening markets and laying the foundations of globalisation. On that, the two strategists absent-mindedly agreed — economics was not either’s strong suit. Today, Trump is bludgeoning that project into reverse.

Opening to China was a central feature of both Kissinger and Brzezinski’s careers. Does Trump yet have a China strategy? Notions of Trump pulling off a “reverse Kissinger” — bringing the Russians into America’s orbit, much as Kissinger exploited the Sino-Soviet split in the other direction — are fanciful. Steve Witkoff, the New York property developer, now Trump’s all-purpose envoy, has recently proved no match for Putin. A reverse Brzezinski — cutting ties with China and recognising Taiwan — is thankfully hard to foresee even with Trump’s unpredictability.

Given the secrecy with which Richard Nixon and Kissinger had to pursue America’s surprise 1972 opening to China, Beijing put a premium on personal dialogue. Urbane, silky and erudite, China’s premier Zhou Enlai was the ultimate mandarin and an ideal counterpart for Kissinger. Nixon and Mao Zedong struck the opening chords. Kissinger and Zhou sustained the duet.

Zhou’s replacement by Deng Xiaoping robbed Kissinger of his most cherished interlocutor. It was precisely the qualities that Kissinger most disliked in Deng — the Chinese premier’s blunt, sometimes uncouth, manner, and his impatience with euphemism — that most appealed to Brzezinski.

Their mutual allergy to the Soviets was the propellant of Jimmy Carter’s China move. Brzezinski was Carter’s national security adviser, as Kissinger had been to Nixon. Neither the Chinese premier’s well-used spittoon nor his chain-smoking of Lesser Panda cigarettes could check Brzezinski’s deep respect for him. Deng was “a man tiny in size but great in boldness”, Brzezinski thought. China’s 4ft 11in tall leader likewise valued Brzezinski’s directness.

Having all but gutted Kissinger’s détente, Brzezinski became known in China’s media as the “polar bear tamer” — the bear being Deng’s nickname for the USSR. Kissinger had wanted to keep an “equilateral” distance between the US, USSR and China. Under Carter, they became de facto partners.

Either way, it is hard to imagine Trump plunging into countless hours of tactical back-and-forth with China’s President Xi Jinping or Putin. Nor would Trump be likely to give his national security adviser, Mike Waltz, or secretary of state, Marco Rubio, anything close to Kissinger-Brzezinski latitude.

Deng spent his first night on American soil at a boozy dinner in Brzezinski’s Virginia family home. It was the start of the first ever US state visit by a Chinese leader. They toasted US-China normalisation with vodka presented to Brzezinski by Anatoly Dobrynin, the USSR’s ambassador in Washington. Guests were served by Brzezinski’s children. His 11-year-old daughter, Mika, spilled Russian caviar (also from Dobrynin) into Deng’s lap, and tried to clean it up with a napkin.

The next day, Nixon was controversially present at Deng’s state dinner — the disgraced president’s first return to the US capital since his Watergate exit. Brzezinski persuaded Carter that Nixon’s addition would cement China’s confidence in America’s bilateral embrace. Kissinger abruptly turned against normalisation. But his pique was fleeting. He would go on to become China’s favourite visiting American.

How would each handle today’s Russian war on Ukraine? In spite of their differences, it is a good bet that neither Brzezinski nor Kissinger would have advised Trump to offer concessions to Russia ahead of peace talks. Sweeteners are meant to be dangled not gift-wrapped in advance.

Both would have been mortified by Trump and his vice-president JD Vance’s Oval Office humiliation in February of Volodymyr Zelenskyy. As a seducer, Kissinger caught most of his flies with honey. Razor sharp and occasionally prickly, Brzezinski was closer to a Venus flytrap. Neither would have seen Zelenskyy as prey, still less in front of the cameras.

It is impossible to imagine either speaking about Putin in the manner Witkoff recently did to the Maga broadcaster Tucker Carlson. Witkoff disclosed that Putin had said he had prayed for Trump in church after last summer’s assassination attempt. The Russian leader also presented Witkoff with a flattering portrait of Trump. Putin was “enormously gracious”, said Witkoff. “It takes balls to say that,” Carlson replied. Whatever becomes of Trump’s Russia-Ukraine peacemaking ambition, Putin seems to have a better read of Trump than Trump of Putin.

Late in life, Kissinger and Brzezinski nearly swapped their Russia positions. In a 2014 op-ed for the FT, Brzezinski argued for the “Finlandisation” of Ukraine, which would make it an unallied, though pro-western, buffer state between Russia and Nato. Even more startlingly, Kissinger endorsed Ukraine’s Nato membership following Russia’s 2022 invasion. Kissinger’s U-turn can probably be attributed to his habit of keeping within the bounds of consensus, one linked to the needs of Kissinger Associates, his thriving business. Access to the White House and other chancelleries was vital to his consultancy.

Brzezinski did not run a business. He thus had no need to curb his views. He criticised every president. This included Barack Obama, whom he had endorsed for president and admired partly because of his opposition to the 2003 Iraq war. Bill Clinton, who turned first to thank Brzezinski after he signed the bill ratifying Nato’s initial expansion in 1999 that included Poland, also fell out of Brzezinski’s favour because of his alleged soft treatment of the newly elected Putin. The exception was Jimmy Carter, with whom he remained life-long friends.

Brzezinski’s diluted stance on Russia can be explained by a dose of autumnal softening, although he never lost his dark view of Putin. It took his children a while to persuade him to install a pacemaker after he had a stroke in late 2014. The prospect offended him on several levels; the device would be a reminder of his dwindling lifespan; it entailed technology to which he had an instinctive aversion; worst of all, it would upload data to a receptor that could expose him to compromise. The Russians would be able to hack into his medical information. “You know, I think Putin has enough on his plate right now to be worrying about your medical data, Dad,” said his older son, Ian Brzezinski. His middle child, Mark, later became Biden’s ambassador to Poland.

Critics of Kissinger and Brzezinski have plenty of material to play with. “Henry Kissinger, war criminal, beloved by America’s ruling class, finally dies,” was Rolling Stone’s obituary headline. Nixon’s secret bombing of Cambodia, his backing of Pakistan’s bloody suppression of the uprising in what was to become Bangladesh, the US-backed coup in Chile and wiretapping his own staff dogged Kissinger for the rest of his life. Yet he also negotiated the first nuclear arms control agreement and came close to clinching a second. Détente was no chimera. The older he got, the more Kissinger was treated as an oracle.

Brzezinski’s time in government left no blood on his hands. Carter was the only postwar president never to order soldiers into combat, although eight servicemen died in the aborted Iran hostage rescue attempt. Brzezinski did help lure the Soviets into Afghanistan in 1979, although it was obviously Leonid Brezhnev’s decision to invade. “They’ve taken the bait!” Brzezinski allegedly told an aide on hearing the news. The origins of global jihadism can partly be dated to then. But claims that Brzezinski played “godfather of al-Qaeda” are an absurd leap. The terrorist group was formed seven years after Carter left office.

Some argue that today’s conditions make it far harder for a Kissinger or a Brzezinski to emerge. In the digital age, geostrategic manoeuvring is so much more difficult to execute. Their by no means overlapping detractors say it is a good thing they lack contemporary equivalents. Yet, to paraphrase what one of Trump’s favourite movie characters, Hannibal Lecter, said of his interrogator, the world was more interesting with Kissinger and Brzezinski in it. And to edit-quote someone else, competing strategies beat no strategy.

When Brzezinski died, Kissinger was surprised how bereft he felt. The two had first met in Harvard 67 years earlier. “How central Zbig’s presence had been to my image of a world worth living in and defending hit home with an unexpected force,” Kissinger wrote to Brzezinski’s family on learning of his death. “I felt as if a sustaining pillar of the structure of the world I cared about had disappeared . . . We shared, I like to think, a cause, if not always our ambitions.”

In death, more than life, these two naturalised Americans seem to get along. As their era recedes, and as America repudiates the world it made, both figures deserve study.

Edward Luce is the FT’s national editor. His biography ‘Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Cold War Prophet’ is published next month by Bloomsbury in the UK and by Avid Reader Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, in the US. It is available for pre-order

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning