How Generations of Experts Built U.S. Power

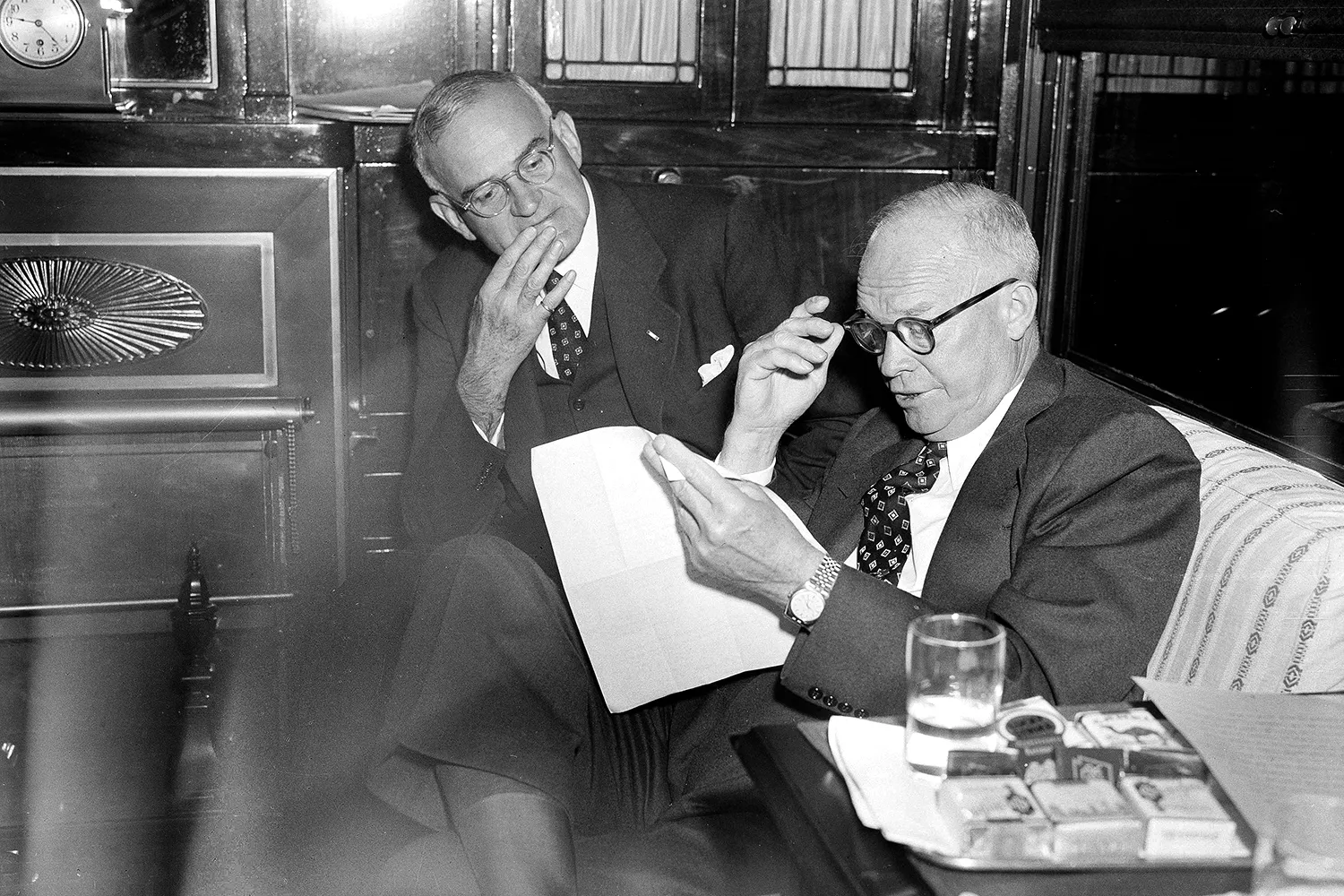

Republican presidential nominee Dwight D. Eisenhower (right) and his advisor Robert Cutler converse in a railroad car in Philadelphia on Oct. 17, 1952. Henry Griffin/Associated Press

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously wrote that war is a “mere continuation of policy by other means,” but he did not mean that war is merely politics. Clausewitz’s influential 1832 treatise, On War, meditates deeply on the vital role of training, expertise, and exceptional talent in managing the complexities of national defense. War requires technical skill, organizational acumen, historical knowledge, and strategic insights. While courage and toughness are necessary, Clausewitz writes, these qualities do not substitute for learning. War is too dangerous to be left to dilettantes and pretenders.

Since the creation of the Continental Army, Americans have always looked to expertise in managing defense. George Washington was chosen to command the revolutionary military because of his extensive experience in the British Army. His soldiers were unseasoned fighters, but he brought knowledge to his leadership; the ability to bring in knowledge, not his checkered record in battle, was one of the main reasons why he was so highly regarded by the troops.

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously wrote that war is a “mere continuation of policy by other means,” but he did not mean that war is merely politics. Clausewitz’s influential 1832 treatise, On War, meditates deeply on the vital role of training, expertise, and exceptional talent in managing the complexities of national defense. War requires technical skill, organizational acumen, historical knowledge, and strategic insights. While courage and toughness are necessary, Clausewitz writes, these qualities do not substitute for learning. War is too dangerous to be left to dilettantes and pretenders.

Since the creation of the Continental Army, Americans have always looked to expertise in managing defense. George Washington was chosen to command the revolutionary military because of his extensive experience in the British Army. His soldiers were unseasoned fighters, but he brought knowledge to his leadership; the ability to bring in knowledge, not his checkered record in battle, was one of the main reasons why he was so highly regarded by the troops.

Although he abhorred militarism, in 1802 President Thomas Jefferson created an elite military academy—the U.S. Military Academy at West Point—to prepare leaders of the highest caliber for the young country’s defense. West Point’s first superintendent, Army Maj. Jonathan Williams, emphasized the importance of learning for military leadership: “We must always bear it in mind that our officers are to be men of science, and such as will by their acquirements be entitled to the notice of learned societies.”

In 1884, the U.S. Navy went a step further, creating a postgraduate institution, the U.S. Naval War College, for “original research on all questions relating to war and the statesmanship connected with war, or the prevention of war.” Cdre. Stephen Luce, the first president of this new institution, emphasized how important education was for successful military leaders. He wanted the experienced naval commander to be a more “complete creature.” Otherwise, he warned, “[o]ur uneducated seamen will stand no chance against the trained gunners of England and France.”

U.S. War Secretary William Howard Taft hands a diploma to a graduate at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York on Feb. 14, 1908. IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

West Point and the Naval War College were the essential foundations for the monumental transformation of U.S. foreign policy after World War II, when the United States grew from a hemispheric power into the preeminent global hegemon. In 1945, U.S. soldiers occupied centers of warmaking on each continent, U.S. sailors patrolled the world’s major seas, U.S. airmen dominated the skies around the globe, and American scientists unleashed the “absolute weapon”—the atomic bomb.

The power of the United States far surpassed the training and expertise of its highest leadership. President Harry Truman had no college degree, had limited military experience in World War I, and never took a physics course in his life. His initial war secretary, Henry Stimson, had begun his career in the early 1890s, when the United States had limited international ambitions and capabilities. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who commanded the Allied victory in Europe, expected that U.S. forces would have to leave the continent soon. Even in 1945, the country had no experience with global leadership.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Truman, Stimson, Eisenhower, and many others of their generation was to invest in the creation of new national security institutions, filled to the brim with trained experts who could help manage the country’s newfound power and responsibilities. “National security” became a new term of art for the intersection of military, diplomatic, and technical preparations for modern war—and all the various efforts to prevent it.

Training and deploying new national security experts drew on the West Point and Naval War College experiences. U.S. leaders recruited talented soldiers, sailors, and airmen who returned from war to become part of new institutions formed under the National Security Act of 1947. Veterans of war with government-funded access to higher education populated the bureaucracy of the newly created Defense Department, the secretive CIA, and the Atomic Energy Commission, which managed the early atomic bombs.

Like their Army and Navy predecessors, post-World War II national security experts were charged with bringing the highest level of learning about their war-related fields into the government, advising political leaders on threats, opportunities, and strategy. Congress created the National Security Council (NSC) in the White House to bring the best government expertise to the president, vice president, and cabinet. The policy decisions would be left to the politicians—but only after they were exposed to the most serious knowledge about war and security in the nuclear age.

In 1952, Eisenhower appointed Robert Cutler as the first special assistant to the president for national security affairs, a position soon known as “national security advisor.” Few people outside Washington knew Cutler’s name, but he managed the flow of information from experts to the president and his cabinet. For Cutler and Eisenhower, the purpose of the national security process was to bring to the White House the best options for using U.S. power and treasure to promote national interests. Technical accuracy, issue expertise, and policy experience were vital for the president to make informed decisions about deploying weapons, distributing assistance, shaping alliances, and containing communist advances.

The NSC became the vital center for Washington’s Cold War policymaking. Experts informing the briefings and option papers discussed in the NSC populated government bureaucracies, universities, and think tanks, including RAND, the Brookings Institution, and many others. At its best, U.S. foreign policy funneled the knowledge of the sharpest minds into decisions, whether on European and Japanese reconstruction, the pursuit of arms control, or international economic development. Some of the most influential unelected experts in U.S. foreign policy worked as national security advisors—including McGeorge Bundy, Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Brent Scowcroft, and Condoleezza Rice.

#gallery-2 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 100%;

}

#gallery-2 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

- U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with generals, ambassadors, cabinet secretaries, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, and other officials in the dining room of the White House in Washington on March 26, 1968.

- U.S. President Barack Obama drops by a meeting that National Security Advisor James L. Jones was holding with former national security advisors in the Situation Room of the White House on March 24, 2010.

Of course, national security experts made grave mistakes, especially by supporting wars in Vietnam and Iraq. But they helped manage a relatively stable international order for more than 70 years. The U.S. national security system gave presidents good options for using military, economic, and soft power to influence the world in ways that generally served U.S. interests. The United States remained secure, managed alliances on every continent, benefited from a growing economy, and finally saw its main adversary, the Soviet Union, crumble. Experts helped prevent nuclear war and other global cataclysms. Some scholars argue that U.S. national security experts, as they worked with their counterparts abroad, helped civilize foreign policy by advocating for international law and human rights.

President Donald Trump is purging U.S. foreign policy of national security expertise, diminishing his administration’s ability to pursue the nation’s interests. He has installed loyal politicians, not policy experts, in the top national security spots. Mike Waltz is the first elected politician to become national security advisor. Secretary of State Marco Rubio was also an elected politician, as were CIA Director John Ratcliffe and Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was a second-rate TV newscaster. None of these individuals have serious expertise in national security affairs, nor do they have deep connections to the community of experts. If anything, they were chosen by Trump because they are hostile to experts.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and National Security Advisor Mike Waltz speak with reporters after they met with a Ukrainian delegation in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on March 11. SAUL LOEB/POOL/AFP/Getty Images

The lack of knowledge and competence reached an alarming low point in March, when Trump’s chief national security officials inadvertently shared detailed information about a planned U.S. military attack on Yemen via an unsecured Signal messaging channel with Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg. The information they divulged could have been used by adversaries to thwart the strikes and imperil the safety of U.S. military personnel. None of the obviously incompetent officials responsible for the mishap were fired or have resigned.

What Trump did, in early April, was fire some of the most competent experts near the top of the national security system. Apparently on the advice of a far-right 9/11 conspiracy promoter, Laura Loomer, he fired Timothy Haugh, the universally respected four-star general who led both the National Security Agency, which is responsible for signals intelligence, and U.S. Cyber Command, which is in charge of keeping the United States safe from foreign hacking and cyberterrorism. Haugh’s civilian deputy, Wendy Noble, was also removed. At the NSC, highly respected experts in technology and intelligence were also fired. Earlier, the president had replaced two other respected military leaders, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the chief of naval operations.

The apparent reason for these changes was insufficient loyalty to Trump—the accusation leveled by Loomer. But there is no evidence that any of these or the hundreds of other fired experts did anything other than follow the evidence and logic of the subjects they studied. They pursued the knowledge necessary to make effective policy, and they lost their jobs because the president and his political supporters did not like where that knowledge led. This is the equivalent of denying that vaccines work, but in the case of national security, the stakes are even higher: cyberdefenses, nuclear weapons, and the prospect of war with China, Iran, or North Korea.

U.S. Air Force Lt. Gen. Timothy Haugh prepares to testify before the Senate Armed Services Committee during his confirmation hearing as head of the National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command, in Washington on July 20, 2023. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

We must now recognize that the United States’ most powerful foreign-policy tools are managed by people who are ignorant, inexperienced, and separated from the knowledge they need to make sound decisions. If there is a serious military conflict in coming months, we can expect that the Trump administration will display incompetence and make damaging mistakes. Washington’s recent abandonment of support for Ukraine, Trump’s odd adoption of demonstrably false Kremlin talking points, and his disastrous tariff announcements are symptomatic of the haphazard, chaotic decision-making about national security that the world can expect to see for almost four more years.

Anti-expert leadership reverses the considered, prudent policymaking that characterized most of the post-World War II era. Expert knowledge helped protect the security, stability, and prosperity of the United States. Its absence will bring even more uncertainty and ill-considered actions. Without national security experts, U.S. foreign policy will be less well prepared to protect the country and its citizens.

War is about politics, Clausewitz reminds us, but it also requires an intellectual seriousness about the subject. Those who play at president, defense secretary, or general on television and social media are not prepared for the complexities of modern battlefields. Like the overconfident European aristocrats whom Clausewitz despised, they will lead their proud society to surprising defeats.

This post is part of FP’s ongoing coverage of the Trump administration. Follow along here.

Jeremi Suri holds the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a professor in the University’s Department of History and the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs.

More from Foreign Policy

-

U.S. President Donald Trump gives a thumbs-up upon arrival at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland after spending the weekend at Mar-a-Lago. How to Ruin a Country

A step-by-step guide to Donald Trump’s destruction of U.S. foreign policy.

-

Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives for a meeting with Vietnamese National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man in Hanoi on April 14. Why Beijing Is Standing Up to Trump

Chinese leaders have their pride, too.

-

Russian soldiers practice marching Why Don’t Russian Soldiers Revolt?

Astonishing death rates and brutal abuse have not kept troops from following orders.

-

An illustration shows a police officer trying to sudue a panicked mob of men. The Awful History of Tariffs and Depressions

What the 19th century teaches us about what happens next.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.