The Kleptocrat’s Sidekick

Review

The Kleptocrat’s Sidekick

In Britain, legions of professionals are happy to help shadowy elites stash their wealth.

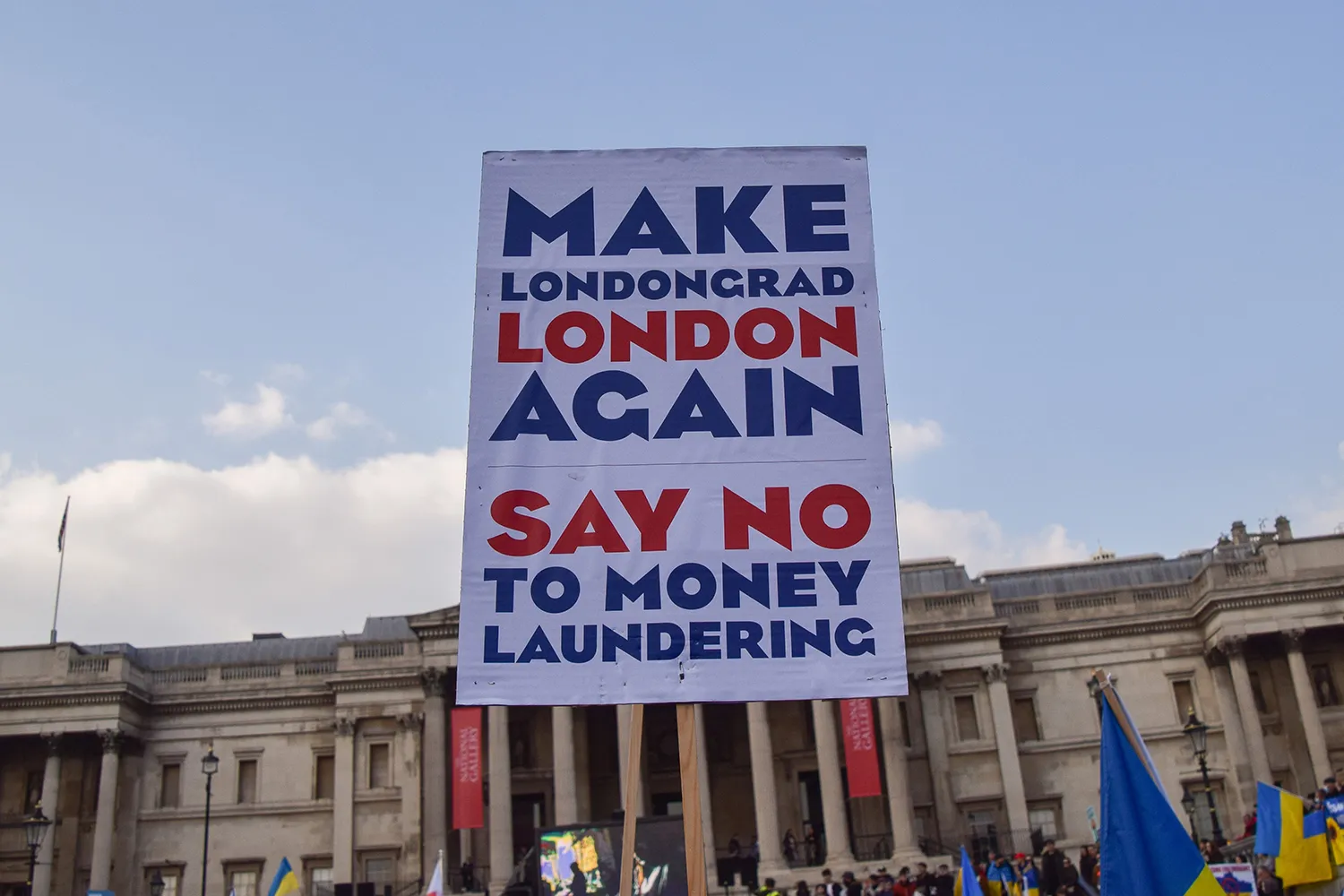

A “Make Londongrad London Again” placard is seen during a protest against Russia in London’s Trafalgar Square on March 20, 2022. Vuk Valcic/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

London, you may be aware, is the place to be if you’re a shadowy individual with piles of ill-gotten money who wishes to, ideally, shield said ill-gotten money from view.

This has been a popular topic in investigative nonfiction for some time now. In 2009, Mark Hollingsworth and Stewart Lansley published Londongrad: From Russia with Cash. In it, they describe how a “group of buccaneering Russian oligarchs made colossal fortunes after the collapse of communism—and many of them came to London to enjoy their new-found wealth.”

London, you may be aware, is the place to be if you’re a shadowy individual with piles of ill-gotten money who wishes to, ideally, shield said ill-gotten money from view.

Indulging Kleptocracy: British Service Providers, Postcommunist Elites, and the Enabling of Corruption, John Heathershaw, Tena Prelec, and Tom Mayne, Oxford University Press, 328 pp., $29.99, February 2025

This has been a popular topic in investigative nonfiction for some time now. In 2009, Mark Hollingsworth and Stewart Lansley published Londongrad: From Russia with Cash. In it, they describe how a “group of buccaneering Russian oligarchs made colossal fortunes after the collapse of communism—and many of them came to London to enjoy their new-found wealth.”

In 2020, Tom Burgis wrote Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the World, which detailed London’s path to becoming “the world’s piggy bank for blood money.” Two years later, Oliver Bullough explained in Butler to the World how the United Kingdom, despite its professed adherence to the rule of law, became a key player in frustrating global anti-corruption efforts.

Bullough is an expert on the matter, and wrote the foreword for Indulging Kleptocracy: British Service Providers, Postcommunist Elites, and the Enabling of Corruption, which came out in the United States earlier this year. Far from walking on well-trodden ground, John Heathershaw, Tena Prelec, and Tom Mayne’s book goes in for a closer look, choosing to focus on the people applying the grease to corruption’s wheels.

A cardboard cutout of Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat wearing a sign that reads “Henley & Partners Salesman of the Year” stands outside the prime minister’s office at Auberge de Castille in Valletta, Malta, on May 15, 2018. Darrin Zammit Lupi/Reuters

We all know what the world’s oldest profession is, Bullough opens, and we can assume that the pimp came second. The third is what our three academics decided to study: namely, “the sidekick, the minion, the crony, and the enabler who is prepared to hold a victim’s arms back while the pimp punches them.” These roles may come with “little glory,” but they can be deeply lucrative.

Crucially, those who have chosen to go down that road to get rich quietly can remain hidden in the shadows. They may never reach the levels of wealth of their kleptocratic and oligarchic overlords, but they can go about their lives with little scrutiny and accountability.

After all, Bullough writes, “We talk about mafia dons, but not about their consigliere; we talk about corporate barons, but not about their lawyers; we talk about the grandly corrupt, but not about the people who manage their money.” Indulging Kleptocracy seeks to change that.

The authors’ chosen frame of reference is an interesting one. The book could have begun with, say, the fall of the Soviet Union, but it instead starts much earlier, in the 16th century, as a certain Martin Luther hammers some theses to the door of a cathedral. The Reformation was partly caused by pushback to the Catholic Church’s increasing reliance on indulgences, which essentially allowed sinners to pay their way into heaven. Anything you’d done on this earthly realm could be swiftly forgotten with the right investments or charitable contributions.

Similarly, modern indulgences seek to “enrich the enablers, assuage the corrupt, and muddy the waters between right and wrong, truth and falsehood,” the authors write. Essentially, in exchange for some money, today’s wrong’uns can receive social status in Western democracies. These indulgences are granted by estate agents, lawyers, accountants, and wealth managers, among other professionals. What these people have in common is that they “facilitate transactions between two or more parties, at least one of whom has a source of wealth which is illicit.”

To study these enablers, the authors outline the different professional sectors that are “working to transform the world from one dominated by sovereign nation states … to one where public-private networks of elites dominate.” According to them, the nine ways that kleptocrats and their cronies do this are by hiding money, listing companies, selling rights, purchasing properties, explaining wealth, selling status, making friends, tracking enemies, and silencing critics.

Were kleptocrats to succeed at all of these, they would be living the dream—siphoning millions away from their country, only to be welcomed by the West with open arms and lead a life of largesse in a prosperous democracy, without having to worry about how to safeguard their wealth at home.

In practice, it is not easy for kleptocrats to tick all those boxes, but there are legions of professionals in Britain who are happy to help. Though the book can be quite achingly academic at times, especially for more casual readers, the examples it sets out are often hair-raising.

Take Henley & Partners, a U.K. company self-styled as the “global leader in residence and citizenship by investment.” Between 2006 and 2021, Henley, which now operates in more than 40 countries, helped the government of former British colony St. Kitts and Nevis issue up to 50,000 passports—more than the country’s recorded population. Between 2013 and 2020, the company ran a similar scheme with Malta, which helped 851 Russians seeking citizenship. Henley performed due diligence checks on applicants but, crucially, was also paid a commission for every individual they put forward. In Cyprus, Henley helped Jho Low, the alleged mastermind of the 1MBD fraud in Malaysia, apply for citizenship. (Low also had a passport from St. Kitts and Nevis at the time.)

A man holds a placard at an anti-kleptocracy rally in Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, near Kuala Lumpur, on Oct. 14, 2017. Lai Seng Sin/Reuters

The company has denied that its programs have a “systemic problem” or that they are used for “nefarious purposes.” As Henley sees it, it is a private actor, and whatever states end up doing is ultimately the purview of government authorities.

Still, as the authors argue, it is important to track and understand companies such as Henley because they are “not merely responding to a ‘need’ that is out there … they are creating new demand in a market dominated by wealthy individuals from kleptocratic states.”

Indulging Kleptocracy makes it clear that not all enablers are obvious or conscious ones. Still, the most amusing quotes in the book are from the people gleefully outing themselves as willing instead of gullible. Estate agent Benson Beard, for one, provides some light if acidic entertainment by telling a “client” (in fact an undercover anti-corruption campaigner filming a Channel 4 documentary), “Don’t talk to me about how [the money] comes here. … We have certain regulations within our industry where I don’t need to know where things come from.”

This quote offers a glimpse into the mindset of enablers and hints at why they have proliferated in Britain. One part of the answer lies in historical coincidence, whereby the Soviet Union was dismantled, with capital divided up between lucky elites, at the same time as the City of London continued to deregulate further and further as a way to rebuild an economy that could no longer rely on industrial production. Essentially, the British state found itself in need of money and amenable to turning a blind eye to where it came from, just as Slavic and Central Asian countries were suddenly headed by people with piles of money and no stable place to guard their wealth.

On top of this, Britain still has close links to former dependencies from the colonial era, whose legal systems are often similar to those created in London. This has allowed capital to move relatively easily between the country and various corners of the world.

Many kleptocrats also know how to make the most of U.K. libel laws, which have “long been concerned with protecting [reputation] as a thing of value.” In Britain, claimants do not have to prove that a statement published about them is factually incorrect, but merely that it is defamatory and “may cause serious harm to reputation.” This threshold is markedly lower than in other jurisdictions and has led to journalistic self-censorship in reporting on kleptocrats.

The authors are quick to point out that, though slow moving, the British state has been trying to close loopholes and monitor potential corruption more closely. It just can’t do it as fast as Britain-based enablers manage to open others and circumvent laws in ever-imaginative ways. “The state is present at least by its absence in every indulgence we have explored,” the authors write in the conclusion. “It no longer appears to effectively regulate the market. Therefore, it is the rationale of the market—competition for private goods—which triumphs over collective national action and the public good.”

Another issue lies with the very nature of kleptocracy. As the book notes repeatedly, the spouses and relatives of post-Soviet rulers often gain immense wealth through means that do not exist in bona fide democracies, from ownership of state-backed companies to suspiciously well-timed purchases of shares. Consequently, it can be tough to establish that the money was obtained “illegally” back home.

This is why, the authors argue in the end, kleptocracy ought to be treated as “serious and organized crime.” Just as Italy changed its laws in the 1980s so it could efficiently prosecute the mafia, Britain should “assume that individuals linked with listed kleptocratic regimes benefited from this association, thus presuming that some of their assets were the proceeds of crime.” This, in turn, would make it easier to find, fine, and prosecute their enablers on British soil, who would no longer be able to play dumb and pretend that they thought everything was in order.

A superyacht owned by a Russian businessman is detained in London on April 1, 2022, as part of the U.K. government’s sanctions against Russia for its ongoing war in Ukraine. The ship was registered to a company based in St. Kitts and Nevis and carried Maltese flags to hide its origins. National Crime Agency/Cover Imag via Reuters Connect

How optimistic are the authors that things will change? Eh. Although they acknowledge that successive British governments have at least pretended to care about the threats of corruption and dirty cash flooding London’s market, they have all been slow to act, perhaps because the money is actually needed.

Though few countries truly thrived in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, Britain’s economic growth has been slower than much of Europe’s since then, and leaving the European Union did not lead to the sunlit uplands once promised by Brexiteers. The years of Tory political chaos may now be over, but the relatively new Labour government is struggling to get the economy up and running again, even as the country returned to growth in February.

“[T]o indulge no more may be too big an ask,” the authors conclude, diplomatically. “Just to indulge a little less would be a victory.”

These aren’t exactly fighting words, but they are realistic ones. As the book mentions several times, the mood in the West has changed since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and suspiciously wealthy Russians with unclear links to the Kremlin are no longer as tolerated in polite society. It’s too early to tell how war will affect Europe in the long run, but we can only hope that it will lead to a broader reevaluation of Europe’s links with kleptocrats.

After all, enablers will always be around. And as the authors write, they’re likely to “exist in a moral and political universe where what might be identified as the enabling of kleptocracy is constituted as legitimate conduct.” These gray areas are where enablers thrive, and building a more Manichean world may be the only way to put an end to their actions. At the very least, it would stop all these British enablers from arguing “no, not me, guv.”

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Marie Le Conte is a freelance political journalist based in London. Her book, Haven’t You Heard? Gossip, Politics and Power, is out now. X: @youngvulgarian

More from Foreign Policy

-

U.S. President Donald Trump gives a thumbs-up upon arrival at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland after spending the weekend at Mar-a-Lago. How to Ruin a Country

A step-by-step guide to Donald Trump’s destruction of U.S. foreign policy.

-

Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives for a meeting with Vietnamese National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man in Hanoi on April 14. Why Beijing Is Standing Up to Trump

Chinese leaders have their pride, too.

-

Russian soldiers practice marching Why Don’t Russian Soldiers Revolt?

Astonishing death rates and brutal abuse have not kept troops from following orders.

-

An illustration shows a police officer trying to sudue a panicked mob of men. The Awful History of Tariffs and Depressions

What the 19th century teaches us about what happens next.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.