US thrift stores bank on windfall from Trump’s tariffs

US thrift stores are betting that the pain conventional retailers are expected to endure from Donald Trump’s tariffs will be their gain.

Many large retailers are bracing themselves for turbulent times as the US president’s levies sharply increase the cost of importing goods, some of which will almost certainly be passed on to consumers. But second-hand sellers are hoping that customers will flock to their stores in search of bargains.

“Resale is a rare industry that benefits from the administration’s global tariffs,” said Alon Rotem, chief strategy officer at online consignment and thrift store ThredUp. “Everything we sell comes from the closets of Americans, so everything we sell is immune.”

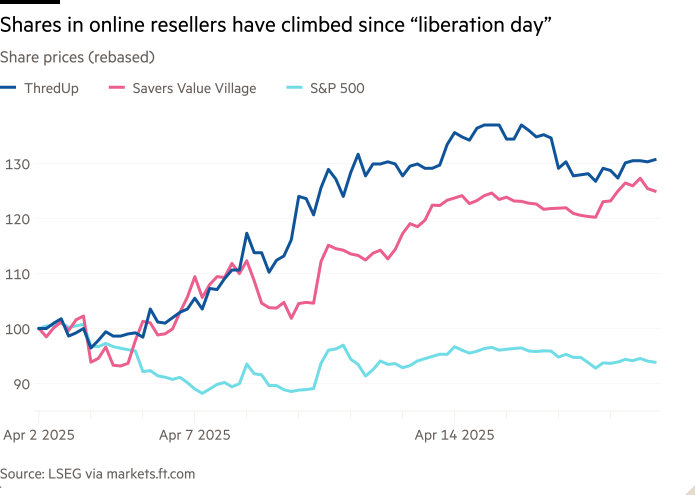

Shares of ThredUp and Savers Value Village — the two largest publicly traded thrift stores in the US — have climbed 31 per cent and 22 per cent, respectively, since Trump announced his “liberation day” tariffs on April 2. The S&P retail select index is down 7 per cent in that time, according to FactSet data.

Even after Trump announced a 90-day pause on his “reciprocal tariffs”, the remaining 10 per cent blanket levy on most imports — as well as a combined 145 per cent duty on goods from China — is expected to raise consumer prices by 2.9 per cent, costing the average household $4,700 a year, according to the Yale Budget Lab.

Analysts warned that costs for clothing and toys, in particular, could increase sharply in the coming months due to the US fashion and merchandise industry’s heavy reliance on imports from China.

Resale, however, allows companies to “sidestep tariffs,” said Simeon Siegel, a retail analyst at BMO Capital Markets. He added that the second-hand market, already popular among younger consumers, would be “doubly attractive” in the event of a recession, as more prospective buyers begin to hunt for discounts.

“If tariffs meaningfully affect the availability or price of certain goods like apparel, cars and electronics, we expect to see buyer activity spike in those categories,” said Ken Murphy, chief innovation officer at OfferUp, a peer-to-peer online resale marketplace.

Adele Meyer, executive director of NARTS: The Association of Resale Professionals, a trade group, said she was “cautiously optimistic” that tariffs would boost the second-hand industry because resale “always flourishes during any kind of economic downturn”.

But some analysts warned that second-hand sellers were not necessarily immune to a supply shock, even if their goods came from within the US. In a climate of increased uncertainty and rising fears of unemployment, consumers might decide to buy less in the first place, or opt to hold on to their existing items for longer, leaving resellers with a smaller pool — and potentially worse quality — of inventory.

“You have to fill up these resale suppliers with items that people buy at regular stores,” said Shawn Carter, an associate professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “That’s why the best environment for resale is also the best environment for regular sale.”

OfferUp’s Murphy insisted, however, that people were more likely to supplement their income by “turning unused items into cash” in an economic downturn. He said that demand, not supply, was the key variable for most resale platforms but shrugged off fears of a consumer pullback in the US, adding that OfferUp had historically “seen demand grow when supply chains are affected”.

But Savers Value Village, which operates for-profit thrift stores across North America and Australia, was less bullish on demand outside of the US. Mark Walsh, the chain’s chief executive, warned in an earnings call in February that “the tariff issue certainly clouds the picture” for demand in Canada, which makes up more than a third of its revenues.

Nevertheless, Trump’s aggressive economic policies could be “a shot in the arm for what was already growing momentum” within the US resale market, according to Dylan Carden, an analyst at William Blair.

The US second-hand market was worth an estimated $50bn in 2024, up 30 per cent from 2023, according to figures compiled by Capital One.

The market’s growth has been driven primarily by a decline in the stigma attached to buying used goods, particularly among sustainability-conscious young people, rather than price dynamics, said Carden. He noted, however, that renewed inflationary pressures could broaden the acceptance of second-hand clothing and attract older and wealthier consumers to the market.

A jump in inflation expectations may also enable resellers to increase prices, even if their own supply costs were unaffected, he added, although pricing power may be more restricted in the event of a recession.

ThredUp chief executive James Reinhart said in an earnings call in March that rising prices for new goods, particularly from Chinese ecommerce groups Temu and Shein, could provide “some modest tailwind” for resale goods.