Trump discovers the US is no longer indispensable

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

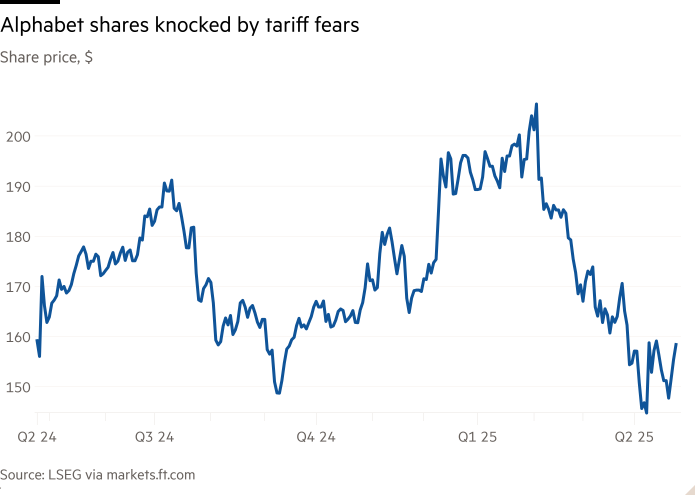

Say what you like about Scott Bessent, but the Treasury secretary’s insistence on claiming logic in every tergiversation of Donald Trump’s haphazard tariff policy is providing much amusement abroad. Bessent and other administration officials are now beetling around the world desperately trying to sign dozens of trade deals while fractious financial markets metaphorically hold a gun to their heads, and we’re asked to believe it is all a cunning plan.

Obviously, Trump’s strategy is terrible: it’s not even clear what he wants. But a less inept administration would also be struggling. Over the decades, the US’s leverage to remake the global trading system — capital flows, advanced technology and access to its vast consumer market — has weakened relative to China. Barack Obama used to call the US the “indispensable nation”. In trade and tech terms that is increasingly untrue.

During the post-second world war Marshall Plan, the US created a largely Atlanticist political economy in western Europe. It offered not just financial Marshall Aid but also advanced technology, and access to its growing consumer market.

Those advantages have dissipated. US aid budgets have massively shrunk relative to China’s, and the so-called Department of Government Efficiency has more or less closed down their last vestiges in the US Agency for International Development.

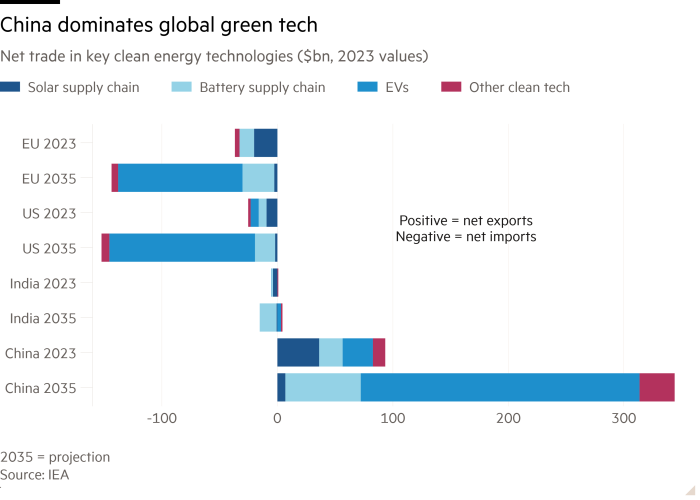

The US, particularly under Joe Biden, worked hard to deprive China of advanced technology, especially semiconductors. But the failure to match Chinese official and corporate investment, while sending the wrong signals to US industry, mean it’s well behind in much of green tech. If a country wants to adopt solar or wind power or replace internal combustion engines with electric vehicles, including batteries, it will generally get the heavily subsidised kit from China.

The Rhodium Group consultancy estimates that China’s share of global exports in solar cells and modules was 53.5 per cent in 2023, up from 35.5 per cent 10 years previously, and had risen above 50 per cent for lithium-ion batteries and semi-finished EVs.

The US, using subsidies and protective tariffs on imports, has attempted to build up its own battery, EV and solar production for the domestic market. This week, a Biden initiative came to fruition in the announcement of mesospheric tariffs of up to 3,521 per cent on solar cells from south-east Asian countries. This may be politically necessary to keep solar power alive in the US, but it will never make it a competitive exporter.

Similarly, on EVs the EU is trying to integrate cutting-edge Chinese production into its domestic market. But the US, its indigenous car industry skewed by trade protection towards giant gas-guzzling pick-up trucks that no other country wants, is creating a low-tech, high-priced EV sector that cannot compete overseas.

If it can’t offer technology to secure trade deals, surely the US still has its domestic market as an incentive? Here it retains an advantage over China, which continues to follow an export-oriented growth model. The OECD told me that in 2019, the latest pre-Covid year for which they can calculate this data, the US share of total global goods imports was 15.4 per cent, but its share of final demand (which takes account of the value added at each stage of production) was 17.5 per cent, well above China’s 9.7 per cent and even the EU’s 11.3 per cent.

The US has long used market access as bait for trading partners to cut tariffs, adopt US rules on intellectual property rights and so forth. Probably the last hurrah for this tactic was the painstakingly created Trans-Pacific Partnership, signed by 12 Asia-Pacific countries in 2016 and designed to encircle China with US-oriented economies.

But Congress held the agreement up before Trump pulled the US out altogether in 2017. The spurned countries went ahead and turned the TPP into the “comprehensive and progressive” CPTPP without the US, excising IP provisions that had been included at Washington’s insistence.

Since then the prospects for using the US market for leverage have shrunk, not just because of the secular decline in America’s share of the global economy but because of the toxicity of trade agreements in Washington. The Biden administration attempted to restore US influence in the Asia-Pacific with the “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity”. But that merely created bemusement in the region by attempting to coax partner countries to adopt US labour standards and other rules without offering export markets in return.

Trump’s idea is to threaten to take market access away with high tariffs and then restore it in return for trade concessions. It’s all stick and no carrot. The credibility of his threat to impose permanently high import duties is subject to the whim of the financial markets, and his trustworthiness in keeping those taxes low following a deal exceedingly suspect.

In the global game of trade poker, Trump inherited a weakening hand and is playing it extremely badly. Bessent and his other officials are in a precarious position. The US does not have the aid, the technology or the market access to exert control over global trade the way it once did, and Trump’s erratic behaviour is rapidly increasing the probability that it never will.