Why Trump can’t dislodge Apple from China

The last time a smartphone factory opened in the US, it closed within a year.

In 2013, Motorola announced it wanted to challenge the conventional wisdom that manufacturing in the US was too expensive. But 12 months later, the facility in Fort Worth, Texas, was shuttered because of disappointing sales and high costs.

If Donald Trump has his way, Apple will be the next tech company to test the theory. The Trump administration wants the smartphone giant to have the iPhone manufactured in America instead of China, where most of them are currently made.

“Remember the army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little screws to make iPhones?” commerce secretary Howard Lutnick said in early April. “That kind of thing is going to come to America.”

Supply chain experts believe that the Trump project would face the same problems as Motorola — indeed, some predict an iPhone could cost as much as $3,500 if fully assembled in the US.

But the reason it is so hard to shift Apple’s manufacturing to America is not solely down to the armies of workers that Lutnick referenced. The bigger issue is moving the sophisticated global supply chains built up over decades that sustain Apple’s operations in China.

“In the beginning it was about low labour costs — companies went to China because it was cheap,” says Andy Tsay, professor of information systems at Santa Clara University’s Leavey Business School. “But they stayed in China, and now they are stuck with China for better, or for worse. China is fast, flexible and world class, so it’s about much more than low labour costs now.”

Apple is planning to scale back in China but the main beneficiary will be India, where they have been developing an alternative supply chain for nearly a decade and now plan to assemble all US-sold iPhones.

A look inside the world’s most popular smartphone neatly illustrates how complex Apple’s supply chain has become — and why analysts have dismissed Trump’s vision as unrealistic.

Apple’s global supply chain is a textbook example of the elaborate networks which now dominate the global economy — and which will not be easily dislodged by tariffs.

Twenty years ago China’s main attraction for tech companies such as Apple might have been the endless supplies of cheap labour, which is still a relative advantage over the US.

But today’s iPhone supply chain utilises specific expertise for individual components built up in almost a dozen countries in Asia, which is then anchored around clusters of suppliers in China.

Experts say uprooting this mixture of organisation, scale and skills would be impractical within the span of Trump’s presidency.

Apple is “highly unlikely to move iPhone assembly to the US”, according to a report shared with the FT by research company TechInsights. “The smartphone supply chain is deeply entrenched in China, supported by skilled engineers and vast numbers of assembly workers.”

Apple ships more than 230mn iPhones each year — the equivalent of producing 438 every minute.

The company’s ability to produce at scale while squeezing costs means it earns about $400 — approximately 36 per cent net margin — on each iPhone 16 Pro (256GB). TechInisights estimates that final assembly and testing costs just $10; batteries $4; the display and touchscreen $38.

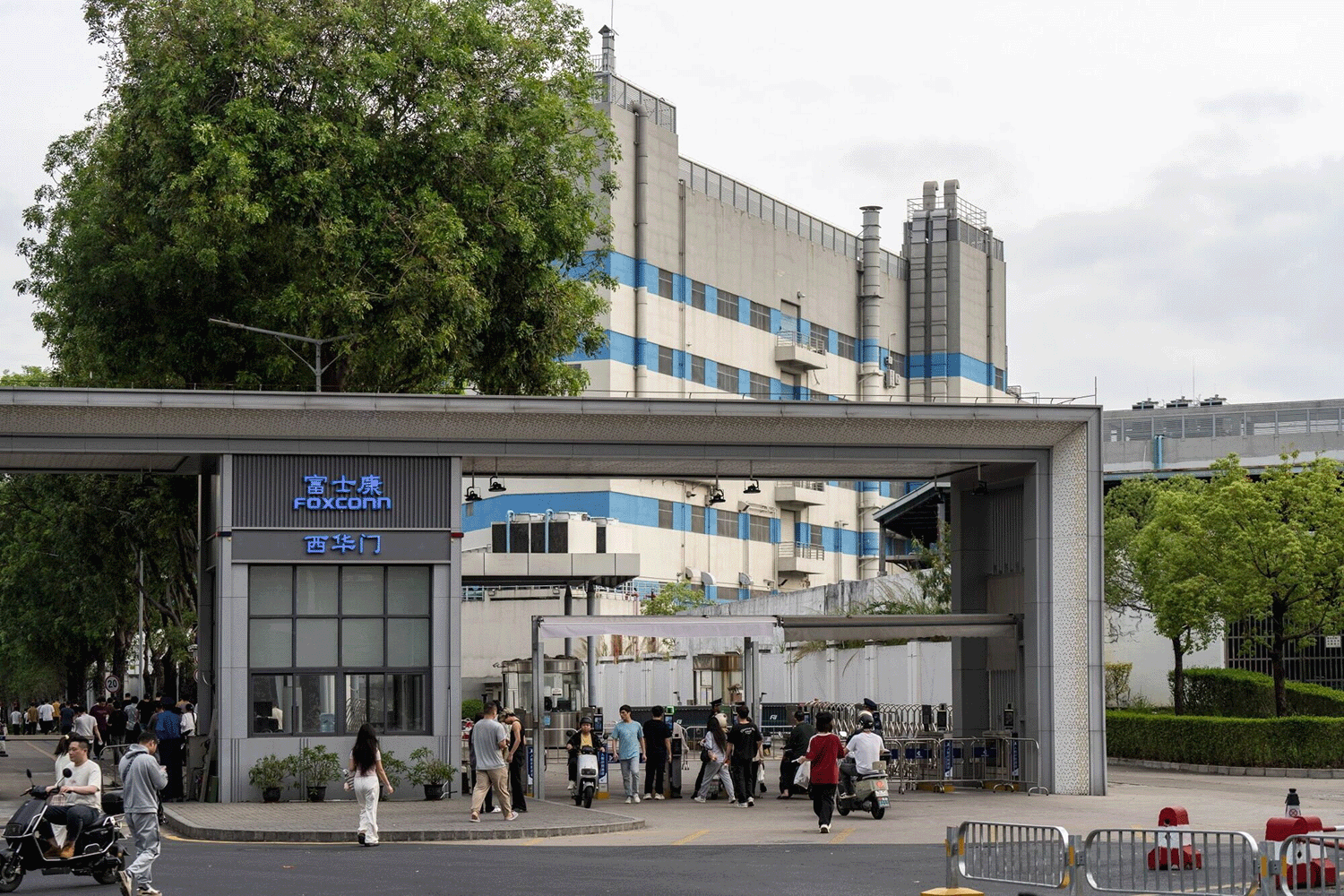

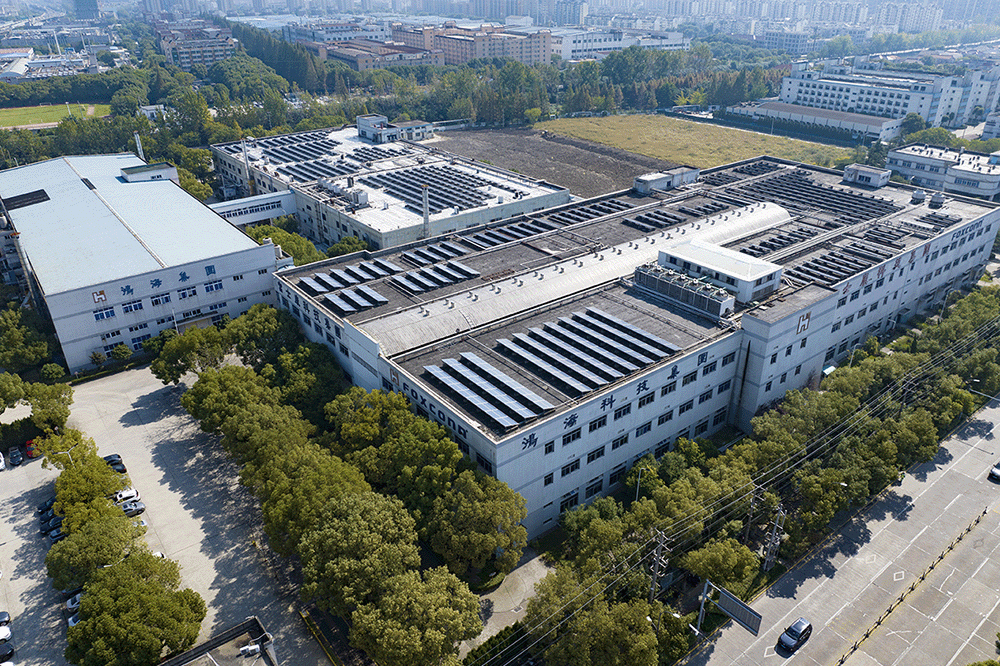

Crucial to this intricate supply chain are companies providing electronics manufacturing services, like Taiwan’s Foxconn, which assemble the majority of iPhones sold globally. Over time, Foxconn has expanded and moved production lines according to Apple’s needs: first in a factory complex in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, then diversifying to dozens of other locations in China, further into south-east Asia and now to India.

In 2010, with subsidies, tax breaks and other perks, it cost Foxconn $1.5bn to build the iPhone city in Zhengzhou that produces about 50 per cent of the world’s iPhones, says Erik Woodring at Morgan Stanley. “That’s just the cost of setting up the facility, not to run it — and at peak it has 350,000 employed there.”

But Foxconn and smaller assembly partners like Taiwan’s Pegatron and China’s Luxshare only integrate components made by hundreds of other companies. Everything from camera lenses and coatings to the various printed circuit boards and substrates that hold the iPhone together are manufactured all over China and south-east Asia.

The bulk of iPhones (around 85 per cent) are still assembled in China, with the rest made in India.

Apple’s production facilities

Just 30 of the 187 suppliers used by Apple have no presence in China

Graphic: Map showing locations of Apple’s suppliers. Most are in China, especially Jiangsu and Guangdong. Other key sites include Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand, and Japan. A bar chart also ranks Apple suppliers by country. China leads, followed by Japan, the US and South Korea.

The close proximity of suppliers and manufacturers is crucial to Apple’s productivity. “There are a lot of advantages to co-locating the activities in the supply chain, in terms of speed and quality of communication and innovation in the product and process design,” says Tsay, the professor at Santa Clara’s Leavey School of Business.

“It means that you can get deliveries very quickly, and you can communicate with your supplier very easily. And when you put an ocean between the customer, in this case Apple, and the component supplier, there is a disadvantage,” he adds.

This electronic ecosystem is why moving assembly to the US “introduces inefficiencies,” according to Wamsi Mohan at Bank of America. “If everything is not made close by, it gets complicated.”

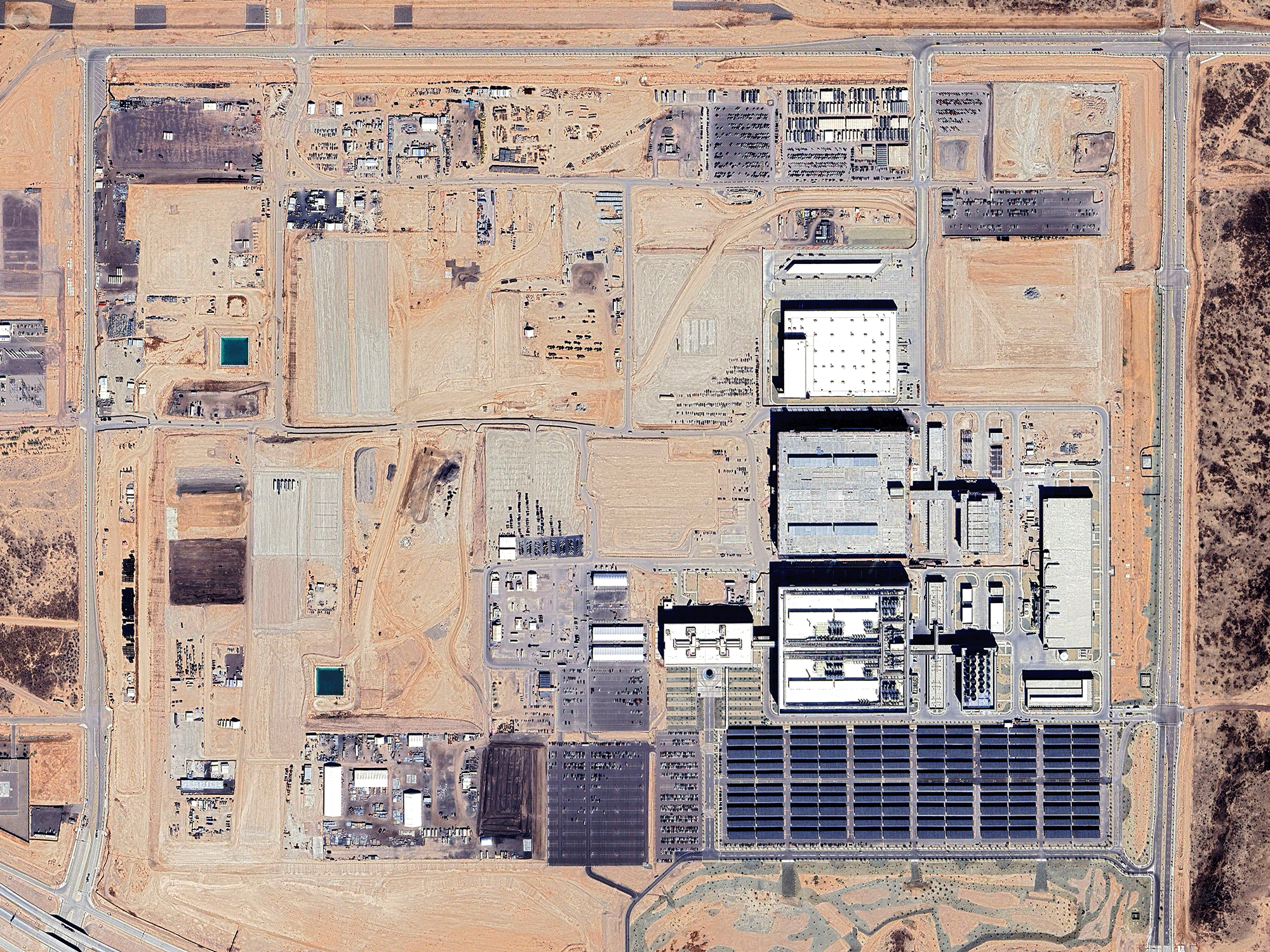

And while Apple may be able to find alternative manufacturers for some iPhone components, some are sole-sourced. Taiwan’s TSMC, the world’s largest chipmaker, supplies the main processor. Although the company says mass production began in Arizona in January, experts say there is no replacement for the chips produced in Taiwan and South Korea.

Shifting production to the US would therefore require years if not decades of coordinated investment in automation, tools, infrastructure and training. Incentivising foreign component manufacturers to build facilities in the US would also be a challenge.

“If you’re a Chinese supplier making a certain kind of component that can also be used in a Huawei or a Xiaomi phone, you’ve got leverage,” Mohan says. “The incentive to separate these factories is low, because you are getting scale and efficiency in China that you wouldn’t get if Apple was your sole supplier.”

Policy uncertainty is another problem, according to Tsay. “The American system as it stands, where everything can completely flip-flop every four years, is not conducive to business investment. When people and companies make investments, they need to have a longer horizon than that.”

Mark Randall was senior vice president at Motorola when it was owned by Google and looking to build its US smartphone factory. The idea was not impossible, he says, but “I just knew it was going to be incredibly hard.”

The US labour costs required to transform raw materials into finished goods are “significantly higher” than elsewhere, he says. The US, for example, has a shortage of mechanical tooling engineers. For a massive shift of electronics manufacturing to the US, “we are talking about needing tens of thousands of them.”

Tariffs create a “nightmare” when modelling the costs of a new plant, Randall adds. “This is why most companies don’t make short-term, knee-jerk reactions to the sort of changes that we are seeing today. You’ve got to be super strategic and know where you are going in the long term.”

Made in the USA?

A deeper look at the supply chain for three parts in the latest iPhone models illustrates the complexities of moving manufacturing to the US, in an industry that requires years to make even incremental shifts.

The one component in the touchscreen currently made in America is the cover, produced by Apple’s long-standing glassmaker Corning in Kentucky, though the company also has facilities in China and India.

But the OLED display that helps preserve battery life and an integrated multi-touch layer that enables on-screen interaction are mostly produced by Samsung in South Korea.

The core electronic parts that make the screen functional are combined with the display unit at production facilities in China, before this component is transported to a Foxconn plant to be combined with the rest of the iPhone.

The metal frame neatly captures the challenge of removing China from Apple’s supply chain. For most models, the casing is cut and shaped from a block of aluminium using high-precision computer numerical control (CNC) machines.

Wayne Lam, an analyst at TechInsights, says the process relies on an “army” of these machines, which Apple’s vendors in China have spent years amassing and which cannot currently be reproduced elsewhere. “If Apple were to onshore iPhone production, there wouldn’t be enough CNC machines they can purchase to meet the scale of the China ecosystem,” he says.

Lam adds: “This is a specialised skill that is next to impossible to replicate outside of China.”

Even the iPhone’s simplest component — its miniature screws — are complex. They are made from different materials depending on their role, and have a number of heads: philips, flat, tri-tip and pentalobe, among others.

But it is the screwing in process that sums up the challenges the company would face if iPhone production was moved to the US. Apple’s design, different from many other smartphone brands, does not use glue to attach the frame, and analysts say that it is currently more cost-effective for Foxconn to hire people to do the screwing than to invest in robotic solutions.

Graphic: An infographic showing three crucial components of an iPhone — the frame, the touchscreen and a pile of tiny screws. Arrows connect each of the components to their location in a teardown image showing the phone’s multiple parts.

With a US workforce likely to be unwilling to do such repetitive tasks at a salary that would sustain Apple’s profit margins, an American manufacturing process would require automation — the technology for which has yet to be developed.

“We have to imagine what that facility [in the US] would look like,” says Tsay. “It’s not going to be a 300,000-person facility with dormitories and gymnasiums like they have in China. It wouldn’t be the small city factory town, because the amount of human labour versus automation you use in a facility is a function of the relative cost of those two.”

The tech industry’s reliance on rare earth elements is a further complication for Apple. Lanthanum, for example, is a rare-earth metal used in the iPhone’s battery to extend its life, as well as in its screen to enhance colours. Dysprosium is also used in the iPhone’s colour screen as well as its vibration function.

The majority of such materials, essential for chips and batteries, are mined and processed by China. According to a US Geological Survey report, the US relies on China for 70 per cent of the rare earth compounds and metals it imports. Companies, including Apple, source directly from there.

This gives China leverage, with the country already placing export restrictions on a range of rare earths in response to Trump’s tariffs.

China alternatives

Under Tim Cook’s leadership, Apple has been building its supply chain resilience by finding alternative sources and routes for key components. As the company attempts to navigate the US administration’s escalating trade war with Beijing, analysts say Apple is likely to continue shifting manufacturing away from China to countries like India, Vietnam, and Brazil.

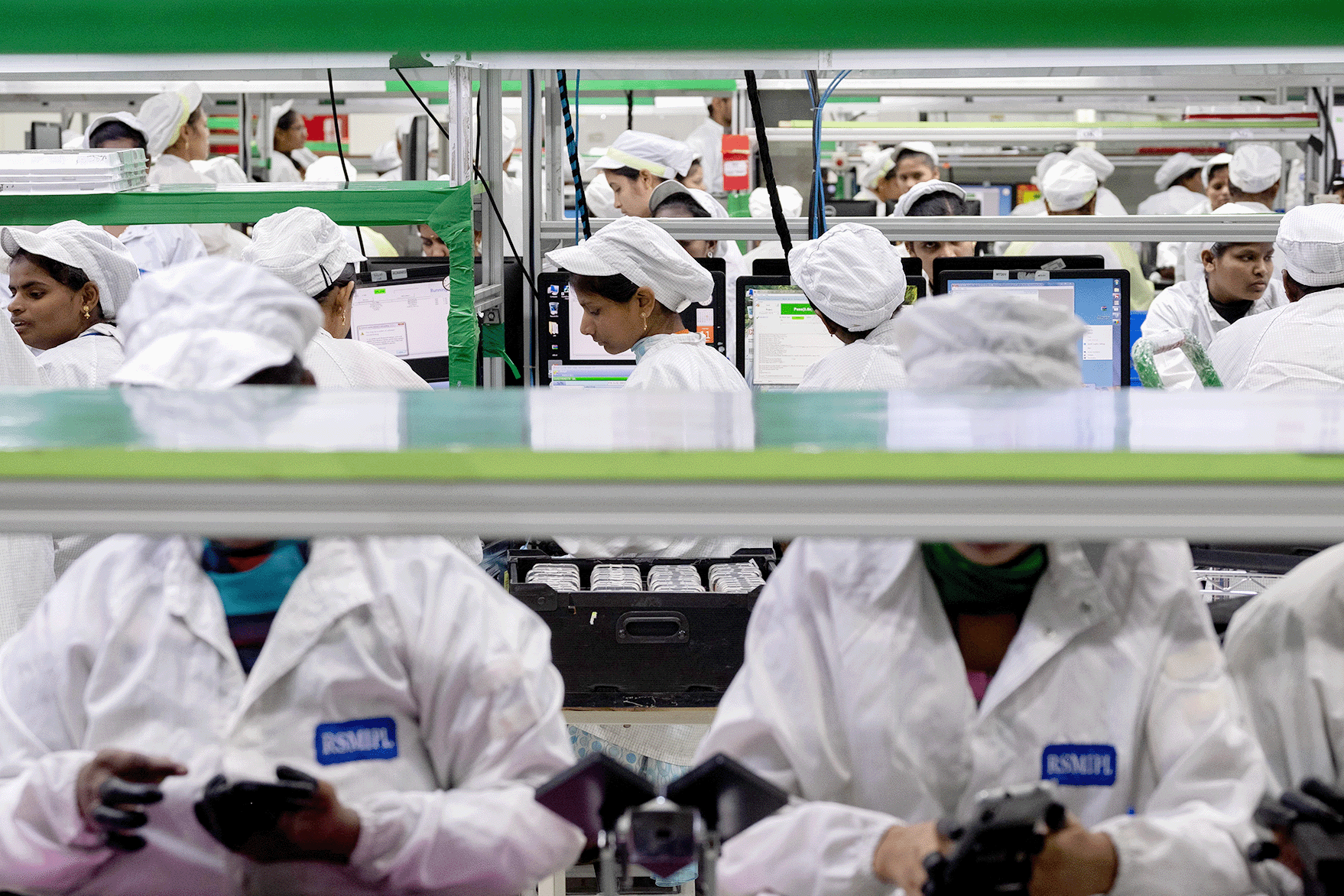

Apple has a deepening relationship with India, and plans to shift the assembly of all US-sold iPhones to the country as soon as next year, which would mean doubling the nation’s smartphone output.

“If you look at Apple’s manufacturing strategy for iPhones, it has mostly been countries where they get benefits on manufacturing: geographical advantage, government incentives and costs, and where they have good domestic demand,” says Neil Shah, a Mumbai-based analyst and co-founder of Counterpoint Research.

India not only offers government support and lower costs than China, it also has English-speaking software engineers and a big pool of consumers, he says. “India is the second-largest smartphone market in the world, and it could potentially be the largest.”

About 16 per cent of the iPhones made globally for Apple last year were assembled in India, Shah estimates, and the proportion will reach 20 per cent this year. “All the stars are aligned for India to be the alternate destination to China,” Shah adds.

When India started manufacturing iPhones in 2017, partially built kits were sent to the country to be put together — “like IKEA furniture”, Shah says.

The Modi government has attempted to use import duties on parts such as circuit boards to encourage companies to assemble more of the phone locally, but the lion’s share of the components are still flown in from China, South Korea, Taiwan or elsewhere.

Complicating a complete supply chain shift into India are the political sensitivities in China about seeing this work go to factories there. Chinese engineers and technicians who install or service machinery for manufacturers like Foxconn have in some cases faced visa delays. Relations between China and India remain tense, meaning the company will have to navigate potential attempts by China to slow the process of moving component suppliers and specialist equipment.

Brazil — midway between India and China on cost, says Shah — could be an even more favourable option for Apple if the US were to go through with its threat to put additional 26 per cent tariffs on India. With a domestic market bigger than Vietnam’s, Apple can easily ship from Brazil to the rest of Latin America, Canada and western Europe, alongside the US.

An uncertain future

Exactly how tariffs will affect the iPhone alongside other Chinese-made smartphones and electronics is unclear. After excluding phones, chipmaking equipment and certain computers from his so-called reciprocal tariffs, President Trump launched a national security review to assess how tariffs should be applied on semiconductors and electronics. Nobody, he says, is getting “off the hook.”

The impact of the tit-for-tat on consumers is also uncertain. TechInsights predicts the cost of an iPhone 17 will increase by 10-30 per cent in the second half of 2025. However, Morgan Stanley suggests Apple will be able to stave off price rises in the medium term using a combination of measures, including a greater mix of India assembly, sharing the burden of rising costs with suppliers and discontinuing underperforming lower-storage models.

Other potential disruptions loom. In response to reports that the Trump administration planned to use trade talks with multiple countries to isolate China, Beijing warned it will retaliate against any nation negotiating deals at the expense of its interests. Any broader constraints on Chinese exports crossing borders would ripple through Apple’s supply chain.

“This is a pivotal moment for Apple because of their dependence on China, and the dual nature of that dependence — as both a supplier and a growing consumer market,” says Tsay. “And is China going to let Apple go that easily? Because China needs Apple too.”