What the US stands to lose from a dented dollar

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

The Trump administration has already dented the dollar’s status as a key load-bearing pillar of global finance. It would miss it greatly if it went.

It still feels wild to be discussing all this. For years, banging the drum for the dollar surrendering its role as the dominant reserve currency was a niche hobby for crackpots. Some big investors still insist the mighty dollar is here to stay, with no serious alternative to its status. Others point out that dollar doubters are conflating the recent spell of weakness in the buck with its role as a safe harbour and lubricant for global trade.

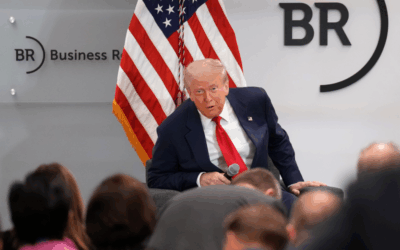

Both of these pushbacks, though, are blind to the scale of disruption in security policy and geopolitics since Donald Trump re-entered the White House. It is sensible, then, to think about what the US stands to lose. The guess right now is that, in markets and in big power politics, it will be more short-termist, less resilient in any passing crisis, and much more reliant on the kindness of strangers.

Adam Posen, the long-standing president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, is among the heavy-hitting economists who have been through a conversion on this matter. Back in 2008, he wrote a paper titled “Why the Euro will Not Rival the Dollar”, noting then that “the euro is at a temporary peak of influence, and the dollar will continue to benefit from the geopolitical sources of its global role which the euro cannot yet or soon, if ever, match”.

At that point in time, Trump was busy with the opening of his last major construction project, the gleaming Trump International Hotel and Tower in Chicago. Posen, like the rest of us, can be forgiven for failing to imagine back then that Trump might end up as the leader of the free world, again, in 2025. But here we are.

Now, Posen said in a fascinating online presentation last week, the president’s abrupt shift in foreign policy is posing a direct and serious risk to the dollar’s foundations. The greenback’s decline since Trump’s April 2 announcement of so-called reciprocal tariffs is one thing, an instinctively understandable reflection of likely weaker US growth ahead. But the fact the dollar has dropped at the same time as the value of long-term US government bonds is a different thing altogether — not slam-dunk proof that the dollar’s dominant reserve currency status is dead, but very solid evidence that it is injured.

One crucial element here is that not all US government bonds are created equal. When Trump blasted markets with his announcement of outsized trade tariffs, short-term Treasuries with maturities of around two years jumped in price — a typical reflection of expectations for a shock that might necessitate interest rate cuts. The so-called long end of the market, however, took a different path, a highly unusual quirk that is “consistent with a reduction in [their] safe-asset hedging property”, in the words of a new analysis from Viral Acharya and Toomas Laarits at New York University Stern School of Business.

In normal times, bonds and currencies bob higher and lower based on growth, inflation and interest rates. But these are not normal times, and as we are seeing, the less visible foundations of foreign policy and geopolitics form the ground on which that all sits. That makes it hard — not impossible but hard — to see how the dollar and Treasuries can reclaim their historic role as reliable safety valves for skittish markets.

Unless this imbalance between short- and long-term Treasuries resets, this means the US is likely to lean much more heavily on cheaper short-term debt issuance. Typically, the US is such a staid, safe and reliable borrower that the Treasury can afford in effect never to pay its debt back — it can just issue new bonds to pay off the old ones, over and over again. Tilting more to the short than the long term means this will be a much more frequent task, requiring the US to keep its creditors sweet to try and damp down borrowing costs.

The enormous privilege of hosting the currency and the bond market that the world wants to own in a crisis has also meant that the US can borrow its way out of trouble, even homegrown trouble, much more easily than any other country. Historically, it has managed to keep crises short by tapping into a reliable well of investment at a reasonable cost, and stimulating its way out of almost any fix much more freely than other nations, which often see their borrowing costs rise when the going gets tough.

The new US administration may have believed this is just how the world works. That’s understandable, but not to be taken for granted, and Europe would love a slice of that magic.

Safe assets are safe because everyone thinks they’re safe. The US is well on its way to finding out the long-term cost when that cracks.