The Novels We’re Reading in May

Books

The Novels We’re Reading in May

From the Gulf as a modern Wild West to sisterhood in Singapore.

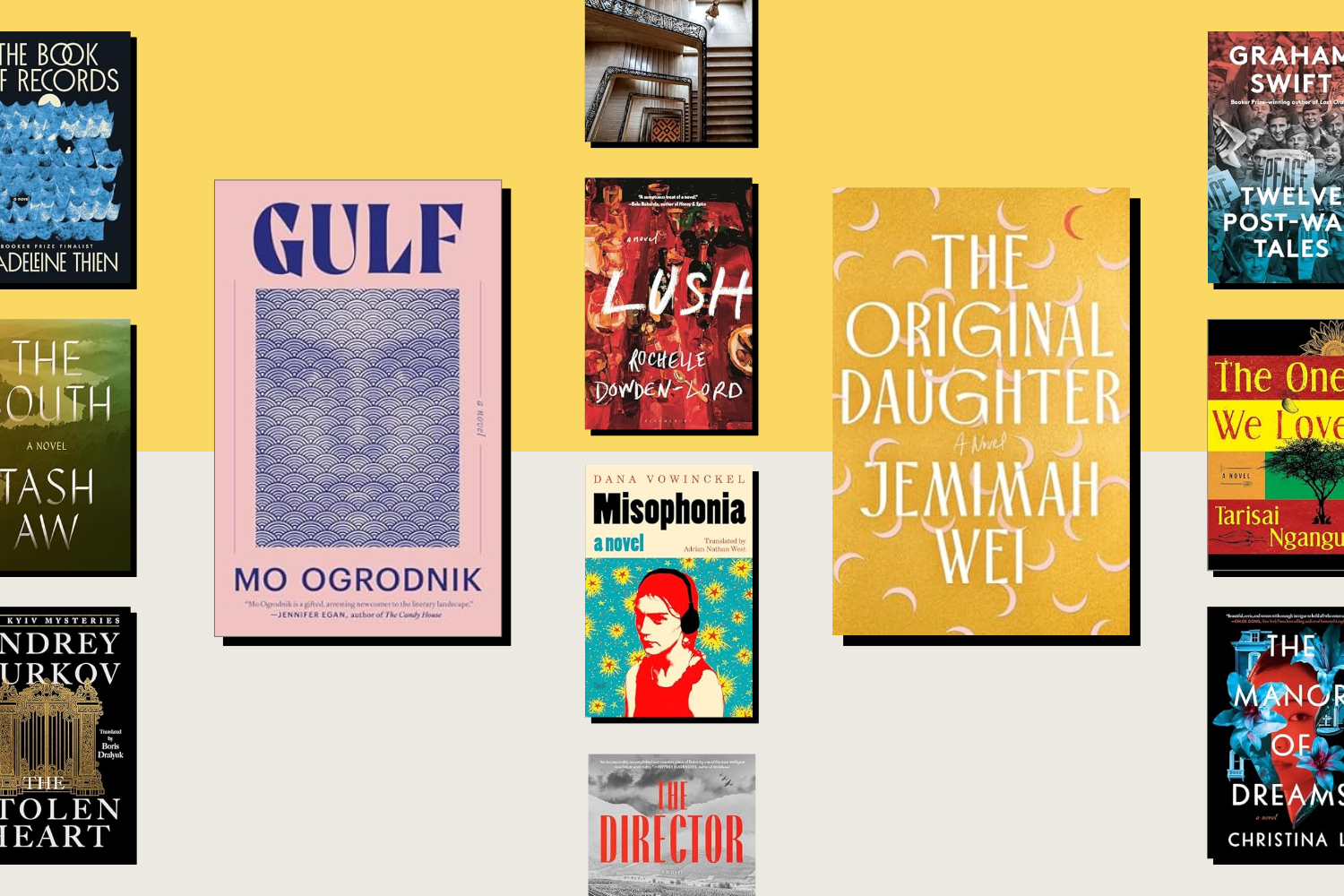

Publisher book covers

This month, we’re immersing ourselves in novels that explore the personal and societal costs of ambition in two of the globe’s economic powerhouses: the Gulf and Singapore.

Gulf: A Novel

Mo Ogrodnik (Summit Books, 432 pp., $29.99, May 2025)

This month, we’re immersing ourselves in novels that explore the personal and societal costs of ambition in two of the globe’s economic powerhouses: the Gulf and Singapore.

Gulf: A Novel

Mo Ogrodnik (Summit Books, 432 pp., $29.99, May 2025)

Later this month, U.S. President Donald Trump will take his second trip abroad since returning to the White House, traveling to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The visit is a reflection of those countries’ growing geopolitical clout. So too is American filmmaker Mo Ogrodnik’s debut novel, Gulf, an uncomfortable portrait of a region whose economic allure is undergirded by troublesome social and political realities.

The book follows five women from around the world who land in the Gulf for a variety of personal and professional reasons. Justine is a curator from New York City whom the Emirati government has scouted to develop an exhibit on the falcon—the “lion of the skies” and the emblem of the UAE—at the Zayed National Museum in Abu Dhabi. Dounia is a wealthy Saudi mother based in the port city of Ras al-Khair. She struggles in the postpartum period; “like an abandoned buoy, she float[s] out to sea, losing contact with the world” while subjecting her household to a range of emotional outbursts. Dounia’s life becomes intertwined with that of Flora, the Filipina domestic worker she hires—and abuses—under the notorious kafala system.

Meanwhile, in Raqqa, Syria, a young Zeinah is forced to marry an Islamic State fighter “to secure her parents’ safety.” She at once detests the group but also finds that “ISIS gave her a sense of community and purpose.” Farther south, Eskedare, a girl from Ethiopia, seeks to follow her great love to Qatar—to build stadiums for the 2022 World Cup—but ends up being trafficked first to Yemen and then to the UAE, where she encounters Justine.

Ogrodnik, a professor at New York University who previously worked in Jordan and the UAE, is unsparing in her descriptions of the Gulf’s glitzy deceptions. It is a place where the “landscape felt impenetrable” and contrived air-conditioned environments reign supreme. The “Dream Development” gated community where Dounia lives “would one day overlook a golf course” but, for now, is “a dumping ground for cement pilings.” Flora feels that “everything took so much effort” in Saudi Arabia.

In Abu Dhabi, “People referred to the Gulf as the new world, the Wild West,” Justine observes. “Every foreigner she met was here for money or to stake a claim in something.” Her husband cautions her that “it doesn’t end well” for most who move to the Gulf for financial reasons. Among them are girls like Eskedare, who are known in Ethiopia as “Gulf-return girls: eyes-to-the-ground girls, girls gone missing, girls gone dead.” Justine’s teenage daughter, who attends an international school, complains that, in Emirati curricula, “It’s just, like, poof, the Holocaust never happened. Poof, no queer people.”

Gulf would be too straightforward if it were solely a critique of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. But Ogrodnik offers an equally keen rebuke of Western behavior in the region—and exposes inconsistencies in U.S. foreign policy.

For instance, while terrorizing Flora, Dounia muses about international condemnation of the kafala system—“Outrage from Western institutions whose power was predicated on genocide and slavery but who now signaled virtue by policing the world for labor infractions and human rights violations.”

And for Justine, “Since coming to Abu Dhabi, she’d been confronted with an engagement and connection to the world she’d not experienced at home. The acts of the United States abroad had become personal, knowable, and felt.”

Despite its numerous haunting storylines, Gulf is a beautiful read. Ogrodnik’s prose is intricate and artistic, lending color to even the most mundane parts of the plot. When Justine clears up space on her hard drive, Ogrodnik writes poetically of the most rigid thing there is—algorithms: “She emptied the trash and listened to the electronic sound of paper crumpling, ones and zeroes colliding.”—Allison Meakem

The Original Daughter: A Novel

Jemimah Wei (Doubleday, 368 pp., $30, May 2025)

Jemimah Wei’s The Original Daughter is a claustrophobic novel, which is fitting for a tale propelled by the suffocating intensity of sisterhood. Though it spans decades, the book largely takes place in the confines of a one-bedroom apartment in Singapore’s Bedok district, where the narrator, Genevieve, lives with her parents and grandmother—until one day, Arin, a descendent of a relative long presumed dead, is “dropped into [her life], fully formed, at the age of seven.”

When Genevieve moves to Christchurch, New Zealand, more than halfway through the novel, it’s a welcome reprieve—and a masterful move from Wei, a former television presenter from Singapore. Wei cleaves her narrator from all she’s known in part to reveal a simple truth: Although Genevieve is relieved to shed her old life, she recognizes that her halcyon Christchurch days can’t last, and that “it’s the frictions of living that weave you to a place.”

It is those frictions that are the heart of Wei’s debut. The Original Daughter is full of lush, descriptive prose, reserved not just for emotional excavation but also the minute details of place. Genevieve and Arin live in a community where “[e]veryone was in everyone’s business, the neighborhood running smoothly on the currency of gossip, and that wasn’t a bad thing, it demonstrated interest, care, to ask after the sundry shop uncle’s university-faring son, or the drink stall auntie’s perpetually frozen shoulder.”

That immense care for the affairs of others also proves oppressive, as does Singapore’s cutthroat culture of work and study (which the city-state’s own prime minister has critiqued). At times, Wei references the rat race with offhand humor: “When I saw, carved roughly with a penknife into the side of my desk, welcome to hell, I felt thrilled this was a hell that admitted only a select few,” Genevieve notes her first day of junior college. As the novel unfolds, though, both Genevieve and Arin are increasingly wounded by “the endlessly repeating pattern of struggle [that] seemed to unroll into our future.”

As Arin’s career as an actress takes off, the girls’ relentless push for success deepens the rift between them. But even in their ugliest moments—in their stubbornness, in their willingness to let bitterness fester, in their displays of cruelty and unvarnished hurt—warmth radiates from Wei’s characters and their utterly human shortcomings.

The Original Daughter is an assured debut, the kind of novel you want to luxuriate in, even when its Ferrante-esque attention to the consuming nature of de facto sisterhood is anguishing. In its excavation of Genevieve and Arin’s relationship, the book forces us to confront, again and again, perennial coming-of-age questions: What do we owe to those who raise us, and how much are we bound by the places we’re from?—Chloe Hadavas

May Releases, in Brief

A 17th-century Jewish scholar, a philosopher fleeing Nazi-era Germany, and a Tang Dynasty poet converge in Canadian author Madeleine Thien’s The Book of Records. Tash Aw’s The South offers a portrait of a fracturing family at an old orchard in 1990s Malaysia. In Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov’s The Stolen Heart, translated by Boris Dralyuk, a young detective investigates illegal profiteering after World War I. The late Argentine writer Aurora Venturini’s 1992 novel, We, the Casertas, is translated into English by Kit Maude. In The Director, translated by Ross Benjamin, German literary giant Daniel Kehlmann fictionalizes the life of filmmaker G.W. Pabst, who worked under the auspices of the Third Reich.

Four oenophiles confront personal crises over a bottle of one of the world’s rarest wines in British author Rochelle Dowden-Lord’s debut novel, Lush. Dana Vowinckel’s Misophonia, translated by Adrian Nathan West, explores family obligations and cultural disconnect across Berlin, Chicago, and Jerusalem. In Twelve Post-War Tales, Booker Prize-winning Graham Swift examines life after tumultuous historical moments, from World War II to 9/11. Zimbabwean journalist Tarisai Ngangura makes her literary debut with The Ones We Loved. And a late Chinese actress’s decaying California mansion forms the backdrop for Christina Li’s gothic thriller, The Manor of Dreams.—CH

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Allison Meakem is an associate editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @ameakem.bsky.social X: @allisonmeakem

Chloe Hadavas is a senior editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @hadavas.bsky.social X: @Hadavas

More from Foreign Policy

-

A drawn illustration of a Trump whirlwind on a red background Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

-

Marco Rubio is seen up close, sitting on a couch beside J.D. Vance. Marco Rubio’s Soulless Crusade

The U.S. secretary of state stands for no principle other than serving the man who appointed him.

-

Soldiers from various NATO allies take part in a military exercise at the Smardan Training Area in Smardan, Romania, on Feb. 19. America Will Miss Europe’s Dependence When It’s Gone

European self-reliance for security will cost U.S. jobs, profits, and influence.

-

A collage photo illustration shows Donald Trump gesturing with arms wide. In front of him are headshots of Benjamin Netanyahu and Vlodymyr Zelensky, images of immigratns and ICE police, a tattered EU flag and America First signs. Trump’s First 100 Days on the Global Stage

Ten thinkers on what to make of the opening salvo of the president’s second term.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.