Trump’s tariffs will boomerang on US exporters

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Greetings! Two weeks ago I pointed out some problems in the view that trade deficits hurt the manufacturing sector, that domestic manufacturing production has a straightforward link to manufacturing jobs, and that, therefore, it makes good sense to want to rein in trade deficits and seek “balanced trade”. As I pointed out, a surprising number of people agree with US President Donald Trump about this, even some who disagree violently with him on everything else.

What I didn’t dwell on is how you might go about reducing trade deficits in the first place (if you thought that would be a good idea) and, specifically, whether higher US tariffs will actually achieve more balanced trade. So this week, I want to spend some time on why that is unlikely. Share your thoughts and reactions at freelunch@ft.com.

Economics is sometimes rightly derided for developing fancy models and statistics to prove what everyone already knew. But economics at its best has ways of showing that the economy can behave in ways that are totally unexpected and paradoxical — new knowledge without which we are likely to pursue policies that achieve the opposite of what we want. No field of economics is richer in these revelations than the theory of international trade.

The Lerner Symmetry Theorem is a famous finding in trade theory. In 1936, Abba Lerner showed that an import tariff and a tax on exports have the same economic effect: they shrink both exports and imports. This is baffling; we would naturally think that punishing imports should shrink the trade deficit (or increase net exports), while taxing exports should increase it (or shrink net exports).

But following our natural beliefs in policymaking would lead us astray whenever the Lerner equivalence holds. If tariffs punish exports as much as imports, it is obviously futile to use them to address a supposedly problematic trade deficit. And it’s especially futile if your goal is to make your economy a larger manufacturing exporter.

I return to the policy implications below, but let’s first take a moment to get an intuitive understanding for why Lerner symmetry may hold.

The initial effect of import tariffs is, of course, to make imports more expensive, and therefore encourage buyers to look for alternatives. (That is indeed the point, if Trump’s words are anything to go by. The question is how this diverted demand, which now will be for domestically produced goods, is going to be met.) Provided there are not a lot of unused resources — and the US has been firing on all cylinders — labour and capital will have to be drawn away from other production. And some of those resources that will be redeployed will be those already involved in manufacturing for export — and that is one reason why exports will fall.

(For a depressed economy operating well below its potential, things are different: tariffs could possibly boost aggregate demand — reducing it in other countries — and restore full employment. But this would only be a short-run effect, and not the best policy to achieve even that.)

Another reason why tariffs hurt exports is that when supply chains cross borders, tariffs drive up the cost of imported inputs, hurting the productivity of manufacturing, which, in turn, will make the sector less able to export. Many US exports, notably cars, contain up to 20 per cent imported content, Torsten Sløk of Apollo highlighted last week.

A third reason could be that if the fall in import demand strengthens the currency, the appreciation hurts exporters — though the US dollar has gone the other way since Trump’s tariffs announcement on “liberation day”.

(The original Lerner theorem looked at simple, balanced economies. You can read here a recent formal explanation by Arnaud Costinot and Iván Werning which shows that the old result generalises well to more realistic situations with imbalanced trade, limited competition, behavioural biases, cross-border investments and imperfect price adjustments. Here is a similar exercise from Jesper Lindé and Andrea Pescatori at the IMF pointing out when the theorem generalises and conditions under which it no longer holds. Both are from 2017; it’s perhaps no surprise that several research papers seeking to update the Lerner theorem appeared shortly after Trump first took office.)

With the theory in mind, we can make sense of the striking results of the Kiel Institute’s estimates of the effects of “liberation day” — an illustration of Lerner symmetry in action. Julian Hinz, Isabelle Méjean and Moritz Schularick calculate that Trump’s trade policy (as of April 9, compared with end-2024) will shrink trade between the US and China by almost half, and perhaps more than 70 per cent in the long run. But look more closely at what happens to exports:

Exports from the US are projected to slide by 17 per cent, or about $500bn on current numbers. That is more than the fall in its imports from China and, importantly, a much steeper fall than for China’s own exports or global exports as a whole (both at about 5 per cent). The authors do not report how much US total imports would fall, but I asked Schularick to check the numbers, and their model estimates a total drop of 5 per cent in imports, which comes to about $200bn. Much less, in other words, than the export loss. If these sorts of estimates are anywhere near borne out, Trump will permanently expand the trade deficit, and not shrink it at all.

The difference between China and the US is that only the latter is raising tariffs on everyone (China is only retaliating against the US). That prevents importers and producers from finding alternatives to China, whereas China can both replace US-origin imports and find new markets for its exports. As Martin Wolf pointed out last week, “it is easier to replace lost demand than missing supply”, especially if you don’t impose a tax on the attempt.

The lesson here is that taxing any trade is tantamount to taxing trade generally — in both directions. Does this mean trade policy cannot affect the trade balance at all? No. If you take tariffs to the limit, they shut down all trade, and so you achieve a trade balance by definition (zero imports and zero exports).

So it is obviously possible to eliminate a deficit through tariffs, but you may have to practically cut yourself off from the world economy to do so. The trillion-dollar question is whether Trump has the stomach to go that far, and if he does — how will an autarkic US fare, and how well can the rest of the global economy do with a US-sized hole in it? Send me your views.

Other readables

-

Cultural coda: As part of its VE Day coverage, BBC Radio 4 last weekend had a fascinating interview with Lord Norman Foster on post-1945 architecture and the new political principles it embodied. Foster famously designed the new buildings for reunified Germany’s parliament, juxtaposing the heavy classical Reichstag building with glass galleries, allowing the public to literally look down on parliamentarians in the new Bundestag hemicircle. It brought back all I learnt when writing this essay about the violent political changes reflected in Warsaw’s many-layered architecture.

-

In my latest column, I explain how Trump has offered Europe a golden opportunity to make the euro dethrone the dollar from its global role. Hélène Rey tackles the same topic.

-

Cory Doctorow suggests the perfect retaliation to Washington’s trade war: repeal “anti-circumvention laws” that US multinationals have lobbied so successfully for in other countries.

-

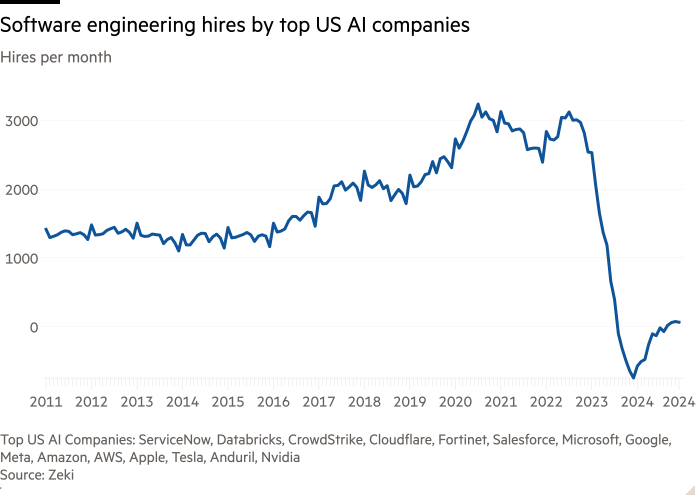

If not tariffs, could robots come to the rescue of US manufacturing?