The case for universities

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I’ve just returned from a tour of British universities with our 16-year-old twins. The boys can’t wait to finish school and start their degrees, and I’m psyched for them. I grew up around universities. My dad has been an academic for over 60 years. My sister is one too. I’m with Nils Gilman, former associate chancellor of Berkeley, who writes: “No other institution ever invented has been anywhere near as good at educating a broad population to a high level of technical competency, nor at creating the conditions for the discovery of new facts about and conceptions of the world, nor at maintaining the knowledge already created.” The UK has the advantage over the US in possessing a government that mostly recognises this.

Yet universities are in crisis internationally, far beyond Donald Trump. Perhaps no other existing institution is less in sympathy with our times. In fact, that’s largely why Trump is attacking them.

Universities are built on the implicit claim that there’s a hierarchy of knowledge. At the top are people who spend lifetimes gathering expertise, achieving accreditations such as PhDs and professorships, and testing their findings in writings reviewed by their peers. What accredited academics think about climate change or racism simply has more validity than random people’s views. That privilege of knowledge always offends, but particularly in an era when every ignoramus can broadcast on social media. When the US health secretary, Robert F Kennedy Jr, urges parents to “do your own research” on vaccines, he is denying the basic principle of academia. Rightwing populists consistently take this position. I wonder why academics are “biased” against them.

Scholarly enquiry requires what Columbia University’s former president Lee Bollinger calls “an abnormal openness to ideas”. But polarised people don’t want openness. They want academics to endorse their opinions. I witnessed this dynamic last month at an event at the Paris university Sciences Po. Several heads of universities in Europe and North America had gathered to express a shared message: their institutions wouldn’t take stances on political issues, such as the war in Gaza. Individual academics and students could form their own views.

But each time a head of a university tried to speak, a masked student would rise from a group of pro-Palestinian protesters in the audience and read a statement of several minutes accusing that official’s university of being “complicit with Israeli genocide”. The protesters didn’t want a discussion. They drowned out any attempts at one by making discordant noises on sound systems they had brought in. I don’t think they did anything to help people in Gaza, whose problem isn’t western universities but the Israeli army.

Cornelia Woll, president of Berlin’s Hertie School, asked the hall, “Why do so many people hate universities?” Her answer was that both the protesters and certain governments wanted to control “the substance” of what universities said. In fact, Woll said, what was distinct about academia was not its substance, but “the process and the method” it followed to arrive at “shared facts and knowledge”. Unfortunately, she shrugged, those aims were “much too esoteric” for most critics.

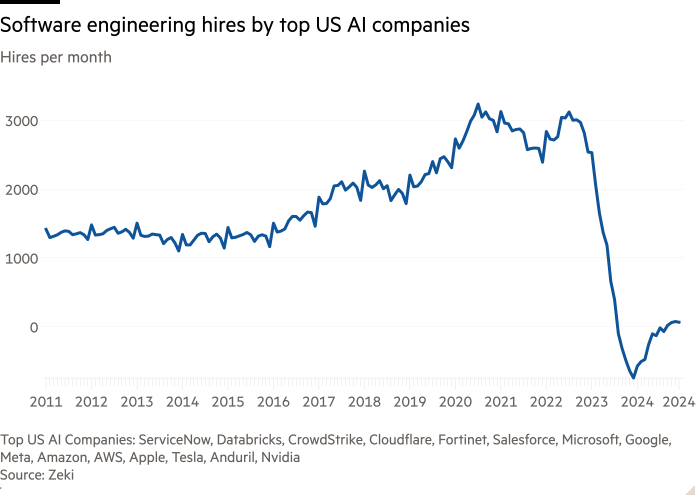

During the protesters’ speeches, many of us in the hall scrolled on our smartphones — the devices that have decimated concentration and reading skills. Now AI has begun inflicting even greater damage on universities. It already writes many student essays. The first workers replaced by AI may be mediocre undergraduates.

The undervaluing of universities takes different forms in different countries. In the UK, it expresses itself through the state’s underfunding of higher education and hostility to the immigration that sustains these institutions. The University of Manchester’s turnover exceeds British Steel’s, but which enterprise gets more help from the government?

I see the effects on my daughter, now in her first year at a British university. She’s having a wonderful academic experience, at least when the university operates. She has just started a five-month period without any teaching, presumably because of budget cuts. I used to think that the UK’s much-vaunted undergraduate degree, supposedly three years long, was really just 18 months given the long holidays. It’s now less than that.

Universities such as Bologna (founded 1088), the Sorbonne (1253) and Harvard (1636) are among the oldest functioning institutions in their countries. They’ll survive. But they may be shrinking into signifiers of class, diploma factories, fun parks and networking clubs.

Email Simon at simon.kuper@ft.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram