The Ukrainian Troops Who Will Never Stop Fighting

The Ukrainian Troops Who Will Never Stop Fighting

Behind enemy lines, Ukrainian agents are committed to tormenting their Russian occupiers—even if there’s a ceasefire.

A former Russian special forces sergeant who now fights for Ukraine after living in the country for a decade with his Ukrainian wife, gestures to keep quiet as he moves along frontline tenches towards a Russian position around 150 metres away, on October 27, 2022 in Zaporizhzhia oblast, Ukraine. Carl Court/Getty Images

KYIV, Ukraine—On April 26, Ukrainian partisans operating in the Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine knocked out a railway transformer near Stanytsia Luhanska, a Russian-captured town in easternmost Ukraine that intersects a critical Russian supply line. On April 16, more railway hardware was set afire in occupied Melitopol in the Zaporizhzhia region, a key transport hub for Russian troops and transit point for ammunition, fuel, and other military kit heading to the front near Robotyne and Kamianske. And, on April 13, a pro-Ukraine partisan cell sabotaged a Russian tank in Donetsk oblast by setting it on fire.

On its Telegram channel, the pro-Ukrainian underground movement called Atesh (“fire” in Ukrainian and Russian) claimed responsibility for all three attacks. It’s further proof that Ukrainian operatives are more engaged and efficacious than ever in the “temporarily occupied territories,” as Ukraine refers to Crimea, Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia. Their goal: to snarl the workings of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war machine by wrecking its infrastructure, murdering its officers, and tying down occupation personnel.

KYIV, Ukraine—On April 26, Ukrainian partisans operating in the Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine knocked out a railway transformer near Stanytsia Luhanska, a Russian-captured town in easternmost Ukraine that intersects a critical Russian supply line. On April 16, more railway hardware was set afire in occupied Melitopol in the Zaporizhzhia region, a key transport hub for Russian troops and transit point for ammunition, fuel, and other military kit heading to the front near Robotyne and Kamianske. And, on April 13, a pro-Ukraine partisan cell sabotaged a Russian tank in Donetsk oblast by setting it on fire.

On its Telegram channel, the pro-Ukrainian underground movement called Atesh (“fire” in Ukrainian and Russian) claimed responsibility for all three attacks. It’s further proof that Ukrainian operatives are more engaged and efficacious than ever in the “temporarily occupied territories,” as Ukraine refers to Crimea, Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia. Their goal: to snarl the workings of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war machine by wrecking its infrastructure, murdering its officers, and tying down occupation personnel.

“About every other day there’s an act of sabotage carried out by pro-Ukraine forces,” Yuriy Matsiyevsky, a professor at Ukraine’s Ostroh Academy National University who studies Ukraine’s resistance movement, told Foreign Policy. He cited assassinations, ambushes, arson, poisonings, kidnappings, and bombings of communication and energy infrastructure. “Even though Russian control has become ever tighter, the Ukrainian underground applies consistent pressure. They make it harder for Russia to communicate, to move and transport people and supplies to the front,” he said.

In the event of a cease-fire that cedes these territories to Russia, Matsiyevsky believes that these forces would fight on. “The territories occupied by Russia are already under its de facto control,” he wrote to Foreign Policy in an email. “Russia is pursuing a genocidal policy against Ukrainians in those areas. The recognition of its de facto control does not change the reality on the ground for Ukrainians, which is why resistance will continue—either until Ukraine regains these territories, or, as was the case with the occupation of western Ukraine in 1939, until the resistance is forcibly suppressed.”

“It’s guerrilla warfare, which Ukrainians know from World War II,” said Vladimir Zhemchugov, a Kyiv-based agent of the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ special operations branch, who had been active in the Luhansk partisan movement after the 2014 invasion of the Donbas. He said there are about a dozen groups, including Atesh, that are regularly disrupting Russian operations behind enemy lines—and, ever more so, reaching deep into the hinterland of Russia proper.

Ukraine’s covert resistance in the occupied regions constitutes yet another theater of warfare beyond the dug-in southern and eastern fronts, in addition to, for example, the Black Sea theater, the technology race, and the public relations rivalry in the world beyond Ukraine and Russia. Like so much of Ukraine’s defense, it is self-organized, young, tech-savvy, and includes many women. Ukraine’s covert operations sporadically upend Russian logistics and cause delays in Moscow’s deliveries of equipment and spare parts, as well as divert Russian occupation personnel from duties elsewhere. They carry out hits and—just as critically—pass along intelligence that Ukrainian drone units use to target Russian military assets, including radars, anti-aircraft systems, helicopters, and ships.

Since so much about the covert partisans is necessarily restricted—for obvious reasons of operatives’ safety—Ukraine’s security services rely on informal sources, like Zhemchugov, to tell their story to Ukrainians. Zhemchugov isn’t just anybody in the world of the Ukrainian underground; he’s known as “Ukraine’s first partisan.” An ethnic Russian born in Luhansk, he experienced the Russian military’s terror firsthand when it took his city in the summer of 2014. The Ukrainian army retreated, but smatterings of then-unorganized resisters remained behind. Zhemchugov, 43 years old at the time, sold his plastics company in Georgia to buy weaponry from Russians on the black market and proceeded, with a handful of like-minded fighters, to harass the Russian forces: with sniper fire, mines, and the sabotage of supplies.

Only in late 2014 did Ukrainian authorities accept the autonomous saboteurs as their own and begin handling them as agents. Zhemchugov’s cell completed 25 operations before he stumbled on a land mine in 2015, which blew off both of his arms and blinded him. In Russian captivity for months, Zhemchugov experienced the grim fate of captured partisans: beatings, starvation, torture. Eventually released as part of a prisoner exchange, he underwent surgery after surgery in German hospitals, where he ultimately regained his eyesight. Today, he wears prosthetic arms. Upon his return to Ukraine, he assisted Ukrainian special operations to grow its portfolio of agents and foment civilian resistance to the occupation.

Today, Zhemchugov said, the armed partisan movement includes roughly 3,000 operatives, while the civilian resisters waging disobedience number about 10,000 (the latter write anti-Russian graffiti, post Ukrainian flags in public places, burn Russian propaganda, and, in any way they can, slow the processes of Russification). Three branches of the Ukrainian state run agents: Ukraine’s main internal security agency, the military intelligence service, and Rukh Oporu of the Special Operations Forces Command. Some of the movements have names—such as, in addition to Atesh, the Donetsk Partisans, Luhansk Partisans, Crimea Combat Seagulls, Mariupol Resistance, Yellow Ribbon Movement, SROK, and Zla Mavka—while others are entirely covert and unnamed.

Atesh is the largest single force behind the front. Born in September 2022 in Crimea, it began operations with the following proclamation on Telegram: “We are Atesh, an underground movement made up of Crimean Tatars, Ukrainians, and Russians. We have infiltrated the Russian army and are working to destroy it from within. We will expose coordinates and data on supply depots, soldiers, and equipment. We will sabotage warehouses and command centers.” Atesh’s Telegram channel now has around 45,000 subscribers.

Another unit is the all-female Zla Mavka movement that emerged in the occupied city of Melitopol in early 2023, and is named after a female spirit from Ukrainian folk mythology. The members—called mavkas—operate anonymously and independently of one another. They paste up posters and leaflets, counter Russian propaganda, and do whatever else they can to keep the occupiers on edge, ensuring that they never feel completely secure. But that’s not all. The women lace Russian food with poisons: One such event killed 12 Russian troops. Yet another group, the Crimean Combat Seagulls, poisoned and killed 24 Russian soldiers by lacing arsenic and strychnine into their vodka.

The on-the-ground operatives say that Russian security is omnipresent and that their movements are highly proscribed. But this doesn’t stop the intelligence gathering that happens constantly, they say. Ukraine’s digital ministry created the chatbot eVorog (“eEnemy”) in Telegram to report the movements of Russian military and equipment to the Ukrainian security services. “If you see Russian equipment or occupiers,” it tells its users, “send the exact geolocation of their location, as well as photos and videos.” A unit within the ministry then verifies the sender’s identity through the Diia app, which gives Ukrainian citizens access to their digital documents, such as ID card, foreign biometric passport, student card, and driver’s license.

This technology has paid off handsomely: Just recently, on May 2, the Ukrainian Armed Forces launched its largest drone attack of 2025 on occupied Crimea, hitting four Russian airfields on the peninsula at Saky, Kacha, Hvardiiske, and Dzhankoi. According to Ukrainian sources, the hits took out at least four radars used for missile guidance and two S-300V long-range surface-to-air missile systems, which “disrupted Russian air defense capabilities in Crimea.” On May 5, Sevastopol’s Russian “governor” called off the May 9 Victory Day parade to commemorate the Soviet victory in World War II due to safety risks.

In February, Atesh announced on Telegram that the Russian army command was withdrawing select air defense missile units from Crimea due to the targeted Ukrainian drone attacks. In the same message, Atesh claimed that it still has agents within the Russian Armed Forces.

“Russia’s counterintelligence system in the temporarily occupied territories is very well developed,” Kyrylo, a special forces operative who asked to remain anonymous, told Foreign Policy. Under these conditions, “it’s extremely difficult to control an entire network of agents,” he said, and often they fall into enemy hands. Even possession of a telephone with the encrypted Signal messaging app is grounds for arrest. Because the Ukraine-Russia borderlands are so militarized, he said, Ukraine ferries the partisans supplies through the Baltics and then Russia proper.

Since they are not officially soldiers, underground agents captured by Russians are not treated according to Geneva Conventions stipulations. (This said, bona fide Ukrainian troops are also regularly tortured and otherwise mistreated.) The Russian courts hand down draconian sentences, even for children who resist the regime. In April in Donetsk, for example, a 17-year-old was sentenced to six years for “treason,” namely supplying the Ukrainian internal security agency with information on Russian troop locations.

For some time now, the security services have been expanding their reach beyond Ukraine—into Russian territory, even as far as Moscow, as the April 25 assassination of a Russian general proved again. “We’re exporting the war to inside Russia,” said Kyrylo, the special operations agent, who noted that Atesh is one organization that operates inside Russia.

“The Ukrainian underground movement is at least several times more effective than Russian sabotage actions on our territory,” he said. “That’s because [the occupied territories] are their home, it’s rightfully theirs, and they’re being suppressed.” Despite losses on the hot fronts, Ukraine is prevailing in other theaters of the war, including covert operations behind the front lines.

The determination of these partisan movements has lent Ukraine’s negotiators additional leverage in any cease-fire talks with Russia. But they could also complicate such negotiations, too. Even in the event of a cease-fire, there’s good reason to think they would soldier on, even if their commanders order that they lay down their arms. The de facto loss of any of these territories, or even parts of them, would be a very bitter pill for those who have risked their lives to liberate their homelands.

Paul Hockenos is a Berlin-based journalist. His recent book is Berlin Calling: A Story of Anarchy, Music, the Wall and the Birth of the New Berlin (The New Press).

More from Foreign Policy

-

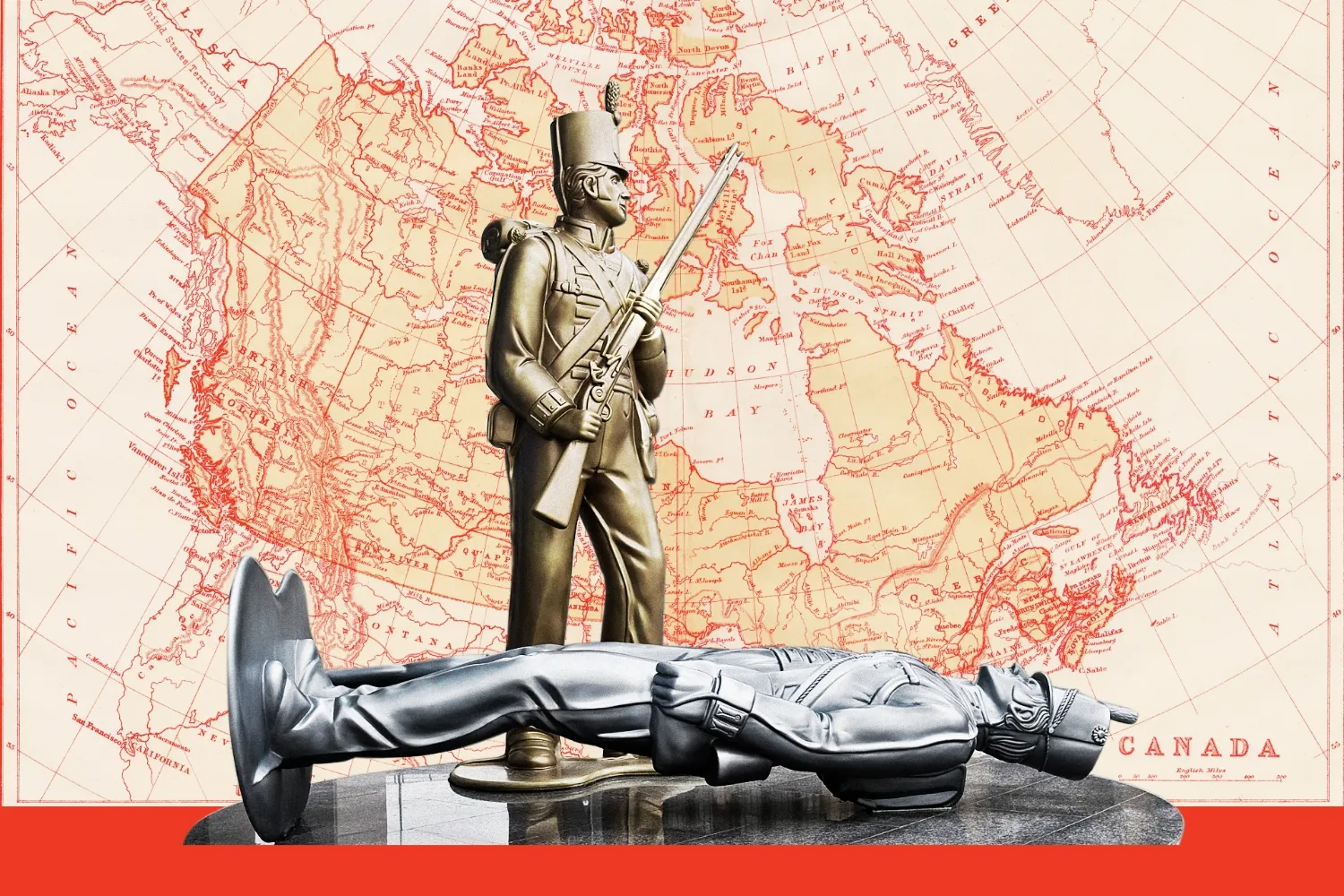

Eight people dressed in camouflage military combat uniforms wade across a river, the water up to their waists. The soldiers carry large backpacks along with their rifles. Snowcapped mountains and a thick forest of evergreen trees loom in the distance. Get Ready for the Aleutian Island Crisis

As conflict heats up in the Arctic, foreign adversaries eye Alaskan territory.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks to reporters before boarding Air Force One at Morristown Municipal Airport in Morristown, New Jersey, on April 27. Trump’s First 100 Days Reveal a ‘Strongman’s’ Unprecedented Weakness

No U.S. president has ever surrendered global power so quickly.

-

An elderly man and woman sit on the ground, the man on his knees as he sorts through something on the ground. Behind him are a rusted cart and bicycle in front of a paint-smeared concrete wall and a battered corrugated metal sign with the words USAID: From the American people” on it. What Trump’s New Budget Says About U.S. Foreign Policy

The president wants to significantly pull back on many of America’s traditional global engagements while spending more on the border and defense.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump listens to Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a cabinet meeting in the White House in Washington, D.C. Rubio’s Reorganization Plan Is a Wrecking Ball

The State Department revamp goes far beyond streamlining—it will devalue human rights and strip away critical expertise.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.