Both Xi and Trump Want the Other to Call Them First

Analysis

Both Xi and Trump Want the Other to Call Them First

A conflict over face is tangling up the trade war’s resolution.

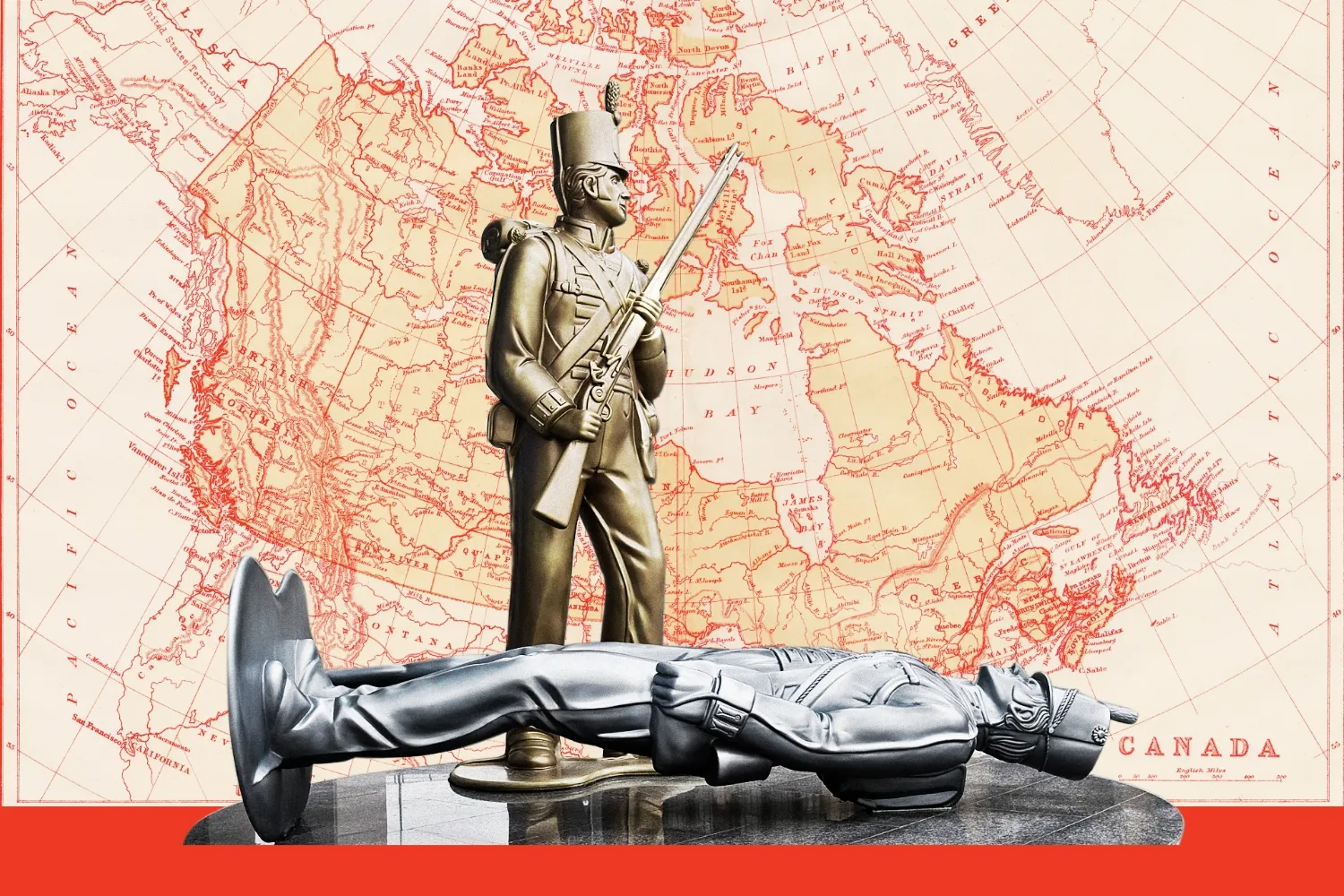

Foreign Policy illustration/Getty Images photos

As if U.S.-China relations weren’t complicated enough, the two sides are also squaring off over which side will lose face in their trade battle. In the United States, the Chinese concern about saving face is usually dismissed as pride—but U.S. President Donald Trump has made a career out of insisting that he get the upper hand in relations.

That’s a very Western form of face, according to scholars, who characterize it as the need for “honor” or individual triumph at the expense of someone else.

As if U.S.-China relations weren’t complicated enough, the two sides are also squaring off over which side will lose face in their trade battle. In the United States, the Chinese concern about saving face is usually dismissed as pride—but U.S. President Donald Trump has made a career out of insisting that he get the upper hand in relations.

That’s a very Western form of face, according to scholars, who characterize it as the need for “honor” or individual triumph at the expense of someone else.

“To really understand what’s going to happen [in the trade war] and how it will play out, you need a psychologist—not a policy analyst,” said Matthew Goodman, a former international economic official in the Obama administration who now works at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The struggle over face shows up most clearly in the tussle over who calls who first. Trump insists that Chinese President Xi Jinping initiate negotiations—and sometimes has suggested, without evidence, that he already has. That’s the opposite of the way that China usually operates; Chinese leaders rarely initiate contacts—or at least, they rarely admit to doing it. To do so would involve losing face.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent looks on as President Donald Trump signs executive orders in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington on April 9.Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Finding the right language to salve two prickly men is on the mind of the senior U.S. and Chinese officials who are scheduled to meet this weekend in Geneva, Switzerland. Few expect a breakthrough at the sessions between U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer, and Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng. In an interview with Fox News, Bessent sidestepped the question of who reached out first, saying that there were “a lot of contact points over time.”

The concept of face dates back to traditional Chinese hierarchical concepts of social relationships, said Ye Xue, a political scientist at the University of Alberta. The higher-status party in a relationship is owed deference, or face, from supplicants. In exchange, the superior is expected to act magnanimously and in the interests of the lower-status party. The theoretical goal, he writes, is a “harmonious hierarchy where everyone possesses face, with variations based on social status.”

Xue gives sixth-century philosopher Confucius credit for refining the system. Although the Chinese Communist Party has attacked Confucian thought at times, the hierarchical social structures that Confucians championed jibe with the party, where officials jockey for position by aligning themselves with those more powerful. Xi, the most powerful player of all, shows his magnanimity by appointing his acolytes to the ruling Politburo Standing Committee and other powerful positions.

The goal is supposed to be political harmony, although this environment often creates knives-out political battles where losers are jailed for corruption or otherwise humiliated and thus lose face. A case in point was Xi’s treatment of his predecessor Hu Jintao at the end of a Communist Party Congress in 2022, when a confused-looking Hu was escorted out of the hall while none of the members of the previous standing committee even dared to look at him.

In that way, too, Trump and Xi have a lot in common. Trump routinely forces members of his cabinet to sing his praises in televised meetings. Many of his former appointees have left with their reputations in tatters, and—in the case of former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and National Security Advisor John Bolton—their security protection removed.

Fear of seeming weak also interplays with domestic politics.

“The Chinese government is aware of how the Chinese population views how others treat them,” said Peter Gries, the director of the U.K.’s Manchester China Institute. “If Xi does something that makes him look weak, that applies to all of China and goes to regime legitimacy.”

A pro-China demonstrator steps on a defaced image of Nancy Pelosi during a protest against her visit to Taiwan outside the U.S. Consulate General in Hong Kong on Aug. 3, 2022.Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

Saving face doesn’t mean that Chinese leaders passively wait for others to initiate contact. They have many ways to signal their interest in talking without making a formal approach.

After China froze relations with the United States on a variety of issues in response to Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng used a meeting with senior Biden administration officials on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly meeting a month later to make clear that China wanted to resume high-level talks, said a former Biden official who was involved in the negotiations.

A spokesman at the Chinese embassy, where Xie is now ambassador, said that the Biden official’s recounting of the episode was that person’s “subjective inference” of what occurred.

Detailed negotiations ensued before President Joe Biden and Xi met in Bali two months later.

“It would be hard to describe how much time we spent in advance [of meetings with Chinese leaders], basically planning every single thing, how many steps people would walk, who would reach their hands out first in the greeting, who would raise particular issues in a discussion,” Biden’s Asia chief, Kurt Campbell, told CNBC in Hong Kong recently.

During the first Trump administration, the Chinese signaled in a different way. When trade talks fizzled out in 2019, the Chinese flagged that they wanted to try a new round of negotiations by suddenly unfreezing purchases of U.S. soybeans, according to a former Trump official.

But it’s important to China to be able to deny that it is initiating talks, as illustrated by a call between Chinese leader Jiang Zemin and Geoge W. Bush after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, at a time when the relationship was rocky.

Although Jiang called, U.S. the Wall Street Journal’s Lingling Wei noted, the Chinese readout said that Bush “made the request” for the call. A month later, Bush flew to Shanghai to meet with Jiang, another sign of respect, although the U.S. portrayed it differently.

“Rather than staying home, hunkered down, dealing with terrorism, he thought, ‘I’m going to get on the airplane, go to Shanghai, and show that America is still in business, is still a global power,’” said Bush’s national security advisor, Stephen Hadley.

But Trump has his own concern about image and face, perhaps stemming from the many years where he was dismissed as a real-estate developer who tried to use policy pronouncement to burnish his reputation. “To Trump, it’s not a win unless China comes to him,” said Jennifer Miller, a Dartmouth College historian who has studied Trump’s approach to trade.

U.S. President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump welcome Chinese President Xi Jinping and his wife Peng Liyuan to the Mar-a-Lago estate in West Palm Beach, Florida, on April 6, 2017.Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

That approach sometimes worked in Trump’s first administration. Then Xi courted Trump and consulted with Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe before meeting the U.S. president in Mar-a-Lago in April 2017. Abe had a reputation as a Trump whisperer who used flattery and bonhomie to strengthen U.S.-Japan relations.

In the run-up to the Mar-a-Lago summit, Xi dispensed with the intensive preparations that Chinese leaders usually insist on. Later in the year, Xi invited Trump to dine with him in the Forbidden City, a first for a U.S. president.

But after several rounds of what Trump calls “reciprocal” tariffs, Xi hasn’t bent to Trump’s insistence that he reach out first. Chinese officials fear that Trump could treat him with the kind of contempt that he displayed during his Oval Office session with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in February.

Trump’s unpredictability makes a meeting of the two leaders a gamble, and the Chinese aren’t gamblers when it comes to the image of their leaders. To make sure that Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg couldn’t get close enough to Xi to lobby him at an international conference in 2016 Chinese officials, for instance, China placed a phalanx of security guards between Xi, according to a book about Facebook written by a former company executive.

“I don’t think China is going to be prepared to really expose President Xi to high-level diplomacy with President Trump without appropriate preparation,” Campbell said.

Chinese-made cars are seen at the port in Nanjing, China, on April 16.AFP via Getty Images

China’s concern about face sometimes backfires. After Chinese troops fired at protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989, Beijing insisted falsely that no one had been killed—an attempt to save face that intensified international efforts to isolate China, said Gries, the Manchester China scholar.

More routinely, Beijing’s unwillingness to go first lets the Washington shape negotiations over trade, national security, and other matters, forcing the Chinese to play defense. And sometimes, the Chinese government insistence on face opens it to ridicule, such as when Beijing hit a Chinese comedy troupe was hit with a 14.7 million yuan ($2.03 million) fine in 2023 for making a joke about the military that referred to a slogan Xi used.

In the current trade fight, though, sitting back and waiting may give Beijing an advantage because it delays a resolution. Although Beijing’s economy is bound to be more hurt by high tariffs than Washington’s, because China is much more dependent on trade—already, export orders have started to slow—it is more politically insulated from popular discontent because it’s an autocracy. Beijing is betting that Trump feels the political heat of Americans irate at higher prices and empty shelves more intensely and immediately than the Chinese government feels economic heat from factory layoffs and missing markets.

Waiting also gives Beijing a chance to see what other countries offer Trump to get him to back off so it can better craft its eventual response.

“They may be running the clock,” said Daniel Bahar, a trade official in the first Trump administration who now works at Rock Creek Global Advisors, a Washington consulting firm. “That creates leverage with Trump because of the political pressure he faces at home, and it gives them more information about what he is doing with other trading partners.”

It also puts Xi in the position of the superior when it comes to face, meaning that he can then act with magnanimity if he chooses. The Chinese call that xiata, or “getting off the stage,” Gries said, which could translate to giving Trump a way to back off—in this case, by Beijing agreeing to trade talks.

There is some indication that Chinese officials are moving in that direction. China agreed to the Switzerland meeting, contending that the United States had requested the sessions. Although Washington didn’t eliminate tariffs first, as Beijing had wanted, the Commerce Ministry saved face by claiming that the United States had sent signals that it was considering reducing the tariffs and that China wouldn’t “sacrifice its principles” to get a deal

For his part, Trump said on May 7 that it was China that had blinked first. He said he wouldn’t slash tariffs to get China to negotiate, and he rejected the idea that Washington had asked for the Swiss talks.

“They said we initiated?” Trump said at a White House event. “Well, I think they ought to go back and study their files.”

U.S. President Donald Trump sits beside Chinese President Xi Jinping during a tour of the Forbidden City in Beijing on Nov. 8, 2017. Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

The United States is copying China’s handbook in its trade battles with other nations. After hitting India, Vietnam, Japan, and others with sky-high tariffs (albeit temporarily delayed ones), it is waiting for them to come to Washington with offers of trade concessions and investment pledges without giving any guidance of what would be enough to satisfy Trump.

“It’s a plausible negotiating strategy,” said Peter Harrell, a former Biden White House international economic official now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “See if we can get the other guy to negotiate against himself.”

Still, with both China and the United States insisting that the other side call first, there is no easy off-ramp. One longtime former U.S. national security official who I spoke to this week doubted that the Geneva meeting would lead to anything more than an agreement on how to hold future talks. Bessent, the Treasury secretary, told Fox News that he thought the Swiss talks would “be about de-escalation, not about the big trade deal.”

And even if Trump were to clearly back off and say that he wanted to give Xi a call, there is no guarantee Xi that would respond positively. After Washington shot down a Chinese high-altitude balloon that loitered over the United States in February 2023 and canceled the secretary of state’s visit to Beijing shortly thereafter, Beijing froze relations between the two countries.

Looking to quickly ease tensions, two weeks later, Biden said, “I expect to be speaking with President Xi”—making clear that he was the one who wanted to talk, as Chinese insistence on face required. It didn’t work.

It wasn’t until nine months later, during a summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, that the two leaders finally talked. And that only came about after several U.S. cabinet secretaries flew to Beijing to try to pave the way—a process that helped Beijing’s leaders save face.

Bob Davis is a reporter who covered U.S.-China economic relations for decades for the Wall Street Journal. He is the co-author of Superpower Showdown: How the Battle Between Trump and Xi Threatens a New Cold War. X: @bobdavis187

More from Foreign Policy

-

Eight people dressed in camouflage military combat uniforms wade across a river, the water up to their waists. The soldiers carry large backpacks along with their rifles. Snowcapped mountains and a thick forest of evergreen trees loom in the distance. Get Ready for the Aleutian Island Crisis

As conflict heats up in the Arctic, foreign adversaries eye Alaskan territory.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks to reporters before boarding Air Force One at Morristown Municipal Airport in Morristown, New Jersey, on April 27. Trump’s First 100 Days Reveal a ‘Strongman’s’ Unprecedented Weakness

No U.S. president has ever surrendered global power so quickly.

-

An elderly man and woman sit on the ground, the man on his knees as he sorts through something on the ground. Behind him are a rusted cart and bicycle in front of a paint-smeared concrete wall and a battered corrugated metal sign with the words USAID: From the American people” on it. What Trump’s New Budget Says About U.S. Foreign Policy

The president wants to significantly pull back on many of America’s traditional global engagements while spending more on the border and defense.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump listens to Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a cabinet meeting in the White House in Washington, D.C. Rubio’s Reorganization Plan Is a Wrecking Ball

The State Department revamp goes far beyond streamlining—it will devalue human rights and strip away critical expertise.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.