How World War II Changed the Global Economy

How World War II Changed the Global Economy

Industrial mobilization, high tax rates, and labor deals are part of the legacy.

Factory workers inspect silver cylinders on an assembly line in California during World War II. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

This week marked the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. Looking back, the war meant multiple things for the continent. It was, of course, an event of unprecedented violence and destruction. But it was also a moment of international cooperation, mobilization, and solidarity—and an economic watershed for the world.

How big of an economic event was World War II? Who were the winners and losers of the war’s economic redistributions? And was the war the world’s largest-scale industrial policy ever?

This week marked the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. Looking back, the war meant multiple things for the continent. It was, of course, an event of unprecedented violence and destruction. But it was also a moment of international cooperation, mobilization, and solidarity—and an economic watershed for the world.

How big of an economic event was World War II? Who were the winners and losers of the war’s economic redistributions? And was the war the world’s largest-scale industrial policy ever?

Those are just a few of the questions that came up in my recent conversation with FP economics columnist Adam Tooze on the podcast we co-host, Ones and Tooze. What follows is an excerpt, edited for length and clarity. For the full conversation, look for Ones and Tooze wherever you get your podcasts. And check out Adam’s Substack newsletter.

Cameron Abadi: How big of an economic event was World War II?

Adam Tooze: I think this is a moment when really talking about quantity and size and scale is important because it was just very, very big. I think that’s the thing to say. And it’s important to say that also as a corrective because folks will have heard in recent years people talking about war economies. It’s very current right now to talk about the need for Europe to go onto a war footing in its war with Russia. There was quite a lot of talk in the U.S. about that as well in the Biden presidency. Former U.S. President Joe Biden is a child of the war. He really liked references to World War II. Around COVID, there was talk of a kind of war economic situation and a resetting of the social contract, like what happened after World War II, around climate.

And if you actually know the basic parameters of 20th-century economic history, all of that seems a little bit silly, to be honest, because the scale of the mobilization for total war in World War II was like nothing ever seen before. It’s quite unique historically. It starts with World War I, where government spending as a share of GDP—the share of GDP measure is itself a product of World War I. Like when you do things on this scale, you need something very big to compare something else very big to, and you end up with GDP, gross national product, as your measure. In World War I, that ratio hovered between 30, 40. For some combatant countries, it went as high as 50 percent in bad times. In World War II, that shifts up a gear, it’s 40 to 60 percent of GDP among the combatant countries. So more than half of everything that’s being produced is going to the war effort.

So just look out in front of you and imagine the material world divided into one part, which is what you get to keep for civilian life, and the rest goes into the war effort. It’s absolutely dramatic. And there was conscious learning between these two phases. Modern macroeconomic policy in the sense we understand it shifted, our entire understanding of what the economy is shifted under the impact of these two conflicts. And World War II was where that really came home. The Keynesian revolution in economics is really better understood as a total-war evolution in economics which culminated in World War II, and it was all about managing the aggregate flows of demand, of production, of supply of labor, of supply of raw materials, of currency, of how to mobilize populations, how to carve off huge slices of populations so that they can actually serve. You know, tens of millions of men are mobilized, and women as well, in the war effort. Overwhelmingly men, though; it’s worth emphasizing that. And then at the other end of the spectrum, radical programs for the mass starvation of populations. We’ll say a lot more about that when we talk about the Holocaust. Deliberate efforts of starvation, not accidental, but deliberate efforts of siege and starvation applied in, say, the case of the German invasion of the Soviet Union to 30 to 40 million inhabitants of the Soviet cities of the western Soviet Union. And then also another kind of radical vision of the economy that emerges from the war is guerrilla war, Mao Zedong’s people’s war in China, where land reform and revolutionary upheaval are directly coupled to war-making.

So we have war economies in World War II, which are like those experienced in Britain and the United States or Germany, where you have well-managed modern economies tuned to a high state of optimization, humming along, being managed in new ways. You have the strange limbo of places like France and Denmark, which are under German occupation, whose economies are running hot but are serving German purposes, and so people are getting rich through collaboration in various ways, whilst others are enslaved, hunted down, or in the actual resistance. And then you have China, Southeast Asia, parts of the eastern front where you have a war economy more like the situation in Syria in the last 10 years, where economic survival and war-making go hand in hand. Those with the guns have the food, those with the guns have the gold, the money that actually counts, and the economy is remade in the process of hand-to-hand combat and fighting. So all of this plays out in the context of this epic struggle, which ends in 1945.

CA: How about the role that casualties played? Obviously, the scale of those casualties was appalling, but how big of a dent did they really make?

AT: So World War II is overwhelmingly the largest modern war in terms of casualties. The figures for deaths run between 70 and 85 million. Roughly one-third of that is military deaths. So 21 to 25 million. The civilian death toll is 50 to 55 million. And then within the civilian death toll, about half is directly war-related and half is famine, war-related disease, what you might call excess deaths that happened during this period. And you can tell from the roughness here that this is not easy to estimate because, as I was saying just a minute ago, in the most violent scenarios of the war in China, in Southeast Asia, in the Soviet Union, the state collapses and regular data gathering is really hard to do. For people thinking about this in Britain and the United States, where many of our listeners are, and from the vantage point that we’re in now, this can seem a very long way away. It’s something you watch in a documentary and a film. But if you’re somebody of my age, in my later 50s now, born in the mid to late ’60s, even in Western Europe, this sense of fear and loss was omnipresent. Both my parents were bombed as little children.

And if you spent time, as I did, growing up in Germany, the impact of this war was everywhere. You couldn’t go to the swimming pool without seeing men whose bodies were torn apart by grenades and bursts of machine gun fire. This was in the early ’70s. Most of my teachers in high school and elementary school were war veterans. They had frostbite wounds that would bother them, you know, if the weather changed. If you look at a society like Germany, which is the westernmost society really badly affected by the war—and obviously the protagonist of the war that started this, and it’s Germany’s surrender that we’re commemorating—40 percent of the cohort of men born around 1920 lose their lives in the war. In the Soviet Union, the figures are more debated, but the casualties are even larger. If you’re a young man born just after World War I, the chances of making it into the second half of the 20th century are really pretty slight in the Soviet Union. The casualty figures for the Soviet Union are hotly disputed, but it could be 27 million people. Russian propagandists put it higher. That’s 14 percent of the pre-war population. So look around you, and every sixth person is dead. Obviously, and we will talk about this, the Jewish population of Europe suffers in percentage terms the highest casualties, but in absolute numbers, even in Poland and Belarus where the Holocaust was incredibly intense, the number of non-Jewish casualties is larger. Cities like Warsaw were effectively erased in the course of the war. There are famines, pandemics. This is not just the war of bombing and shooting. The Henan famine in China took 2 million lives, 3 million died in Bengal under British rule in India, 2 million at the end of the war in Vietnam as the Japanese occupation fails, and deliberate starvation took millions more in the Soviet Union.

But the thing about this is that for all of this—and I rehearsed these numbers deliberately just to give a sense of the scale—this was still a modern war. So the majority of the casualties in that, shall we say, 75 million number, the majority are deliberate. About 50 million are deliberate. Only, quote unquote, 20 million are the result of famine and disease. So this is not a war like the wars of the 17th century in Europe, or the great global crisis of the 17th century, the Thirty Years’ War for instance, where you really do have military campaigns which are much smaller in scale than World War II but unleash state failure, which ultimately claim far more lives because they’re such poor societies and they’re also being ravaged by the plague, which is sweeping across Eurasia. So it’s not uncommon in the 17th century to see German regions losing not 3 percent of their population or 10 percent or 40 percent of one cohort, but 40 percent of their entire population dying. The population actually shrinks and doesn’t recover in much of Germany in the 17th century until the 18th century. Absolutely nothing like that in the 20th century. So of the 2 billion-odd people alive in the late 1930s, 3 percent die in the early 1940s. And by 1950, the global population is at 2.5 billion and set for the most explosive growth we’ve ever seen in the history of our species.

So this is this weird kind of duality about World War II. It’s, on the one hand, clearly the most explosively violent thing, combining these giant military campaigns, the Holocaust, settler colonial projects on a huge scale and the atomic bomb, all that on the one hand. And on the other hand, when you look at global demography, much less impactful than the general crisis of the 17th century, in part because we’ve gotten so good at managing, collectively, these struggles. It blows my mind that I was born only 22 years after the end of this conflict. As a kid, you just take it for granted, but that’s the age of the people I teach at Columbia. It’s that close, and it’s this kind of a controlled explosion of an absolutely extraordinary intensity.

CA: So in economic terms, who would we say the winners and losers of this major economic and social redistribution are?

AT: Again, I think your distinction between the controlled total war and the chaotic total war really is helpful here in that if you look at the controlled cases, and say you take the long-running data on inequality that, say, the famous team around Thomas Piketty in Paris put together, there’s no question that beginning with World War I, but then with World war II for real, the era of the total wars is the era that American labor economists call the great compression. So it’s a period in which inequality in income decreases very dramatically and inequality in wealth to a degree as well.

And you could take this as a sort of social bargain-type of argument, right? If you’re going to run total wars and you’re going to hold society together, which is exactly the hallmark of World War II in Western Europe and North America, then you are going to make big societal bargains, you’re going to renegotiate the social contract. And you’re going to do that by avoiding strikes, by making wage concessions to crucial workers through trade unions, and you are going to amplify welfare spending, and you are going to pay for this and you’re going to control excessive demand and inflation by imposing punitive taxation on highest incomes. And so, most societies exit World War II with marginal tax rates for the top 1 percent well in excess of 50 percent and then closer to 80 percent, even in the United States, through to the late 1950s. And that’s part of this deal. And it shows up in the data. This is the moment of the famous Treaty of Detroit where the American auto industry, the bastion of mass manufacturing, in the aftermath of the war, signs a formal accord with the Auto Workers Union agreeing to the terms and conditions of a privatized welfare state for American workers. We see the breakthrough of labor in Britain with the trade unions having played a key role in managing the home front in World War II. Ernest Bevin, Transport and General Workers’ Union boss and a pivotal figure in the wartime administration, and then foreign secretary, literally running foreign policy for the Attlee government after ’45, a union boss. That era is one in which indeed there is a huge shift.

But this is the virtue, then, of how illuminating it is to think in terms of this contrast between organized total war and chaotic total war. The aim of the game is, of course, to prevent revolutionary challenge. And so World War I ends with revolutionary upsurge practically everywhere after 1917, even for heaven’s sake in Britain and the United States. There’s a vast surge of general strike activity. There’s the Red Scare for a reason, in a sense, in 1919 in the U.S., right? Much of it is cooked up, but nevertheless, there really is a militant mobilization. And there is, of course, also revolutionary pressure in Europe, Western Europe, notably after 1945, but it’s much more contained. It’s channeled through trade unions. It’s channeled through the communist parties, which themselves have undergone Stalinization since the 1920s. And so it’s a much more concerted, controlled situation. And it’s not by accident that the revolutionary upheaval after World War II is not in Europe—though there is civil war in Italy effectively at the end and civil war in France, but in both cases, it’s a contained struggle. It’s in Asia where we really see full-on revolutionary struggle playing out with such dramatic consequences in China, in Vietnam, in Korea, in Malaya. There’s the free-for-all, which isn’t really frozen back into place in Asia until the ’60s, maybe if you take China and the Cultural Revolution then not until the ’70s.

So that’s, I think, the crucial thing to bear in mind, that the European and American progress of labor is manifest. You see it in the numbers. You can see it from space. It’s huge, there is a big shift, but it’s on the condition that we all agree to play by the rules of a modified version of the status quo.

CA: Does World War II basically amount to the biggest industrial policy ever, and, if so, what were the long-run effects of that policy?

AT: Really, World War I is the moment that opens the minds of people to the possibilities of concerted industrial programming of planning. World War I is the moment when Lenin, looking at the German war economy, goes, Oh, this whole planned economy socialist thing, we could actually do it. And then communism is Soviets plus electrification, right? Electrification being the industrialization part. And then in the ’30s, of course, you get the Stalinist experiment, which to describe that as industrial policy really does, I think, sort of undersell what’s going on. It’s industrialization by means of social revolution. But around the world, we see nationalist regimes in the ’20s and ’30s experimenting with efforts to build steel plants, to build cement capacity, to build railways, to build infrastructure in a massive way.

And World War II takes this all to a new level. There’s a degree, even, of preparatory pre-building for the war. So not just rearmament, as in the German case, like build me as many aircraft as possible, but the British build these shadow factories where they create what will be a facility for making Spitfires if the worst case happens, right? So it’s sort of a pre-planned expansion that you could operationalize. And so broadly speaking, yes, it’s a huge, transformative process. The Californian economy is transformed by the aerospace revolution of World War II, because the big expensive thing in World War II armaments is aircraft. If the iconic image of World War I is a shell factory, the iconic image of industrial production in World War II is aircraft. For good reason, because in the countries which go heavy on strategic bombing, 40 to 45 percent of the total war effort is aircraft. Everything else is tiny by comparison. And building those facilities on the West Coast of the United States transforms the Californian economy into the postwar period.

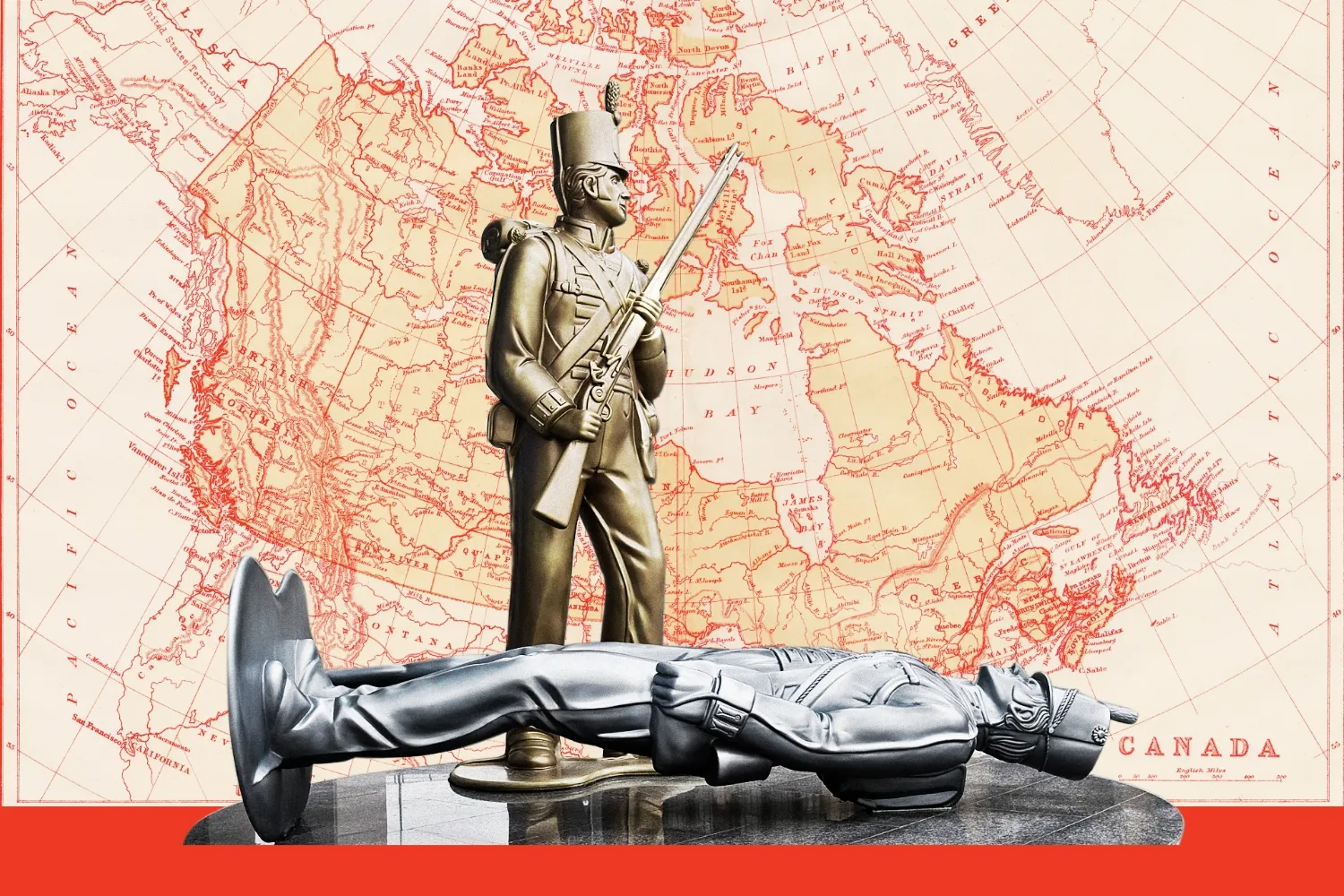

But it also reconfigures the Canadian-American relationship. The North American manufacturing complex in the Midwest that bolts onto Canada, it’s not really the Midwest, it’s really the Great Lakes region, right? The Michigan-Windsor connection is built during World War II because the aluminum is made on the Canadian side and then imported into the American industrial complex. And because this is the war time and the Canadians are part of the British Empire and running on Lend-Lease, there is this direct connection between the Canadian and U.S. economies, which is built out to an extent never seen before. And there’s no question, I think, that much of the dynamism of the West German economy after 1945 comes from the expertise that builds up during the mass production of weapons during World War II. Huge parts of the infrastructure of Eastern Europe are inherited from wartime industrialization, despite the devastation.

This post appeared in the FP Weekend newsletter, a weekly showcase of book reviews, deep dives, and features. Sign up here.

Cameron Abadi is a deputy editor at Foreign Policy. X: @CameronAbadi

Adam Tooze is a columnist at Foreign Policy and a history professor and the director of the European Institute at Columbia University. He is the author of Chartbook, a newsletter on economics, geopolitics, and history. X: @adam_tooze

More from Foreign Policy

-

Eight people dressed in camouflage military combat uniforms wade across a river, the water up to their waists. The soldiers carry large backpacks along with their rifles. Snowcapped mountains and a thick forest of evergreen trees loom in the distance. Get Ready for the Aleutian Island Crisis

As conflict heats up in the Arctic, foreign adversaries eye Alaskan territory.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks to reporters before boarding Air Force One at Morristown Municipal Airport in Morristown, New Jersey, on April 27. Trump’s First 100 Days Reveal a ‘Strongman’s’ Unprecedented Weakness

No U.S. president has ever surrendered global power so quickly.

-

An elderly man and woman sit on the ground, the man on his knees as he sorts through something on the ground. Behind him are a rusted cart and bicycle in front of a paint-smeared concrete wall and a battered corrugated metal sign with the words USAID: From the American people” on it. What Trump’s New Budget Says About U.S. Foreign Policy

The president wants to significantly pull back on many of America’s traditional global engagements while spending more on the border and defense.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump listens to Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a cabinet meeting in the White House in Washington, D.C. Rubio’s Reorganization Plan Is a Wrecking Ball

The State Department revamp goes far beyond streamlining—it will devalue human rights and strip away critical expertise.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.