China’s J-10 ‘Dragon’ shows teeth in India-Pakistan combat debut

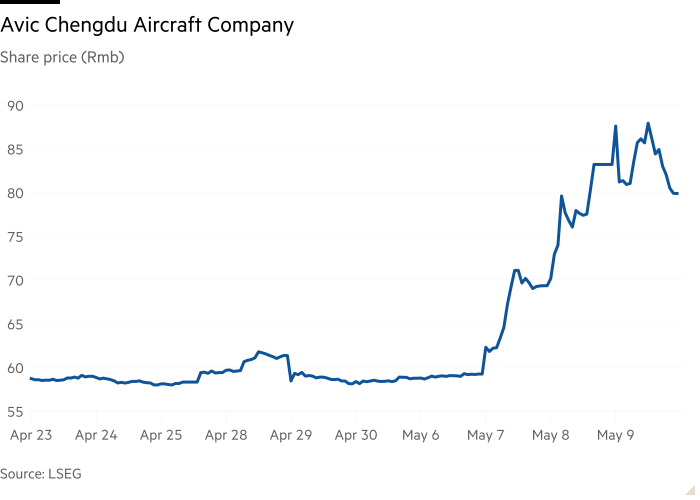

Even before the fog of war had begun to lift, the Chengdu Aircraft Company’s stock had started to soar.

Almost three decades after first taking to the skies, the Chinese plane-maker’s first fighter jet, the J-10 Vigorous Dragon, had finally seen combat — and survived.

By 4am on May 7, Chinese diplomats in Islamabad were at the foreign ministry, poring over results from the first face-off between modern Chinese warplanes, replete with missiles and radars untested in battle, and advanced western hardware deployed by India.

As evidence mounted, while remaining inconclusive, that a Pakistani pilot in the latest variant of the Vigorous Dragon may have shot down India’s French-made Rafale jet, Chengdu’s share price leapt more than 40 per cent in just two days.

“There’s no better advertisement than a real combat situation,” said Yun Sun, a specialist in Chinese military affairs at the Stimson Center in Washington DC. “This came as a pleasant surprise for China . . . the result is quite striking.”

While India and Pakistan may be embroiled in their deepest skirmish in decades, the conflict is also a testing ground for equipment crucial to a different rivalry — that between China and the US-led western alliance.

About 81 per cent of Pakistan’s military equipment comes from China, including more than half its 400-strong fighter and ground attack aircraft, according to estimates by the Stockholm Peace Research Institute and the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

That reflects an “all weather friendship” that China has cultivated since the 1960s with Pakistan to try and ringfence India. The materiel it provides Pakistan has evolved alongside China’s own defence industry, said Andrew Small, an expert on Pakistan-China relations at the German Marshall Foundation.

“Aside from the co-operation on nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, a lot of what China supplied used to be low-end stuff — tanks, artillery, small arms,” said Small. Now, however, Pakistan “is becoming a showcase for some of China’s newer capabilities”.

India, meanwhile, has emerged as the world’s largest weapons importer as its wealth and regional ambitions have grown.

Over the past decade, it has shifted from a reliance on Russian suppliers to the US, France and Israel for almost half of its own recent purchases, including sophisticated fighter jets, transport aircraft and combat and surveillance drones.

“This is the most important global aspect here — this is the first time Chinese military equipment has been tested against top notch western equipment,” said Sushant Singh, lecturer at South Asian Studies at Yale University.

“Whenever and however this ends, the balance sheet will tell us what will happen in Taiwan, and which direction should western defence companies go to counter the low cost and high tech capabilities that the Chinese have shown.”

When countries go to war, their allies watch and learn. After Ukraine repelled a nearly 50-mile column of Russian armour — tanks, armoured vehicles and others — using modern, shoulder-fired British and American missiles, Indian diplomats in Kyiv were monitoring it closely.

“Is it true what they say about Russian tanks — clumsy, easily lolly-popped,” one asked an FT journalist returning from the frontline, referring to how missiles would blow the tops off tanks.

When Taiwan saw how effective the US-made Himars medium-range precision missile system was at hitting Russian targets behind the frontline, it lobbied to move up the delivery of its own orders. By next year, it will own almost 30 of the truck-mounted systems — which is more than Ukraine.

Even short skirmishes, such as those India and Pakistan have regularly fought, serve a unique purpose. Enemies test each other, and show off their own capabilities, seeking to enforce existing red lines and set new ones.

They generate vast amounts of operational data that shapes the next skirmish — or wins the next war. Allies share that data and arms manufacturers analyse it, tweaking their own weapons systems.

Defence attachés from China’s western rivals were waiting “impatiently”, said one in New Delhi, for India to share the radar and electronic signatures of the J-10C while in combat mode so that their own aerial defences could be trained on it.

Similarly for China, this skirmish was a test not just of the aircraft but the sophisticated radar system — called an active electronically scanned array — mounted in the front of the plane. The combat tested its ability to not just hunt out threats but help guide the missiles.

Aurangzeb Ahmed, Pakistan’s deputy chief of air operations, said PL-15 variants were among the missiles used in the skirmish this week. The hour-long engagement would be “studied in the classroom”, bragged Ahmed. “We knocked some sense into these guys.”

Robert Tollast, a researcher at the Royal United Services Institute in London, said the use of PL-15E missile could be “highly significant”. Indian media reported that an intact PL-15 had been recovered, providing a chance to study its secrets.

“If confirmed, we have now seen the demonstration of a Chinese-made AESA on a beyond-visual-range-missile, used in combat,” he said.

Western nations and Russia have been battle testing their versions of AESA’s for decades. Details of just this single skirmish — such as how many missiles were fired to successfully hit a target — “could be tremendously useful for the Chinese in evaluating the capability of this weapon”, Tollast said.

Neither the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, nor Chengdu Aircraft responded to a request for comment.

On the other side of the ledger, the success of Indian missiles — many of them reportedly long-range French SCALP missiles — in finding their targets showed both the weakness and paucity of Pakistani aerial defences.

Pakistan is known to deploy China’s HQ-9 systems, which are a generation behind the sophistication of Russian S-400s and are at the top-end of India’s inventory.

“The fact is that even at a time of extreme high alert, Indian missiles penetrated Pakistani airspace without being detected,” said Laxman Kumar Behera, who specialises on India’s national security at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

India’s retaliation on Thursday targeted Pakistan’s “air defence radars and systems at a number of locations in Pakistan”, according to the Indian military.

“That’s a very precise display of a very high-end capability — taking out the defences, rather than an actual target,” said a senior western diplomat based in Delhi. “It’s a carefully calibrated warning — it says, look, if we can come take the lock off your door, then we can come into the house whenever we want.”

Both India and Pakistan have gleaned crucial details about their rival’s strengths from past clashes — and identified weaknesses of their own.

After India successfully wrested back territory in the Himalayas from a Pakistani encroachment in 1999, an internal inquiry showed its ageing Russian fleet of MiG’s struggled to manoeuvre in the mountain passes, or find targets in the snow while evading shoulder mounted missiles.

Three aircraft were shot down in three days before India switched to French Mirages — the first deployment of precision and laser guided missiles by the Indian Air Force, and the beginning of a shift away from Russian to western aircraft.

Similarly, after India responded to the 2019 killing of 40 security personnel by a Pakistan-based militant group with air strikes in the Balakot region of Pakistan, it not only lost a MiG 21 aircraft but its forces mistakenly shot down a helicopter in a friendly fire incident, killing seven.

“The officers of the Pakistani army have looked after me very well — they are thorough gentlemen,” the captured pilot was shown saying in a propaganda video before his release. “And the tea is fantastic.”

The two incidents underscored that India lacked sufficient airborne early warning and control systems — planes that fly at high altitudes carrying sophisticated radars and sensors that can detect enemy aircraft, missiles and drones at range.

But India’s bureaucratic challenges made learning from each skirmish difficult, and inefficient, as compared to a simpler procurement system for Pakistan, which has one main supplier — China — and a military that dominates the country.

Only in March this year did India issue an “acceptance of necessity” notice to triple India’s fleet of such early warning aircraft to 18. Their deployment is years away.

“If these tit-for-tat aerial retaliations continue for much longer, India will feel their absence sorely,” said a second western defence attaché based in New Delhi.

“If it turns out that India lost a French jet to a Chinese missile fired from over 100km away, then that need is clearly urgent.”