How Much Power Does the Aga Khan Have, Really?

Analysis

How Much Power Does the Aga Khan Have, Really?

The billionaire Muslim leader is a religious figure—and a global powerbroker.

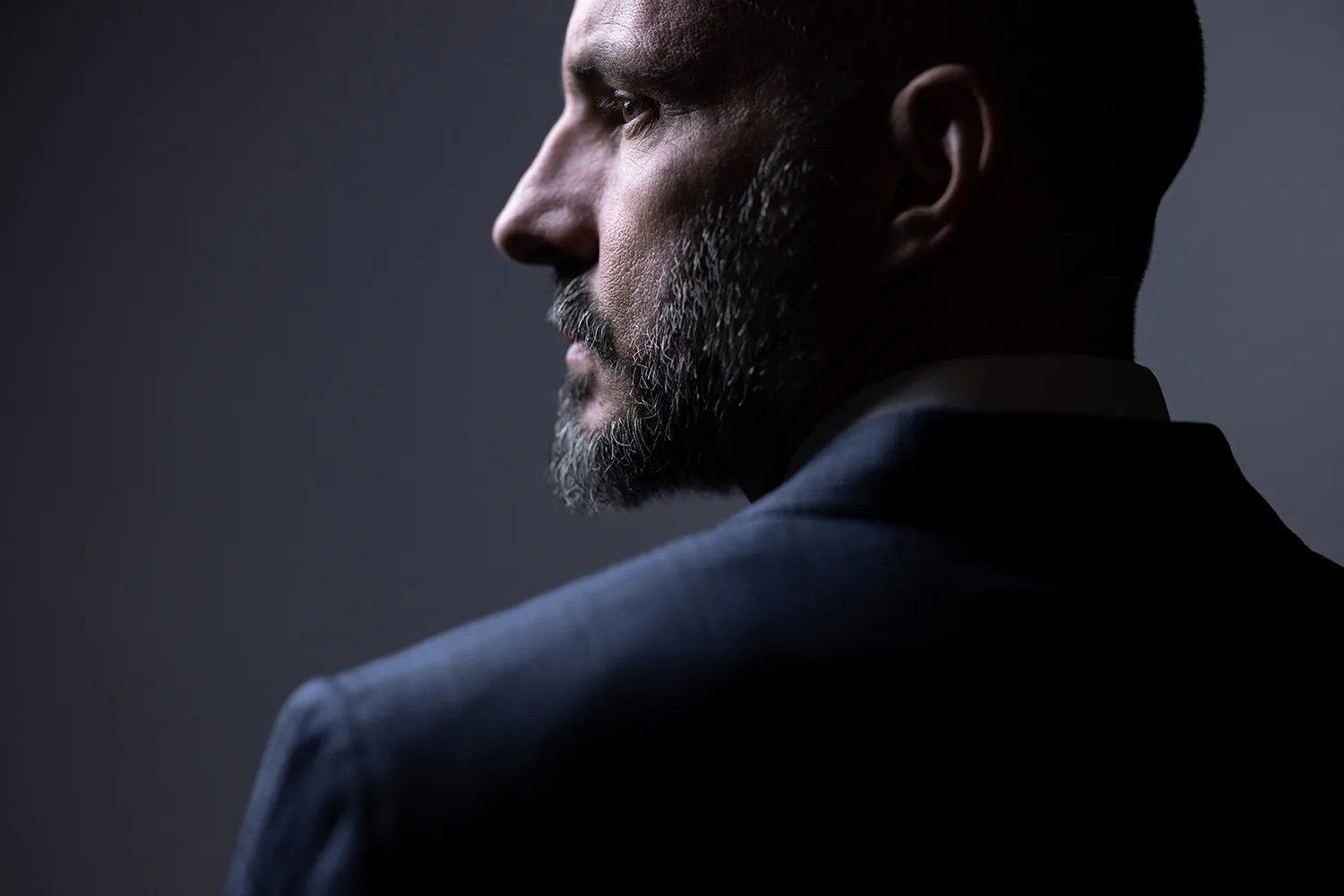

Prince Rahim Aga Khan V poses for a photo during the Paris Peace Forum on Nov. 10, 2023. Joel Saget/AFP via Getty Images

When international delegations attended the European Commission’s conference on Syria on March 17, Prince Rahim Al-Hussaini, or Aga Khan V, attended alongside them. Addressing the conference, he reiterated his community’s more than millennium-long history in Syria and recommitted the Ismaili Imamat and its development arm, the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), to “ongoing and permanent support for the Syrian people” and a “determination to help foster peace, hope, and development for a better future.”

The conference, and the pledge, was one of the first prominent public moves for Prince Rahim, who inherited the Aga Khan title from his father, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, who died on Feb. 4. The fourth Aga Khan served as leader of the Nizari Ismaili—or simply Ismaili—community, the second-largest branch of Shiite Muslims, since 1957. As Aga Khan IV’s eldest son, Prince Rahim now leads an estimated 12 to 15 million Ismaili Muslims across more than 35 countries.

When international delegations attended the European Commission’s conference on Syria on March 17, Prince Rahim Al-Hussaini, or Aga Khan V, attended alongside them. Addressing the conference, he reiterated his community’s more than millennium-long history in Syria and recommitted the Ismaili Imamat and its development arm, the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), to “ongoing and permanent support for the Syrian people” and a “determination to help foster peace, hope, and development for a better future.”

The conference, and the pledge, was one of the first prominent public moves for Prince Rahim, who inherited the Aga Khan title from his father, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, who died on Feb. 4. The fourth Aga Khan served as leader of the Nizari Ismaili—or simply Ismaili—community, the second-largest branch of Shiite Muslims, since 1957. As Aga Khan IV’s eldest son, Prince Rahim now leads an estimated 12 to 15 million Ismaili Muslims across more than 35 countries.

Considered a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, the Aga Khan is, first and foremost, a religious leader. But over the last 100 years, the role has also been a consistent, and significant, presence in global affairs.

A depiction of the first Aga Khan, circa 1818.Brittanica

Though under 1 percent of the global Muslim population, Ismailis have wielded substantial political authority and remain an intellectually influential minority, religion professor Khalil Andani told Foreign Policy. Referencing the famed Iranian American scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Andani said “there is hardly an aspect of Islam, especially in its earlier development, which was not influenced in one way or another by Ismailism.”

Shiites, around 10 percent of the global Muslim population, maintain that the Prophet Muhammad’s family are Islamic tradition’s sole, genuine interpreters. Ismailis look to a particular 1,400-year succession line to establish and legitimize imams, whom they rely on for spiritual guidance as divinely appointed leaders.

The title of Aga Khan, “chief of chiefs” or “chief commander,” was granted to the 46th hereditary imam Prince Hasan Ali Shah, by the shah of Persia in 1817. As Aga Khan, the imam is seen as the absolute authority governing Islamic beliefs, practice, and ethics for his murids—oath-bound followers—and matters related to their tithes, marriages, divorces, and community leadership.

The first Aga Khan received the title from the Shah of Persia in the early 19th century, before being appointed governor of Iran’s Kerman province. His influence expanded in conjunction with the British to Afghanistan and Pakistan’s Sindh province. In 1866, the British Raj, having already relied on the Aga Khan’s services in Sindh’s annexation in 1843 and noted his influence and charismatic influence among the Khojas in then-Bombay, India, established his authority in the “Aga Khan case.” The first Aga Khan’s eldest son, Aqa Ali Shah, became Aga Khan II. A member of the Iranian royal family by marriage, he maintained close ties with the British colonial government and became a significant leader for Muslims across the Indian subcontinent.

The Aga Khan III and his horse at Longchamp Racecourse in Paris in 1948. Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Then, in 1885, at the age of 7, Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah inherited the imamat from his father and became Aga Khan III. Later studying at prestigious British institutions, he effortlessly moved through circles of royalty, intellectuals, and the global elite, having also married into Europe’s privileged classes. Once described as a Muslim pope, Aga Khan III helped found the All-India Muslim League political party in 1906 to advance the interests and protection of British India’s 80 million Muslims. He served as its first president until 1912, and in 1932, he represented India at the League of Nations and became president of its 18th assembly from 1937 to 1938.

Aga Khan III also developed a reputation as a simultaneous spiritual leader, pleasure seeker, and political luminary belonging to no person or nation, a personage he passed on to his grandson and successor, Aga Khan IV. A similarly transnational figure, Aga Khan IV was a jet setter who influenced global politics until his death. Along the way, he developed a reputation as an international playboy, leading a lavish lifestyle that included ownership of a nearly $25 million super-yacht and a private island in the Bahamas.

Clockwise from top left: Aga Khan IV with his wife, Begum Salimah, during their wedding in Paris in 1969; during a ski trip in Austria in 1957; arriving at a ball in Monaco in 1978, and at a horse race in Saint-Cloud, France, in 1961.

The family’s wealth is estimated somewhere between $800 million and $13 billion, sourced from inherited funds, real estate and tourism investments, and a widely known horse-breeding business. The Ismaili Imamat insists that the Aga Khan’s personal wealth is not derived from zakat (the religious obligation to donate to charity) from its worldwide membership. While zakat is one of the five pillars of Muslim faith, encouraging the donation of 2.5 percent of one’s annual net worth, Ismailis give what they call a dasond, meaning one-tenth, which is between 10 to 12.5 percent of their net income. These contributions, the imamat maintains, are used exclusively for the community’s needs, investments, and expenses.

The fourth Aga Khan also used his money and influence for his community’s benefit, even if his role was less overtly political compared to prior Aga Khans, according to Andani. The late Aga Khan IV articulated his mandate as extending beyond the community’s spiritual welfare to its physical well-being and security, becoming one of the world’s leaders in development, educational, and health care philanthropy. This was largely under the auspices of the AKDN, which deals with a wide range of development issues. The network’s expansive reach includes hospitals, farming initiatives, schools, clinics, museums, centers, and Aga Khan Universities.

The AKDN employs 96,000 people to provide services through 1,000 programs and services in more than 30 countries. Despite the Aga Khan’s official apolitical stance, his soft power is immense.

A crowd of Ismailis gathers for the enthronement of Prince Karim Aga Khan in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on Oct. 20, 1957, following the death of his grandfather Aga Khan III. Intercontinentale/AFP via Getty Images

Shariq Siddiqui, director of the Muslim Philanthropy Initiative at Indiana University in Indianapolis, said the Aga Khan’s far-reaching resources foster a certain kind of presence. “All philanthropy is a form of influence, right?” Siddiqui said. “When you want to make the world a better place, you use your resources to help and show that you care, that you are an instrument of good within the larger society.”

To that end, the Aga Khan is one of few leaders without territorial rule who is afforded state honors. And the Ismaili Imamat—as an institution—has been recognized as a legal personality in several countries. The role is “a quiet, very practical form of diplomacy,” Andani said.

What sets the AKDN apart, perhaps, is its ability to harness and channel its wealth paid by Ismailis across the globe toward a centralized, systematic force, enabling the AKDN to put Islamic practice to use in the neoliberal world order, Siddiqui said.

Ancient faith combined with contemporary zeitgeist is central to current Ismaili influence and why the Aga Khan is invited to contribute in word and deed to nations’ development. According to Canadian scholar Mohammad N. Miraly’s book Faith and World: Contemporary Ismaili Social and Political Thought, contemporary Ismaili philosophy can frame liberal values like democracy, pluralism, philanthropy, and education as contemporary expressions of their interpretation of eternal Quranic principles and the binding teachings of Shiite imams. Throughout his nearly seven decades of leadership, Aga Khan IV frequently articulated the principles of liberal democratic pluralism as the best means to realize his dual mandate to improve the spiritual and material lives of his followers and their societies.

Additionally, Aga Khan IV believed institutionalizing modern liberal values within the imamat and through the AKDN was part and parcel of ethical Islamic living in the 20th and 21st centuries. Frequently, he reiterated how the “cosmopolitan ethic” of Islam guided his activities. As such, the AKDN became an practical, institutional vehicle to make manifest Ismailis’ beliefs and Islam’s fundamental ethics, as espoused in its ethical framework: compassion, generosity, inclusiveness, sound mind, knowledge, and discovery. Consequently, the Aga Khan frequently bemoaned the rise of extremism and intolerance and worked to encourage pluralism through the establishment the Global Centre for Pluralism in Ottawa, Ontario, in 2017.

Even so, the Aga Khan and AKDN works with people from multiple backgrounds to ensure the safety of Ismailis and their communities, said Ayso Milikbekov, who has worked in development with the AKDN in Kenya and Central Asia. “Democratic or authoritarian governments and nations, it doesn’t matter,” he told Foreign Policy. For example, the AKDN was one of the few international organizations that kept its operations going after the Taliban regained power in Afghanistan in 2021. Ismailis are a small minority in the country and the AKDN has invested millions in large-scale rural development since 2002. “The goal is to find and promote peace,” said Milikbekov. “Then you can approach other matters of extremism, economics, politics, culture, etc.”

A large crowd of Ismailis pray as they wait for the Aga Khan IV to arrive leader to arrive in Tajikistan on Sept. 25, 1998. Richard Wayman/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images

In Tajikistan, where civil war broke out in 1992 after the mainly Ismaili population of the Gorno-Badakhshan autonomous region declared independence, the Aga Khan provided food and aid, wielding his authority and resources to help end the conflict.

As Georgetown scholar Shenila Khoja-Moolji’s research shows, the Aga Khan’s leadership inspires Ismailis the world over to rebuild their lives and communities following displacement, forced migration, and persecution. Altogether, this can make the Aga Khan a bit of a curiosity at a time when religion and religious people can be sidelined as conservative forces leading toward intolerance, rather than working for the “secular” good.

At the same time, the modern globalized context and its concomitant liberal state apparatus seem to provide prime space for Ismailism’s particular interpretation of Islam, leading to what anthropologist Jonah Steinberg called its “phoenix-like renaissance” over the last 100 years. For example, in Canada, where nearly 80,000 Ismailis live, the religion has thrived, and members represent the most elite levels of business, culture, and politics. In 2008, the Aga Khan established a Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat, a de facto embassy in the Canadian capital. In 2009, he became the fifth person to gain honorary Canadian citizenship.

Aga Khan V, right, adjusts his tie during a meeting in Lisbon on Feb. 13. Rodrigo Antunes/Reuters

With its supra-national structure, multiple international and local councils, and, since 2015, official seat in Lisbon, Portugal, the Ismaili Imamat sometimes operates more like a transnational corporation than a state or a religious community. The AKDN pursues its work for the benefit of its international membership, regardless of the government in power and without concern for the eventual political outcome. Thus, the Aga Khan’s political role can seem more like that of a well-connected, well-respected businessman than a national leader or intergovernmental organization. However, that character might be what makes Ismailism, and the Aga Khan, so powerful—and perhaps the embodiment a future where organizations and entities beyond the nation-state will play an ever-greater role in international affairs.

As Prince Rahim steps more fully into his father’s vacated role, the question remains how he will be able to wield the title’s “integral presence” in the years to come. His appearance in Brussels was surely just a start. But it was also continuing a hundred-plus-year legacy, said Andani. “We expect the new Aga Khan to continue his father’s modus operandi,” he said. “We expect him to be a great example of how ancient theological ideas and philosophical principles can be enacted for the practical benefit of people all over the world today.”

This post appeared in the FP Weekend newsletter, a weekly showcase of book reviews, deep dives, and features. Sign up here.

Ken Chitwood is a religion scholar and reporter based in Germany.

More from Foreign Policy

-

Indian Air Force personnel stand in front of a Rafale fighter jet during a military aviation exhibition at the Yelahanka Air Force Station in Bengaluru. A Tale of Four Fighter Jets

The aircraft India and Pakistan use to strike each other tell a story of key geopolitical shifts.

-

A cardinal in a black robe with red sash with hands folded in front of him walks past a stage and steps. Conclave Sends Message With American Pope

Some cardinals had been agitating for U.S. leadership to counter Trump.

-

An illustration shows red tape lines crossing over and entrapping a semiconductor chip. Is It Too Late to Slow China’s AI Development?

The U.S. has been trying to keep its technological lead through export restrictions, but China is closing the gap.

-

A man watches a news program about Chinese military drills surrounding Taiwan, on a giant screen outside a shopping mall in Beijing on Oct. 14, 2024. The Pentagon Fixates on War Over Taiwan

While U.S. military leaders fret about China, Trump has dismissed the Asia-Pacific.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.