Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs Get Struck Down in Court

Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs Get Struck Down in Court

But the administration has other ways to build protectionist walls that are less vulnerable to legal challenges.

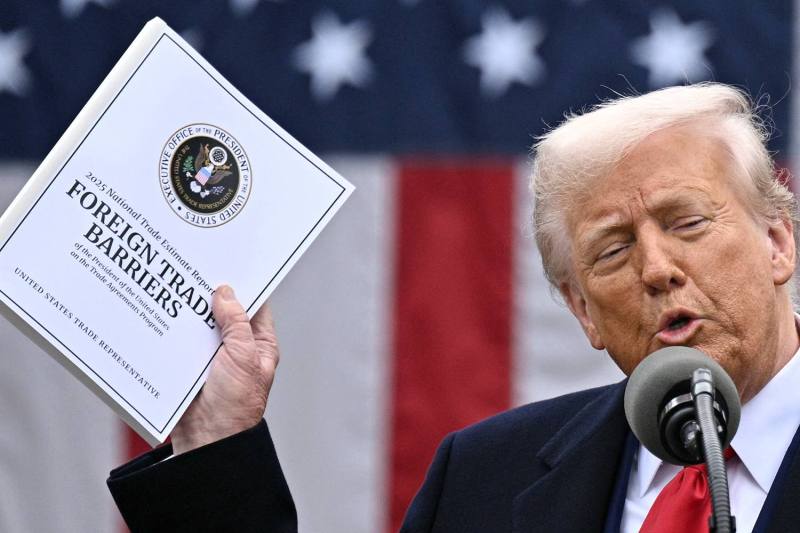

U.S. President Donald Trump delivers remarks on tariffs at the White House in Washington on April 2. Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

On May 28, a U.S. federal court struck down the Trump administration’s sweeping “Liberation Day” tariffs on the rest of the world, as well as the fentanyl-related tariffs on China, Canada, and Mexico, delivering a significant yet certainly not definitive setback to President Donald Trump’s trade agenda.

The U.S. Court of International Trade ruled that the tariffs represented an unconstitutional power grab of congressional trade authority, after Trump invoked Carter-era legislation to impose, for the first time ever, hefty tariffs on global trade.

On May 28, a U.S. federal court struck down the Trump administration’s sweeping “Liberation Day” tariffs on the rest of the world, as well as the fentanyl-related tariffs on China, Canada, and Mexico, delivering a significant yet certainly not definitive setback to President Donald Trump’s trade agenda.

The U.S. Court of International Trade ruled that the tariffs represented an unconstitutional power grab of congressional trade authority, after Trump invoked Carter-era legislation to impose, for the first time ever, hefty tariffs on global trade.

The ruling doesn’t mean that Trump’s war on trade is dead, merely that it is in a different kind of limbo from the one he brings about himself with on-again, off-again delays and reversals of his own stated trade policies. The Trump administration immediately appealed the ruling, and a higher court may well overturn the decision. The tariffs, which are at different rates for different countries, remain in place for now.

“The court’s decision is a big deal, and I am not entirely sure how this will play out. Courts have been exceedingly deferential to executive branch emergency and national security claims,” said Clark Packard, a trade expert at the Cato Institute in Washington.

Even if the ruling survives on appeal—and the Nixon administration weathered an initial reverse before winning on appeal after doing smaller-scale tariffs under a law prior to the one Trump invoked—the administration has plenty of other options. Over the decades, Congress has delegated a host of trade authorities to the executive branch, many of which Trump has already used and may well again. That means that U.S. trade partners overseas, who are currently figuring out whether to appease Trump or resist him, still have months of uncertainty ahead.

“No one is out of the woods yet,” said Mona Paulsen, a trade expert at the London School of Economics. “This is really about limiting” the tariff authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the 1977 legislation that Trump used to justify sweeping tariffs on every country in the world (and some that aren’t).

“The ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs could still get done under other authorities,” Paulsen said.

The case was brought before the Court of International Trade by a group of U.S. businesses and states who took aim at both the fentanyl tariffs and the global import duties that Trump initially levied in early April. (He partially paused most of them while negotiating “trade deals” with the rest of the world.) The issue was whether the president has the right to declare unrelated “national emergencies” and then impose whatever import duties he sees fit. The court, at least, had it clear.

“The court does not read IEEPA to confer such unbounded authority and sets aside the challenged tariffs imposed thereunder,” the ruling stated.

There are all sorts of interesting implications in the ruling, including examining the extent to which IEEPA was meant to circumscribe the very authority that former President Richard Nixon had cited when he shocked the world with unilateral tariffs in 1971 by invoking a World War I-era law.

The court believed that IEEPA does, in fact, specify some limits on presidential authority, especially when it comes to creating trade policy, constitutionally the sole purview of Congress. Merely declaring a “national emergency,” as the Trump administration did with the alleged fentanyl crisis at the Canadian border or the existence of goods trade deficits with various countries, is not carte blanche; or, as the ruling put it, IEEPA’s “Section 1701 is not a symbolic festoon; it is a ‘meaningful[] constrain[t] [on] the President’s discretion.’”

The ruling “is very much rooted in this question of how far Congress will delegate powers to the president,” Paulsen said. “Can the president impose unlimited tariffs? Here we have a very strong position from the court, when it comes to this particular legislation.”

Of course, the Trump administration might win on appeal, like the Nixon administration did. One big encouragement for free traders is that reversal recognized there were limits to presidential authority on tariffs, even under the more expansive 1917 legislation that Nixon used. The narrower IEEPA, coupled with vastly higher tariff rates under Trump, might give appeals courts pause this time.

But Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, as well as the duties on autos, pharmaceuticals, lumber, and copper, all rely on a more gold-plated authority, Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. Doing tariffs that way takes more time, and there are limits, but it can (and likely will) be done. Additionally, there are several other authorities, including another never-before-used trade provision from the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which seems to give the Trump administration the power to slap tariffs of up to 50 percent on any country for almost any reason.

“Section 338 [of the 1930 act] is still on the books, and it has never been used. It is extremely vague about what constitutes ‘trade discrimination,’” Paulsen said, but it allows expansive presidential authority to set import rates. Perhaps, she suggested, the court ruling will prompt Congress to reassert its trade authority, as it was urged to do an administration ago and tried half-heartedly to do earlier this year.

Still, even if the court ruling merely squeezes the Trump administration’s love of tariffs into a different balloon, there are positives to finally testing the limits of IEEPA, which has always been seen as potentially open to abuse from the executive branch, whether related to economic sanctions or trade barriers.

“I think it’s good the court put the brakes on a little bit. The other authorities take more time to implement and have greater guardrails, so [the ruling] somewhat minimizes the potential damage,” Packard said.

This post is part of FP’s ongoing coverage of the Trump administration. Follow along here.

Keith Johnson is a reporter at Foreign Policy covering geoeconomics and energy. Bluesky: @kfj-fp.bsky.social X: @KFJ_FP

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.