Hegseth Fails to Reassure Asian Allies at Shangri-La

Hegseth Fails to Reassure Asian Allies at Shangri-La

Confrontational rhetoric combined with uncertain commitments raise fears of abandonment in Southeast Asia.

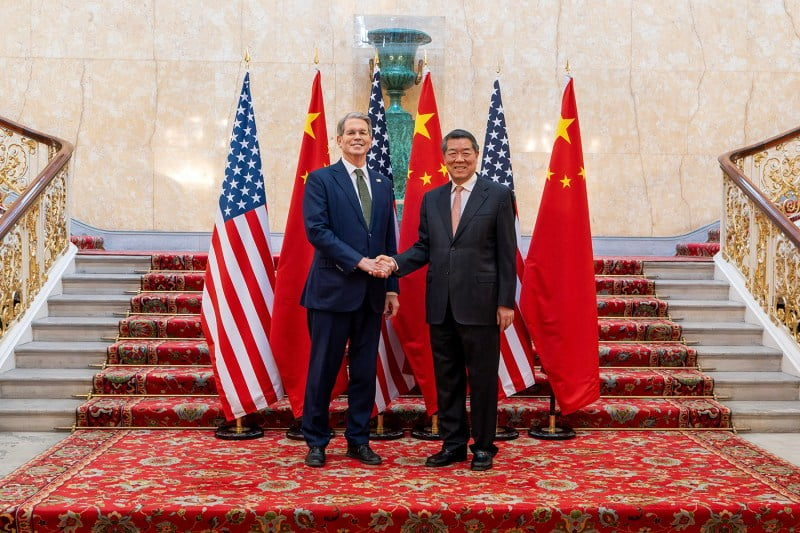

Shangri-La Dialogue attendees watch outside the ballroom as U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth speaks in Singapore on May 31. Mohd Rasfan/AFP via Getty Images

Onstage in Singapore on May 31 at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue defense forum, U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told Indo-Pacific leaders that the United States was “here to stay.” He went on to articulate a vision of the United States as an “Indo-Pacific nation” committed to reestablishing deterrence against China. But if the main goal of Hegseth’s address was to reassure Asian partners and allies questioning U.S. security commitments to the region, then the administration fell short.

Hegseth’s confident rhetoric belied a more uneasy reality. His speech accelerated a mismatch between U.S. promises to “pivot” to the Indo-Pacific and its consistent failure to deliver. Nowhere is this mismatch more evident than in Southeast Asia, where China continues to expand its influence.

Onstage in Singapore on May 31 at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue defense forum, U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told Indo-Pacific leaders that the United States was “here to stay.” He went on to articulate a vision of the United States as an “Indo-Pacific nation” committed to reestablishing deterrence against China. But if the main goal of Hegseth’s address was to reassure Asian partners and allies questioning U.S. security commitments to the region, then the administration fell short.

Hegseth’s confident rhetoric belied a more uneasy reality. His speech accelerated a mismatch between U.S. promises to “pivot” to the Indo-Pacific and its consistent failure to deliver. Nowhere is this mismatch more evident than in Southeast Asia, where China continues to expand its influence.

The result is a widening gap between the United States and its partners. Singaporean Defense Minister Ng Eng Hen recently described the United States as a “landlord seeking rent.” Others have been less blunt but equally clear. During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Kuala Lumpur in April, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim said that “some nations abandon the principle of shared responsibility and others question long-standing commitments,” while “China’s global initiatives offer a new lease on hope.”

Regional leaders want a committed, stable Washington that can counterbalance China but not escalate tensions further. The vision that Hegseth presented, however, makes clear that this option is no longer on the table. U.S. President Donald Trump is now calling Washington’s commitments into question at the same time that it is pushing regional allies to confront China more forcefully.

The more that the United States overlooks Southeast Asian viewpoints and preferences, the more that it will see its influence and relevance in the Indo-Pacific wane as China’s waxes. Protecting U.S. interests is vital, but making demands without offering more in return is counterproductive.

Nowhere is this divergence clearer than in how the U.S. defense secretary described the growing threat from China. Hegseth argued that “China seeks to become a hegemonic power in Asia” and urged regional allies and partners to do their part to deter Beijing. He called attention to China’s harassment of neighbors in their own waters and insisted that an invasion of Taiwan “could be imminent.”

Emphasizing that the United States sees China as a threat can be useful. Asian allies and partners have been bracing for a worst-case scenario, particularly after seeing Trump’s disdainful treatment of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in February. The abruptness with which Trump turned his back on Ukraine and sided with President Vladimir Putin’s Russia prompted fears across Asia that the administration would cut a deal with China at the expense of smaller, vulnerable states in the region.

Indeed, some aspects of Hegseth’s message reinforced these exact fears. Burden-sharing was a consistent through line in the speech and the administration’s policy thus far, both in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Hegseth’s exhortations that Indo-Pacific allies raise military spending to 5 percent of their GDPs fell on deaf ears. These are politically difficult asks, which could also create the pretext to abandon these allies if they fail to meet expectations.

This rhetoric also contains clear echoes of President Richard Nixon’s Guam doctrine, which heralded a three-decade period of U.S. withdrawal from Southeast Asia. When the United States pulled back from the region in the 1970s, it also fueled regional fears of unchallenged Chinese dominance.

In this spirit, Hegseth’s consistent references to “communist China” proved to be both reassuring and alarming. Hegseth seemed to be signaling a new cold war mindset that would mean real resources deployed to counter Chinese aggression. But this mindset might also mean more pressure against allies who stand accused of hedging.

Or it might not mean much at all. Cold War rhetoric cropped up in the first Trump administration, especially among more traditional Republican Party hawks. But these figures are now on the outs, and there are there are clear ideological divides within the current administration over how to deal with China. Trump may hope to make a grand deal with Beijing and see this language as a way to ratchet up pressure prior to trade negotiations. And, despite the venue, this rhetoric may also simply be intended to appeal to a domestic audience in the United States.

Regardless, Washington’s regional allies remain wary of escalation. However upset they are over its aggression, most countries in the region remain economically dependent on China. Given the tremendous power imbalance and economic exposure, no one in Southeast Asia or the Indo-Pacific wants war. Even the Philippines, whose defense secretary echoed Hegseth’s warnings about China at Shangri-la, has not necessarily abandoned hedging.

As such, Manichaean language raises concerns that the Trump administration may engage in brinkmanship that demolishes the economic foundations of the region’s development. Trump’s trade war with China and the global tariffs that he has threatened—some of the harshest of which fell on Southeast Asia—only enhance this fear.

Despite the Cold War language, a number of concrete moves in Washington have also driven fears of abandonment. Initially, the appointment of figures such as Mike Waltz and Alex Wong to the National Security Council offered reassuring evidence of the administration’s Indo-Pacific focus. But their sudden departures in recent months, along with the dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development, the wider National Security Council, and other elements of U.S. policymaking all call into question the administration’s commitments to global leadership. As some have argued, this White House could well adopt a “spheres of influence” approach and retrench to the second island chain, leaving Southeast Asia and the rest of the Indo-Pacific alone to face China.

Trump officials, including Hegseth, continue to refer to the Indo-Pacific as Washington’s “priority theater.” Yet it is clear that the administration’s attention is elsewhere, with Trump recently calling Putin to discuss Ukraine and traveling to the Middle East to promote his family’s business interests. And in March, the Pentagon extended the deployment of one aircraft carrier in the Red Sea and ordered a second carrier group there to combat Houthis in Yemen. These moves suggest a distracted United States that is incapable of fulfilling its commitments to Asia.

The administration will have a chance to bolster regional confidence if it shows up to summits such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and East Asia Summit this fall. During his first term, Trump skipped the annual ASEAN Summit three years in a row, opting to send less senior representatives in his place. These absences are missed opportunities to demonstrate U.S. staying power in a region that places a premium on showing up.

But showing up will only go so far. As long as this administration’s rhetoric and actions remain mismatched, the United States will see its influence slowly erode. If Washington cannot reassure allies that its commitments are ironclad, then they will not take risky steps to confront China that could leave them out in the cold.

Hegseth’s speech, both because of its own inconsistencies and its divergence from U.S. actions, was not enough to shore up U.S. influence.

X: @hmarston4

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.