How smuggled US fuel funds Mexico’s cartels

Every evening at dusk, about 90 kilometres north of Mexico City, the main highway lights up with flashing strobes. Truck drivers know this means one thing: illicit fuel is sold here.

For decades, criminal groups in Mexico have stolen fuel from the state, a practice known as huachicol. But in recent years this has been eclipsed by a new and advanced form of smuggling — diesel and gasoline moved across the border from the US via truck, train or sea.

“What we’re seeing is a major shift in the illicit fuel game that organised criminal groups in Mexico and co-conspirators in the United States in some cases are playing,” says David Soud, head of research and analysis at international security consulting firm IR Consilium. “What this showcases is how smart and how adaptive these organisations are in their business models.”

Estimates from the last five years suggest that illegal diesel and gasoline make up anywhere between 16 and 27 per cent of Mexico’s annual fuel consumption — between 172,000 and 290,000 barrels per day. That could have a final retail sale value of between $12bn and $21bn a year.

“It’s a very big black market,” says Samuel León, a Mexican researcher who has written a book on fuel theft. “It’s one of the biggest black markets for hydrocarbons on the planet.”

Vast organised crime networks, some connected to major drug cartels such as Jalisco New Generation Cartel, known as CJNG, are exploiting Mexican import policies and using bribes, coercion and violence to smuggle fuel from the US and flood the market with discounted diesel and gasoline. The illicit trade is now playing a key role in financing these groups, with stolen fuel becoming the most significant non-drug revenue source for Mexican cartels, according to the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

“The operating costs of drug trafficking are financed with peripheral activities . . . extortion, kidnapping, robbery, fuel theft,” David Saucedo, a Mexican security expert, says of the cartels, who oversee a parallel economy that encompasses everything from selling avocados to providing WiFi.

Under pressure from the Trump administration, Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum is trying to crack down on illegal fuel imports. But the cartels’ connections to the authorities, as well as the huge sums to be made, mean that they have the protection and incentive to continue.

From pipeline tapping to border smuggling

There are about 22,000 “irregular self-consumption points” across Mexico, according to estimates by the Mexican Association of Service Station Providers — 1.6 illegal outlets for every regulated petrol station.

Drivers use these makeshift petrol stops to fill up at a discount, though in doing so they also risk damaging their vehicles with diluted fuel. In some areas, the practice is so prevalent it is captured in Google Street View images.

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) { #roadside-roadside1-loading { aspect-ratio: 2.176; } }

@media screen and (min-width: 980px) { #roadside-roadside1-loading { aspect-ratio: 2.227; } }

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) { #roadside-roadside2-loading { aspect-ratio: 2.176; } }

@media screen and (min-width: 980px) { #roadside-roadside2-loading { aspect-ratio: 2.227; } }

The small roadside operations selling huachicol with impunity reflect decades-long practices of siphoning fuel from trucks or stealing it from Pemex, the indebted state-owned petroleum corporation, either from its refineries or by directly tapping pipelines. Pemex had around 17,000 barrels stolen per day last year, according to the company’s annual report, generating 20.5bn pesos ($1.1bn) in losses.

Daniel Enrique Guerrero, a former energy ministry official, says theft from Pemex has long been a problem in the country. “There is a very Mexican custom to think that if you steal from the government you aren’t stealing from anybody.”

The illicit fuel market is biggest in states close to the US border and central areas of Mexico, where Pemex’s pipelines transport fuel to regional terminals. In Nuevo León and Zacatecas, contraband fuel accounted for more than 40 per cent of consumption in 2025, according to estimates by FuelPricing, a Mexican analytics company.

Illicit fuel consumption is highest in northern and central states

Share of the illegal fuel market by state, 2025

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) { #illicit-market-map-loading { aspect-ratio: 1.053; } }

@media screen and (min-width: 750px) { #illicit-market-map-loading { aspect-ratio: 1.047; } }

Interviews with more than a dozen analysts, industry experts and government officials, as well as trade data and satellite images, show transnational smuggling now makes up the bulk of Mexico’s black market fuel. Many interviewees declined to speak on the record for fear of reprisals.

Most of these illegal imports are transported from the US, in particular Texas. This is usually achieved with the aid of corrupt officials and falsified documents, industry participants say. But a Mexican tax policy is also believed to have inadvertently incentivised the rise in smuggling.

The Mexico tax authority has not released an estimate of fuel smuggling since the end of 2022. But analysts believe the vast size of the market means much of it must be transported by sea. A typical tanker truck can carry about 190 barrels, versus some 250,000 barrels on vessels like the Challenge Procyon.

“The volume is so high, so big that it’s very hard to cross over the land border,” says industry analyst and consultant Eduardo Chagoyán, who worked at Pemex for 30 years and now runs FuelPricing. “Some must be coming in by rail, and without a doubt the rest by tanker.”

An FT analysis of tanker shipments from the US sheds light on how this process works.

According to the Mexican tax authority, industrial lubricants used to protect machinery, which are not subject to the IEPS tax, are often used as a cover story for smuggling fuel. The agency noted in 2022 that imports vastly exceeded national demand. Since then, the surge in deliveries of lubricant-related products has continued, according to data from Trade Data Monitor.

Port records for the Cosmic Glory, which arrived in Mexico’s Tampico port in February, list it as transporting “additives for lubricant oils”. But data from trade analytics platform Kpler based on the US bill of lading states that the vessel was loaded with diesel. The ship’s owner, China’s Bank of Communications, did not respond to a request for comment.

@media screen and (min-width: 740px) { #buques-cg-loading { aspect-ratio: 2.121; } }

A comparison of Mexican records for Altamira and Tampico ports with data from the corresponding US bills of lading reveals a further 11 instances of ships recorded as transporting chemical additives for lubricants or paraffin oils carrying diesel.

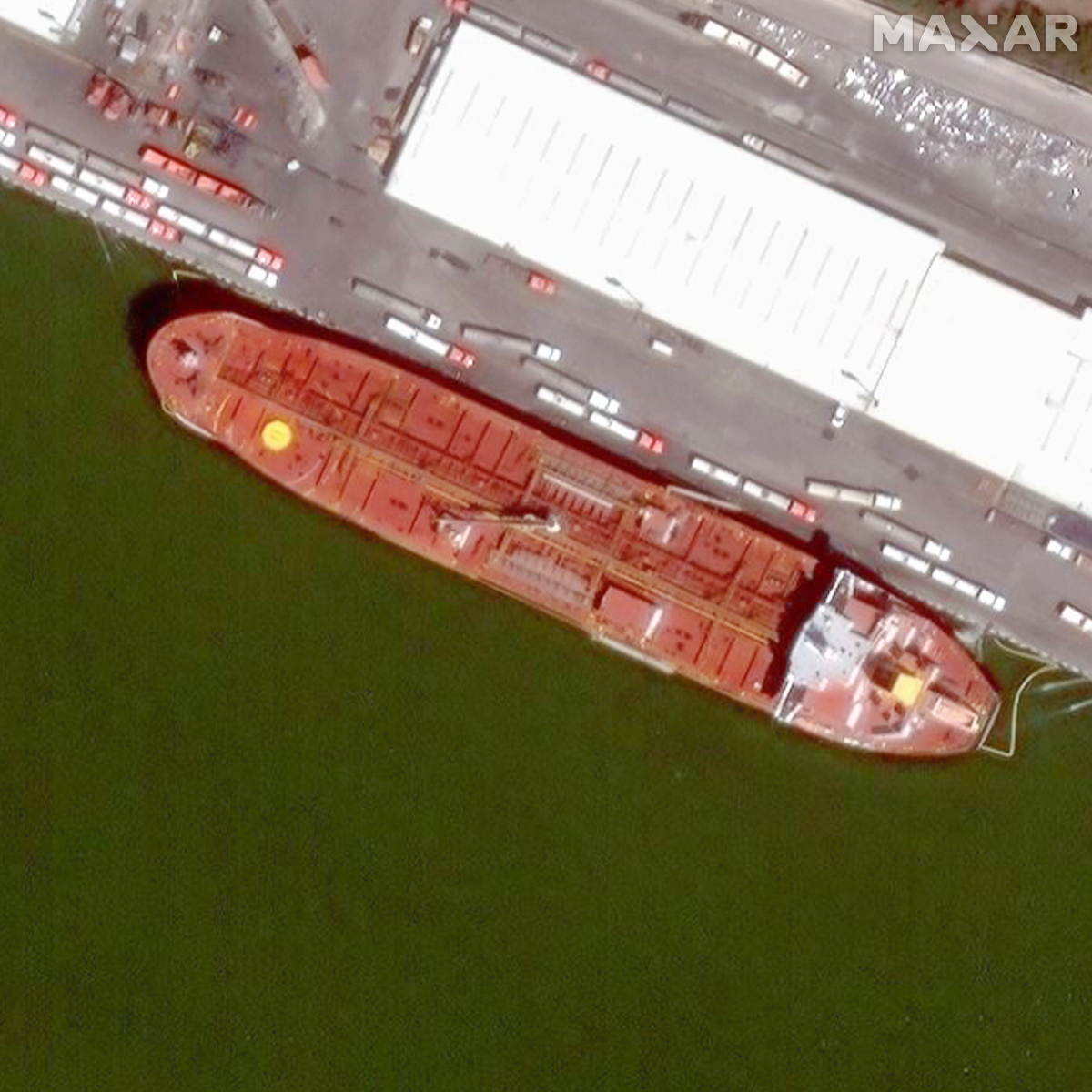

In all of those cases, the ships docked at cargo bays without the usual infrastructure needed to unload, measure and store fuel. Satellite imagery and drone photography shows they were met by lines of tanker trucks, which were filled by hosepipes running from the ships. The unloading process often spanned several days, as the tankers can fill more than 1,000 trucks.

Since 2023, ship tracking data and satellite imagery show 42 incidents of ship-to-truck transfers by 28 different vessels at Altamira and Tampico, suggesting that the problem extends beyond the dozen mismatched customs records the FT was able to obtain. In 20 cases, tankers docked at a facility owned by US engineering and construction company McDermott.

The transfers at Altamira ceased after being reported by Mexican news outlet Código Magenta in March 2024. The next month, the publication reported on another incident in neighbouring Tampico port. A lull followed, but since November at least 17 ship-to-truck transfers have taken place in Tampico.

The last resulted in the Challenge Procyon’s seizure. Tampico port records state that the tanker was carrying “additives for lubricant oils”, but the US bill of lading shows it was transporting ultra low sulphur diesel.

@media screen and (min-width: 740px) { #buques-cp-loading { aspect-ratio: 1.964; } }

The ship’s owners, Kyoei Tanker Singapore, confirmed to the FT that the Challenge Procyon was loaded with diesel and said that they had entered into a contract with another large tanker company for the use of the vessel.

They added that “the location and method of receiving and storing the cargo were entirely at the choice, direction and discretion of the cargo receiver”, and that Kyoei Tanker Singapore “strictly abides by all laws related to its role as a vessel owner”.

Although ship-to-truck transfers of hydrocarbons are not illegal under Mexican law, they require a special permit and experts say it is highly unusual in ports with developed infrastructure, such as the fuel terminals in Tampico port.

“It’s one thing if you’re seeing direct offloading into tanker trucks because there is some kind of issue with the regular storage facilities and the regular infrastructure,” Soud of IR Consilium says. “It’s another thing entirely when you see this happening where oil or fuel customarily is not unloaded at all. That immediately suggests that what you’re looking at is a clandestine, streamlined delivery system for smuggled fuel.”

International Seaways, which owns four vessels that conducted ship-to-truck transfers at Altamira, told the FT that “this process is fully in line with standard industry practices” and that “the vessels are routinely attended by authorities and port agents”. It added: “Before any international voyage, the company always ensures the vessels are in compliance with all regulations, including the necessary documentation and permits.” McDermott, owner of the facility in Altamira, declined to comment.

Since 2022, Mexico’s customs have been controlled by the military as part of a vast expansion of its power under former Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador. He argued it would cut corruption, but in that time illegal imports have exploded in volume. Mexico’s Navy told the FT that “any illegal situation is not tolerated”.

Francisco Barnes, a former energy regulator, says it is “unfathomable” that fuel smuggling could happen at this scale without the authorities realising. “Either they’ve been totally blind and incompetent or complicit.”

Huachicoleros

Criminals engaged in Mexico’s illicit fuel industry have their own name: “huachicoleros”. They have accordion ballads written about them by bands glorifying narco culture and their own patron saint, “El Santo Niño Huachicol”, a Christ-like child holding a siphon and a jerrycan.

The violence, corruption and environmental damage that accompanies the practice is devastating. Over the past two decades, Mexican cartels have pushed homicides and missing people numbers to record highs and deepened their grip on territory in the country, which the World Bank’s Organised Crime Index ranks third in the world for criminality.

In 2019, a suspected pipeline tap in Tlahuelilpan, a town in Hidalgo, sprung a leak and locals crowded around the fountain of petrol to fill containers. The fumes ignited and the resulting explosion killed at least 137 people.

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 video.

The dark heart of Mexico’s illegal fuel industry today is Tamaulipas state, which borders Texas. US authorities warn that cities such as Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa and Matamoros and the highways surrounding them are run by organised crime groups that operate with impunity.

The Gulf Cartel, which is active in the border cities of Matamoros and Reynosa, reportedly demands a payment of $500 per truck to allow legally imported petrol through Matamoros, which is just across the border from Brownsville, Texas. In late 2023, suspected cartel gunmen forced a dozen US fuel trucks to dump their cargo after crossing into Mexico.

An April report by the US Drug Enforcement Administration states that CJNG has formed an alliance with a faction of the Gulf Cartel to smuggle drugs to the US. The report claims the partnership gives CJNG access to Altamira port, which is used to import precursor chemicals needed to manufacture narcotics.

Cartel connections to illegal fuel imports can be traced through a transportation company allegedly involved in smuggling petrol. Mefra Fletes has 600 trucks and operates throughout Mexico but has no website and little digital footprint.

A former director is the brother of the mayor of Teuchitlán, who was arrested by Mexican authorities last month in connection to the CJNG cartel. Mexico’s attorney-general said the mayor and his two brothers owned all the trucks found during two recent fuel raids.

Mefra Fletes vehicles are clearly visible in photos of one of the raids, in Ensenada. The company’s trucks also appear in social media images of a ship-to-truck transfer in Guaymas. The FT was unable to contact Mefra Fletes for comment.

As with many parts of Mexico’s criminal underworld, cross-border fuel smuggling can only function with the involvement of people working for the country’s authorities.

Shipping records state that the fuel importer for at least five of the ship-to-truck shipments into Tampico, including the Challenge Procyon, was a company called Intanza. A recent investigation by non-profit Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity documents business ties between owners of the company and Francisco Martínez, the finance director of Tampico port responsible for collecting taxes on imports.

A declaration of Martínez’s assets obtained by the group shows he reported an income of more than 500,000 pesos (about $30,000) a month — nearly 10 times his salary from the port. Martínez was dismissed, along with another port official, four days after the investigation was published. He could not be reached for comment.

In late March, the Mexican tax authority revoked Intanza’s import licence, as well as that of Azteca Cone, another importer for several of the tanker visits to the cargo bay in Tampico. The two importers could not be reached for comment. On May 20, the Port Authority of Tampico dismissed its general director in a statement without explanation.

“It is extremely unlikely that this level of illicit business could be conducted without collusion from people on the inside,” Soud says. “That collusion could be voluntary. It could also be coerced. Certainly authorities in Mexico and certainly private sector actors who should know better in the United States are in the mix.”

Illicit fuel, licensed pumps

The price of fuel is ingrained in Mexican politics. Former president Lopez Obrador’s signature innovation was the morning news conference, the mañanera, which helped him entrench his political narrative.

Fuel had such importance that each Monday, the conference opened with a section called “who’s who in prices”. The consumer protection agency Profeco would highlight the lowest priced gas stations, while reprimanding the highest. Profeco now goes around the country posting banners warning drivers not to fill up at a station that is “going overboard with prices”.

The press conferences have continued under Sheinbaum, and in February her government announced a voluntary 24 peso ($1.3) per litre cap on gasoline pump prices.

According to an April survey by PetroIntelligence, a Mexican gasoline and transportation analytics company, three out of four petrol station owners in the country believe that fuel smuggling, theft and tampering are on the rise.

In 2024, Mexico’s largest convenience store chain, Oxxo, temporarily shut all its stores in Nuevo Laredo, in part because of threats that culminated in employees being held hostage. The criminals wanted to force the Monterrey-based company to buy fuel from specific suppliers, an executive said at the time. Oxxo only reopened after it was promised more security from local authorities.

Just weeks later, local chamber of commerce representative Julio César Almanza, who had spoken out about criminal groups battling for control of the local customs office, was murdered in Matamoros. That was a year after José Luis Palos, president of the Nuevo Laredo Gas Station Association, was killed after reporting threats from criminals to force them to buy tanks of clandestinely imported gasoline.

“The plata o plomo [threat of money or bullets] is real, they come to you and say . . . ‘You buy this from me or we kill you,’” says researcher León.

National data suggests some petrol stations could be selling contraband fuel. Beginning in 2023, service station sales of gasoline began to exceed their supply from legitimate sources.

It means the Mexican government should be putting special attention on low prices rather than high ones, according to Pedro Roldán, a consultant for PetroIntelligence.

A legal representative for Jalisco-based KPetrom told the FT that the two Nuevo León stations “were not part of the group” and had used the company’s branding without permission. The owners of the two stations could not be reached for comment.

A cross-border response

Fuel smuggling is now squarely in the sights of US authorities, which have issued multiple sanctions against individuals and businesses, while prosecutors are pursuing criminal cases related to the illegal oil trade.

“Fuel theft and crude oil smuggling are cash cows for CJNG’s narco-terrorist enterprise, providing a lucrative revenue stream for the group and enabling it to wreak havoc in Mexico and the United States,” said US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent in early May.

Since September, the US has imposed sanctions on dozens of Mexican nationals and businesses suspected of being linked to fuel theft networks that generate tens of millions of dollars for the CJNG. The investigations also revealed some of this fuel is now being sent to the US.

One of the CJNG members, Iván Cazarín Molina — known as “El Tanque”, meaning “the storage tank” — operates a fuel storage facility in Veracruz. The US Treasury asserts that Molina sells stolen fuel in ostensibly legitimate petrol stations and is also involved in smuggling it into the US.

This “reverse huachicol” has been exposed in another US case. In April, a Utah-based couple were arrested for allegedly selling fuel stolen from Pemex that had been transported north.

The US response comes as Donald Trump piles pressure on Sheinbaum to crack down on drug cartels and fuel smuggling if she wants to avoid tariffs and US military intervention.

As well as arrests and seizures, Mexico’s president is implementing reforms to improve the traceability of crossings from the US. At the northern border in April, long lines of trucks formed at major international crossing points as the authorities stepped up inspections of vehicles importing hydrocarbons. But the security issues facing Sheinbaum’s government, from disappearances to violent crime, mean rooting out the problem is not easy.

“The Mexican state has been overwhelmed for a long time,” says Eduardo Guerrero, a security analyst at consultancy Lantia Intelligence. “A scenario is coming together where we’ll have a big confrontation between the Mexican state and the Jalisco Cartel, where I think US collaboration will be indispensable.”

The US state department told the FT they were committed to working with Mexico to disrupt fuel theft networks and urged US companies to “do their due diligence” when selecting trade partners.

León says the authorities have to reduce the violence rather than “the fantasy” of taking out the entire fuel smuggling industry. He adds that as long as the tax differences at the border remain, someone will try to profit. “These groups aren’t going to disappear . . . they are corporations that kill.”

How far Sheinbaum is willing to go to eliminate the practice is unclear — especially given the violence that accompanies any challenge to the cartels’ power. Her security minister, Omar García Harfuch, was the victim of a daylight assassination attempt by the CJNG in Mexico City in 2020.

“It takes enormous political will,” Soud says. “You’re taking on organisations that have significant capabilities to strike back if you push them hard enough.”

Additional reporting by David Sheppard

Video and photos of vessel seizure and raids used in the opening of this piece from the Mexican government. US export data from Kpler and ExportGenius. Mexico import and customs data from C4ADS and CargoFax. Vessel tracks from Kpler and Global Fishing Watch. Data for the IEPS rate for regular petrol, the US Gulf Coast gasoline regular spot price, and average pump prices for regular petrol from PetroIntelligence. Nuevo León pump and wholesale terminal prices from PetroIntelligence and FuelPricing. Wholesale fuel prices in the north-east of Mexico based on maximum discounts possible at Pemex terminals across the region.