Another Bad Night in Kyiv

Another Bad Night in Kyiv

A tired public is enduring a wave of Putin’s attacks on civilians.

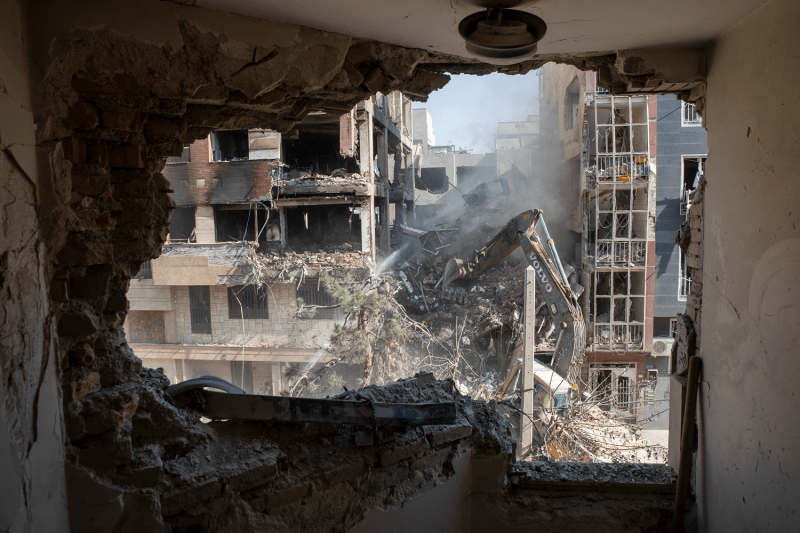

A building is surrounded by rubble following Russian drone strikes in Kyiv on June 10. Tetiana Dzhafarova/AFP via Getty Images

It was just after midnight on June 10, and Kyiv’s curfew had just begun when news of incoming rockets and drones buzzed on our phone screens. I was sitting on a balcony, smoking, when I saw what looked like a huge star dissolve in the sky. To my surprise, I managed to put out my cigarette in an ashtray before I went inside, where I was then stuck with a difficult choice: move to the corridor protected by two walls or stay in my apartment. Me and my friend, Iryna, gave it some time. After a long day, leaving your bed is a difficult decision—even when rockets are flying. Then came a series of bangs, making the decision for us.

“As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me,” novelist George Orwell wrote during the London Blitz. Nights in Kyiv feel the same, except here it’s a remote-controlled drone doing the killing. Cheap drones keep hitting the city one after the other, rolling endlessly off factory lines to hit civilians in Kyiv. But that night was unusually bad.

It was just after midnight on June 10, and Kyiv’s curfew had just begun when news of incoming rockets and drones buzzed on our phone screens. I was sitting on a balcony, smoking, when I saw what looked like a huge star dissolve in the sky. To my surprise, I managed to put out my cigarette in an ashtray before I went inside, where I was then stuck with a difficult choice: move to the corridor protected by two walls or stay in my apartment. Me and my friend, Iryna, gave it some time. After a long day, leaving your bed is a difficult decision—even when rockets are flying. Then came a series of bangs, making the decision for us.

“As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me,” novelist George Orwell wrote during the London Blitz. Nights in Kyiv feel the same, except here it’s a remote-controlled drone doing the killing. Cheap drones keep hitting the city one after the other, rolling endlessly off factory lines to hit civilians in Kyiv. But that night was unusually bad.

I was staying in a Soviet apartment block in Solomianskyi, a district in Kyiv. As the explosions rocked our apartment building, a neighbor in her 70s ran out to the corridor in her nightgown, crying and struggling to gather her emotions. For a moment, I was worried she might have a heart attack. This was one of the largest attacks of the war so far, Russia’s response to Ukraine’s Operation Spider’s Web, which successfully destroyed Russian aircraft with concealed drones. Attacks on Kyiv are constant, but this was on a different scale.

Messages from friends flooded my phone, some of whom were veterans of drone strikes themselves. Terror creates an incredible sense of solidarity, prompting reassurances, sarcastic jokes, and swearing. “How is the Kyivian night for you?” said a fellow journalist, Kristina, who then kept a running count of drones for me.

An explosion came every few minutes. Ukrainians have dubbed the Iran-developed Shahed drones “mopeds,” thanks to their sound. They sound like mosquitoes buzzing near your ears, which doesn’t make for easy rest at 3 a.m. It’s a menacing whine that gets closer and closer before the blast. The car alarms outside were going crazy.

The fifth-floor corridor we moved to smelled like valerian extract—an old-school stress reliever that was popular in the Soviet Union. The two older ladies in their nightwear pulled up a chair for me. “You shouldn’t sit on the floor, gotta bear children,” one said. They were former engineers and had been given apartments in the building back in the Soviet days. The two had the best time that night, turning our impromptu bunker into a local salon. They told stories of the first days of the war, surviving on pieces of bread, recalling the imminent danger of incoming Russian tanks, troops, and torture. I learned a great deal about the late husband, a Georgian like me, of one of the women.

Our chat was only interrupted by the sounds of the shelling. People who live through this daily need to narrate their stories. It makes their suffering and everyday courage matter, and it reassures them that their bravery is not in vain. Halfway through, they asked about the fight between U.S. President Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

At first, adrenaline flooded my brain, making everything around me sharp and clear. After hours of this, boredom started to take over. I refreshed Telegram and X, my fate in the hands of already tired soldiers on air defense. I felt helpless and brave at the same time, proud of myself for not breaking down.

The shelling got louder and more intense, and we moved to the building’s first floor. An intense debate ensued on whether to use the elevator or the stairs At one point, I thought: How have we built weapons that cover the globe in 10 minutes, but it still takes eight hours to fly across the Atlantic?

The nearest shelter was a 10-minute walk—not a relaxing stroll when drones are flying. On the ground floor, kids and dogs sat alongside each other, shaking with every blast. In between bombardments, there was near-total silence. I looked at a 9-year-old boy in the corner and thought of the terrifying normalization of war. He seemed much better at handling this than I was.

By now, he probably knows more about missile types than most NATO defense ministers. Ukrainian Telegram channels have gotten very good at describing what flies your way, how many Russian destroyers took off carrying what kind of missiles—such as cruise, ballistic, hypersonic ones like the Kinzhal, and the like. It lets one decide the costs and benefits of going to a shelter.

This sense of endless terror is exactly what Russia wants Ukrainians to experience. It wants people to think that it can keep going indefinitely, that it can bear the cost of continuous war. The message is not just for Ukraine, but also for people in the United States and in Europe: Moscow aims to exhaust, frighten, and wear down support for Ukraine’s survival, defense, and cause.

The Kremlin wants to pass terror off as a legitimate act of war, calling it retaliation for Ukraine’s latest success in destroying reportedly 30 percent of Russia’s strategic bombers, and casts civilian casualties as collateral damage. But one must ask: What did the British visa center have to do with the war? What was hidden in Odessa’s maternity hospital? This is simply Russia’s way of war: total destruction and disregard for civilian life.

Between the bombs, I remembered a video of a Georgian man in the Abkhazia war of 1992-1993, where Russia backed separatist forces. The man was throwing soil with his bare hands over his son’s dead body and saying, “Who can forgive this? No generation can ever forgive this.” Georgians haven’t forgiven Russia, and Ukrainians won’t either.

The next morning, Kyiv carried on as if nothing had happened. People in the street looked fresh and alive, even if they barely slept. But beneath that quiet strength is the weight of another night spent under fire and scars of more than three years of war.

For Ukrainians, there is no other choice but to continue. As I sat next to the older ladies, Soviet in their outlooks, I thought: This is what Russia has done. It woke something up in these people, even those of Soviet education. A kind of pride, courage, and resilience that even a bad peace deal won’t shake. If three years of bombs haven’t broken people here, nothing will.

Yet Russia’s goal of exhausting the West may be working. The blasts, the bodies, and the blackouts blur into the background. This war remains someone else’s tragedy. It’s far away. That is what makes this war worse than the one Orwell lived through—the fact that the West still allows it. Washington permits it. And it’s not for lack of means back lack of will. The terror Russia unleashes is expected, but what’s harder to accept is the silence of those who claim to stand for something better.

Ukraine isn’t asking anyone to die for it. Ukrainians are doing the dying. What it’s asking for is support from countries that say they care about civilization, about liberty, and about truth.

That morning, a blood red sun broke through the heavy black smoke of burnt-out apartments, with the phone alert app, e-Triyvoha, clearing us to go to sleep. My friend went to work, having slept all of three hours. I stayed behind. Soon, another air raid came. I couldn’t take it anymore and walked into the shower.

Ani Chkhikvadze is a Georgian reporter based in Washington.

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.