An Iran oil shock would put global growth on a slippery slope

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Lower energy prices have been a rare bright spot for US consumers dealing with heightened inflation. After Israel’s strike on Iranian targets, that may well reverse.

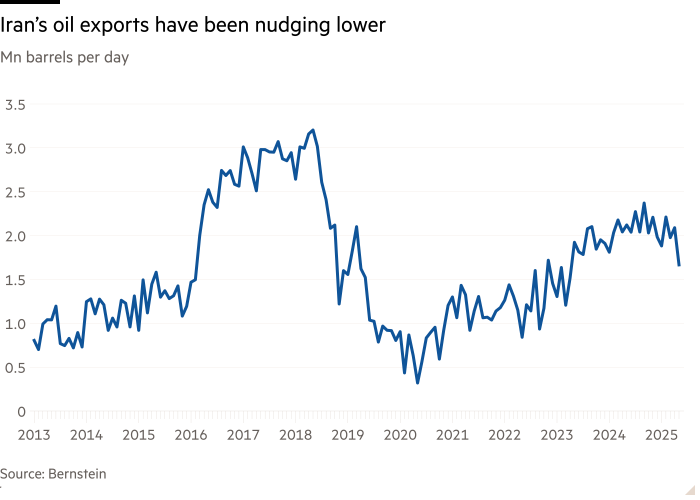

The Iran shock presents two risks to the price of oil, which rose 8 per cent to $74 a barrel on Friday morning, a sizeable jump for a single day. The first is that, in the context of the rising hostilities, Iran’s current crude exports, which have already been softening, could fall further.

That, in itself, would not be insurmountable. Iranian oil exports amounted to 1.7mn barrels a day in May according to Bernstein, a broker, less than 2 per cent of global consumption. More meaningfully, Opec — of which Iran is a founding member — has already announced a series of monthly production increases totalling almost 960,000 barrels a day to the end of June. Analysts expect that Opec will gradually release a total of 2.2mn barrels a day back into the market by reversing previous cuts.

These are rough numbers, and timing matters. But seen in this light, a reduction of Iranian exports would merely rebalance an oversupplied market. A reasonable assumption might then be that oil could return to somewhere between the $75 a barrel at which it started 2025 and its $80 a barrel average for 2024, dependent on how long the disruption lasts.

The second and much bigger risk to oil supply would be disruption to tanker traffic through the Strait of Hormuz. A fifth of global oil consumption flows through this narrow waterway flanked by Iran, as well as Qatari exports of liquefied natural gas. That would be an entirely different kettle of fish, though its impact is hard to assess. JPMorgan analysts, for reference, estimate that in a severe outcome, oil prices could surge as high as $130 a barrel.

That would spell trouble for consumers — American ones, in particular. Falling petrol prices have helped keep a lid on US inflation, which rose 2.4 per cent in the 12 months to the end of May. Should oil reach $120 a barrel, that alone would add 1.7 percentage points to consumer price inflation, JPMorgan estimates.

These are what ifs, for now. Iran has never closed off the Strait of Hormuz, despite repeated threats. It would be practically hard to do so. Israel has good reason to spare the country’s oil infrastructure, given US President Donald Trump’s interest in low oil prices. In early US trading on Friday, stocks of oil producers such as ExxonMobil rose, but consumer-related companies such as retailer Target and coffee chain Starbucks were down only slightly.

But more uncertainty will surely creep into prices and forecasts. Oil powers the global economy, and higher inflation makes it hard for central banks to cut interest rates. Growth expectations have already been thwacked. If this new conflict drives oil prices higher, it would hit them even harder.