The Novels We’re Reading in March

Books

The Novels We’re Reading in March

From a killing in the West Bank to horror in a postapocalyptic convent.

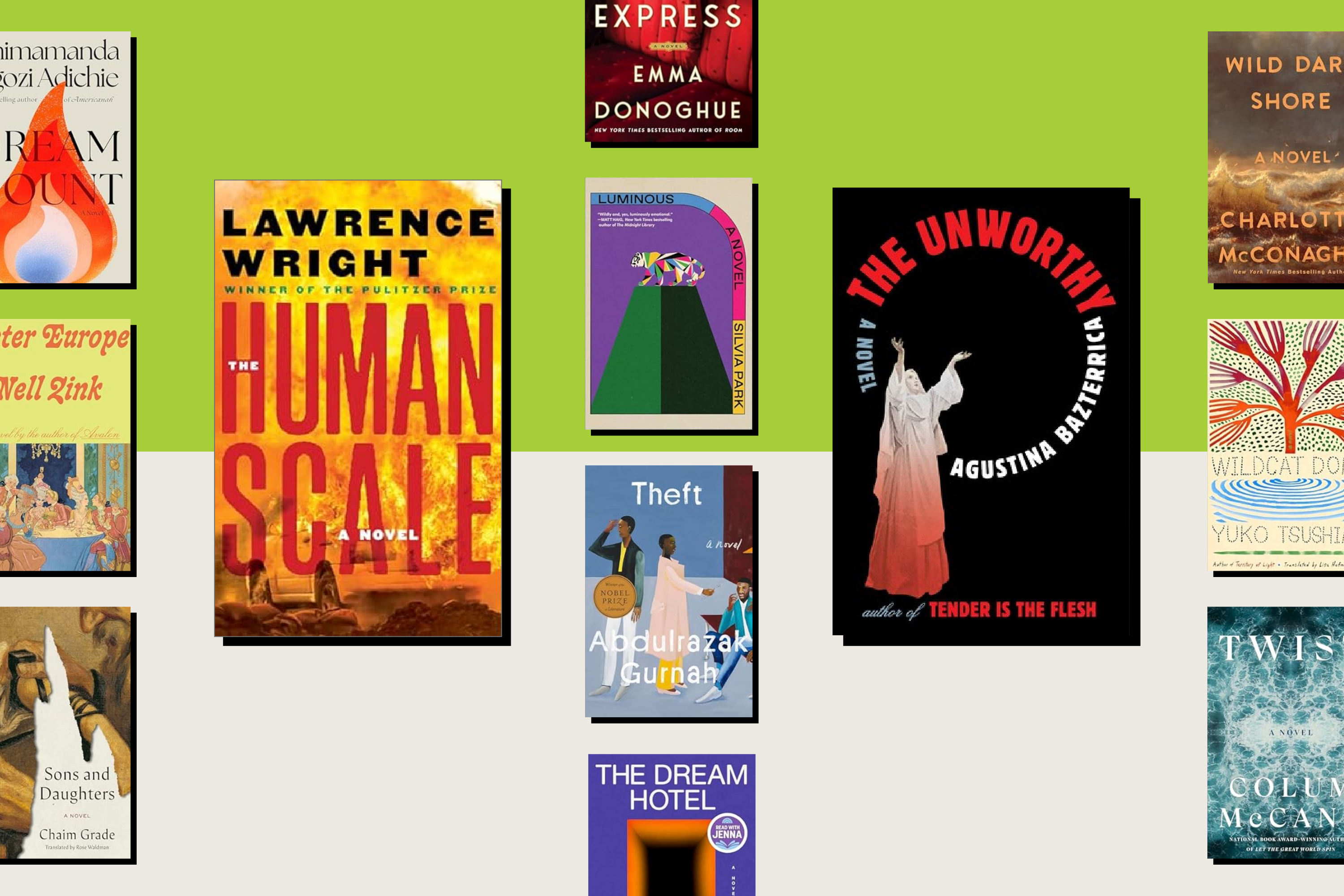

Publisher cover images

This month, we’re reading about dystopias real and imagined, from a crime drama set in the Israeli-occupied West Bank to a novel about a convent in a climate-ravaged world.

The Human Scale

Lawrence Wright (Knopf, 448 pp., $30, March 2025)

This month, we’re reading about dystopias real and imagined, from a crime drama set in the Israeli-occupied West Bank to a novel about a convent in a climate-ravaged world.

The Human Scale

Lawrence Wright (Knopf, 448 pp., $30, March 2025)

New Yorker staff writer Lawrence Wright is no stranger to political storytelling. The author of more than a dozen books, Wright won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for The Looming Tower, which is widely regarded as the definitive account of events leading up to the 9/11 attacks. Wright’s latest work, The Human Scale, is a rare foray into fiction.

The Human Scale begins in Jordan in 2022, when Palestinian American FBI agent Anthony Malik barely survives the detonation of a Hamas bomb discovered at Amman’s Queen Alia International Airport. Months later, he returns home to New York City traumatized and adrift. With Malik’s future at the FBI uncertain, he travels to the occupied West Bank in September 2023 to attend his cousin’s wedding in Hebron.

Malik’s father immigrated to the United States from Hebron, but Malik had never visited the city. When he arrives, he finds that Hebron is “basically a military cantonment ruled by the Israel Defense Forces,” where “death exerted a magnetism.” Malik’s grandfather’s olive groves are under attack by radical Jewish settlers from nearby Kiryat Arba, an illegal settlement “renowned for its fanaticism.”

Those settlers are protected by complacent Israeli police officers, with whom Malik becomes entangled after their chief is assassinated. Malik forms a testy alliance with officer Yossi Ben-Gal as the two attempt to uncover who is behind the killing. The novel is as much a tale of their rocky relationship as it is a panorama of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

As the story elapses, Malik—who downplayed his Muslim and Palestinian identities in the United States after 9/11—comes to terms with the fact that in Israel and Palestine, “he would always be under suspicion,” despite his U.S. citizenship. As Yossi tells Malik, “Whatever you are in America, here you are an Arab.”

Yossi, meanwhile, is vehemently anti-Palestinian, but he harbors qualms about the violent Kahanist ideology spreading in Kiryat Arba. The Israeli officer agrees to collaborate with Malik because he is mistrustful of his coworkers and their ties to settlers.

Though Malik and Yossi represent two poles, they are complemented by characters who embody a spectrum of perspectives in the conflict. Among them are Malik’s cousin Dina, who broke off an engagement to a Hamas bombmaker for peacenik Jamal (inspired by real-life nonviolent activist Issa Amro). Sara, Yossi’s daughter, is a left-wing academic who feels herself “becoming less Israeli” because the country’s politics are “impossible to defend.”

“The Human Scale” is the title of a paper that Sara wrote, a project on the disproportionate prisoner exchanges between Israel and Hamas. Sara cites the bargain that led Hamas to free Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier the group abducted in 2006: 1,027 Palestinians for one Israeli soldier. The book is set in the run-up to Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel, and the imbalance between Palestinian and Israeli deaths in the ensuing Gaza war looms large.

Wright’s choice of title is a testament to his nuanced understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Although he humanizes all Israelis and Palestinians, his focus on the banality of Palestinian dispossession renders the book free of the false balance (or bothsidesism) that seeks to equate Israeli violence with resistance from a population that lacks political rights.

The Human Scale is part crime novel and part political manifesto. Ending on Oct. 8, 2023, the book is a haunting plea for justice that includes Wright’s explicit call for Israel to end its occupation of Palestine. The story is spellbinding, but it hews so close to reality that it may leave readers with a bitter aftertaste. As one of Malik’s relatives tells him upon his arrival in Hebron, “Nothing ever changes in our lives except by violence.”—Allison Meakem

The Unworthy: A Novel

Agustina Bazterrica, trans. Sarah Moses (Scribner, 192 pp., $28.99, March 2025)

It is perhaps no surprise that Agustina Bazterrica—one of Argentina’s buzziest writers, whose 2017 international bestseller Tender Is the Flesh imagined a world where cannibalism is legalized—has returned with another grotesque and searing work.

The Unworthy, published in Spanish in 2023 and newly translated into English by Sarah Moses, is Bazterrica’s take on the post-apocalyptic dystopia. It’s a fever dream of a novel set in a religious order called the House of the Sacred Sisterhood, which worships a god, but not the “erroneous God, the false son, the negative mother.”

Like many recent dystopias, Bazterrica’s world is ravaged by climate catastrophe. The Earth has been torn apart by “wars that coincided with the disappearance of many territories, many countries, beneath the ocean.” After a great blackout led to global collapse “worse than an earthquake or the eruption of a volcano,” what is left is “just infertile earth and false trees.” Phones and the internet are things of the past, replaced by “[b]lack screens and silence.” Even inside the House of the Sacred Sisterhood, environmental threats loom, from a toxic haze that sweeps the landscape to insects with legs that burn human flesh.

Yet it is in the supposed refuge of the sisterhood that Bazterrica distinguishes her sinister world. The religious order, with its devout and self-flagellating sisters, mutilates its “Chosen” and punishes the “unworthy” who aspire to rise through the ranks. There are no human meat factories here, like in Bazterrica’s past work, but the slim novel, rife with body horror, is not for the faint of heart. (I will spare you the descriptions of sewn eyelids and mutilated cockroaches.)

It’s unclear what this is all for and what really holds the community together. But, as is often the case, a rotten patriarchy lies at its core. Amid this merciless landscape, the narrator writes in secret, desperate to recover memories of her life before the sisterhood and tease out what is actually taking place in the fallen society that humans have once again created after the flood.—Chloe Hadavas

March Releases, in Brief

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count—her first novel in more than a decade—weaves together the stories of four women with ties to Nigeria and Guinea. In Sister Europe, Nell Zink dissects the mores of Berlin’s international elite in the internet age. Sons and Daughters, the last novel by the great 20th-century Yiddish writer Chaim Grade, is finally translated into English by Rose Waldman. In The Paris Express, Irish Canadian author Emma Donoghue, famed for her 2010 novel Room, fictionalizes the 1895 Montparnasse derailment. Robots and humans exist side by side in a reunified Korea in Silvia Park’s debut, Luminous.

Three Tanzanians come of age at the turn of the 21st century in Theft, Abdulrazak Gurnah’s first novel since he won the Nobel Prize in 2021. In Moroccan American writer Laila Lalami’s dystopian The Dream Hotel, surveillance capitalism encroaches on personal freedoms. An unexpected guest washes ashore on an island off the coast of Antarctica in Australian author Charlotte McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore. The late Yuko Tsushima’s Wildcat Dome, a literary mystery set in postwar Japan, is translated into English by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda. And Irish writer Colum McCann delves into the interconnected world of underwater cables in Twist.—CH

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Chloe Hadavas is a senior editor at Foreign Policy. X: @Hadavas

Allison Meakem is an associate editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @ameakem.bsky.social X: @allisonmeakem

More from Foreign Policy

-

Samuel Huntington holds his hand to his chin while sitting in an office. Samuel Huntington Is Getting His Revenge

The idea of a global “clash of civilizations” wasn’t wrong—it was just premature.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump meets with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House on Feb. 28. The Perils of a Reality TV Presidency

The Trump-Zelensky shouting match is a reminder that international diplomacy was never meant to be carried out in front of billions of eyes.

-

A Ukrainian serviceman trains in the woods near the frontline in Ukraine. Three Years On, What’s Next for Europe and Ukraine?

Nine thinkers on the bombshells coming out of Washington.

-

Donald Trump is seen inside a helicopter at night looking down at a cell phone Trump’s New Map

America’s first post-literate president has only geography to fall back on.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.