Why Don’t Russian Soldiers Revolt?

Why Don’t Russian Soldiers Revolt?

Astonishing death rates and brutal abuse have not kept troops from following orders.

Russian military cadets rehearse marching in a parade in central St. Petersburg, Russia, on on April 23, 2024. Olga Maltseva/AFP via Getty Images

Russia’s horrific casualties in its invasion of Ukraine, now estimated to have surpassed the combined total from all of Moscow’s wars since 1945, have put its infamous “meat grinder” tactics in the spotlight. Ukrainian soldiers have described waves of poorly armed, ill-prepared Russian troops thrown into battle as cannon fodder, leading to extreme rates of death and injury among the invaders. At the same time, Russian soldiers have themselves engaged in extreme violence—not only against Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war, but also against each other.

Why are Russian troops, who are treated by their commanders as “disposable infantry,” willing to put up with and engage in such widespread brutality with so little protest? Fratricidal coercion, violence within units, and mistreatment among soldiers are not unique to the Russian military, but they have seldom been seen on this scale in recent decades. And while soldiers throughout history have resisted orders—most famously, U.S. soldiers engaged in so-called fragging against their officers during the Vietnam War—this sort of defiance is largely absent among Russian troops. The ongoing invasion of Ukraine, uniquely documented through widespread online coverage, reveals how an ingrained culture of violence in the Russian military fuels a brutal cycle of coercion and complicity.

Russia’s horrific casualties in its invasion of Ukraine, now estimated to have surpassed the combined total from all of Moscow’s wars since 1945, have put its infamous “meat grinder” tactics in the spotlight. Ukrainian soldiers have described waves of poorly armed, ill-prepared Russian troops thrown into battle as cannon fodder, leading to extreme rates of death and injury among the invaders. At the same time, Russian soldiers have themselves engaged in extreme violence—not only against Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war, but also against each other.

Why are Russian troops, who are treated by their commanders as “disposable infantry,” willing to put up with and engage in such widespread brutality with so little protest? Fratricidal coercion, violence within units, and mistreatment among soldiers are not unique to the Russian military, but they have seldom been seen on this scale in recent decades. And while soldiers throughout history have resisted orders—most famously, U.S. soldiers engaged in so-called fragging against their officers during the Vietnam War—this sort of defiance is largely absent among Russian troops. The ongoing invasion of Ukraine, uniquely documented through widespread online coverage, reveals how an ingrained culture of violence in the Russian military fuels a brutal cycle of coercion and complicity.

There have been various attempts to explain docility among the Russian rank and file. Many focus on the financial incentives created by the war, including exorbitant enlistment bonuses (worth many times the average annual wage in some regions), soldiers’ salaries above the median wage, and compensation for families in case of death. Some observers have advanced sweeping cultural theories, suggesting that Russians are beset by a unique fatalism and nihilism. Others have argued that soldiers’ motivations may stem from a genuine belief in the conflict. Marlene Laruelle and Ivan Grek, Russia specialists at George Washington University, have argued that the war provides an opportunity for the “restoration of male self-worth” in a deeply dysfunctional society, creating a scenario through which “millions of Russians at the bottom of the social ladder can emerge as the country’s true heroes, ready for the ultimate sacrifice.”

But while financial and ideological factors help explain why Russians choose to enlist, they do not account for the continued acquiescence of soldiers once they face the meat-grinder tactics and systematic acts of violence perpetrated by their superiors and peers. Although some soldiers desert, the true number remains unclear. Many of those listed as AWOL are actually casualties, while other missing troops eventually return to their units. Nevertheless, most soldiers maintain a relative quiescence as they continue to face high casualty rates, a lack of equipment, and widespread mistreatment by commanders and fellow soldiers.

Soldiers’ compliance with such high levels of casualties and brutality can best be understood as a product of the pervasive and deeply ingrained culture of violence within the Russian military. This culture perpetuates a cycle that instills obedience and reinforces violence—as both victims and perpetrators—as part of a soldier’s identity. Repeated exposure to brutality, which is treated as normal and starts as soon as soldiers join the military, breaks down some of them to such an extent that they accept the tactics of their commanders without question. Brutal routinized hazing, extreme punishments, and other excessive violence is so routine that it becomes second nature to many Russian soldiers, enabling them to continue the cycle of extreme violence against Ukrainians and their own side alike.

Most militaries employ controlled, sanctioned forms of violence to prepare soldiers for the stresses of combat and to foster unit cohesion. For instance, the British Army’s Parachute Regiment engages in “milling,” which requires recruits to exchange repeated punches to the head. When unsanctioned hazing does occur in Western armies, efforts are typically made to combat it. In the Russian military, however, a particularly brutal tradition of hazing known as dedovshchina has been institutionalized into its very culture. This form of barracks violence, which occurs during the first part of a conscript’s military service, stands out for its severity and has become a central aspect of Russian military identity-building.

Within this system, recruits learn to endure and later carry out violence, becoming both its victims and perpetrators. Soldiers’ accounts describe treatment by senior conscripts involving extortion, beatings, and rape. Some have reported being forced into prostitution by senior officers. In one notorious case in the mid-2000s, a soldier was abused to such an extent that his legs and genitalia had to be amputated. In another, from 2018, a conscript allegedly killed himself after a demeaning expletive was cut into his forehead with a razor blade.

According to human rights activists, many suspicious suicides in the Russian military are linked to hazing and extortion, with some deaths suspected of being disguised as suicides to conceal murder. (The Russian military does not release official statistics on deaths among its ranks.) In 2019, a conscript stationed in Siberia opened fire on his unit, killing eight people, later explaining that he was driven to the act by the abuse that he suffered at the hands of his unit.

In Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this deeply ingrained culture of violence persists—even though many soldiers are sent to fight on the front lines almost immediately after conscription or enlistment, leaving little time for training and for the typical cycle of dedovshchina to unfold.

Violence against and among soldiers continues to be a mechanism to maintain obedience. Russia has reportedly used barrier troops to kill or otherwise stop its own soldiers from retreating. Those who complain, step out of line, or ask to leave have been forced into “punishment pits,” placed in detention centers, or executed by their commanders. Outside the battlefield, drunken soldiers have killed civilians and each other. Indeed, soldiers turn on each other at rates we would not expect from a well-organized military; in an extreme case, a group of Russian soldiers tortured a fellow soldier to death after he attempted to curb their drinking and misbehavior. All this violence endures with relative impunity. When soldiers are extrajudicially executed or otherwise killed, their deaths have been disguised as combat casualties or desertion.

The Russian military’s use of violence against its own creates a cycle of behavior in which violence is routinized and internalized, conditioning soldiers to accept it as the norm and undermining their ability and will to dissent—whether out of fear, resignation, or the normalization of violence itself. Indeed, violence becomes a building block of soldiers’ identities, expectations, and self-expression. It’s an enduring legacy that spans generations: Both the Russian and Soviet armed forces have historically used fear and violence against their own recruits, civilians, and opposing soldiers in order to terrorize these groups into obedience or capitulation, respectively.

The result is twofold. Given their exposure to extreme violence and their inability to organize mass resistance, some soldiers feel powerless against the military, ultimately resigning themselves to their circumstances—whether those circumstances are being ordered to commit war crimes or deploy in a suicide attack—with minimal active resistance. While some might complain about their situations, most do not. This large-scale quiescence stems not from an acceptance of the military’s culture of violence, but rather from a fear of the consequences that it enforces. Knowing that the consequences of any dissent will be extreme, soldiers comply out of self-preservation, offering little resistance even when given orders that will all but certainly lead to death.

For another group of soldiers, however, this legacy of and repeated exposure to violence teaches them not only to acquiesce to violence, but also to actively participate in it, even to the extent that they defy the rules of war. Those who do engage in such brutality, such as one of the brigades accused of committing war crimes in Bucha, are often rewarded by the Russian government, which further normalizes and entrenches lethal violence in the Russian ranks.

Conditioned by a brutal military culture, Russian soldiers are trapped in a cycle of violence from which they are unlikely to break free. This has profound implications for the country’s invasion of Ukraine, now in its fourth year. First, since astonishingly high casualty rates have not prevented Russian soldiers from following orders, Russia is likely to continue its war of attrition, with Ukrainian soldiers facing more waves of supposedly disposable Russian soldiers sent to the front. Second, Russian soldiers will persist in their systematic repression of Ukrainians, committing human rights abuses and war crimes against civilians and prisoners-of-war.

As the world knows from the liberation of Bucha and Irpin—and from numerous testimonies of survivors of Russian violence—the Russian military continues to follow its policy of extreme brutality. Far from giving soldiers second thoughts about fighting, their own side’s violence only encourages them to follow along and perpetrate more of it.

Amelie Tolvin is a visiting scholar at the University of Helsinki’s Aleksanteri Institute for Russian and Eastern European Studies as well as a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Toronto. Bluesky: @atolvin.bsky.social

More from Foreign Policy

-

American flags are draped around tables and pipes in a small factory room as women work at sewing machines to produce them. Tariffs Can Actually Work—if Only Trump Understood How

Smart trade policy could help restore jobs, but the president’s carpet-bomb approach portends disaster.

-

Donald Trump looks up as he sits beside China’s President Xi Jinping during a tour of the Forbidden City in Beijing on Nov. 8, 2017. Asia Is Getting Dangerously Unbalanced

The Trump administration continues to create headlines, but the real story may be elsewhere.

-

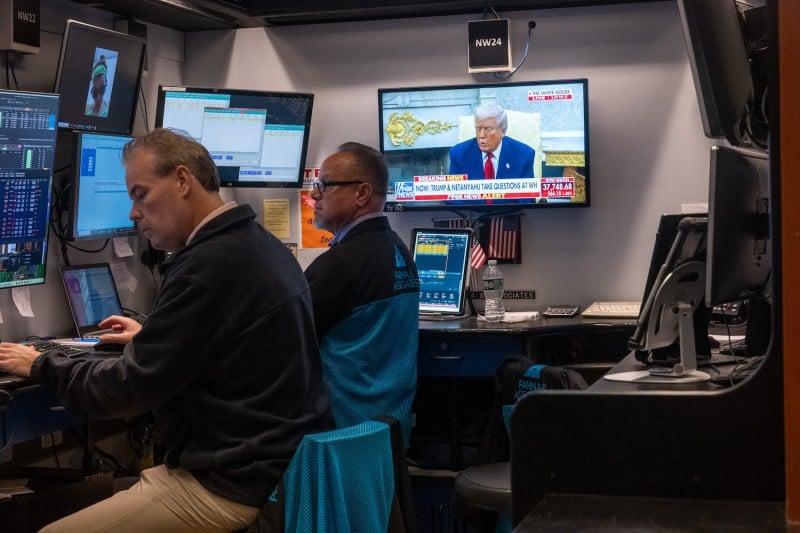

Trump announces tariffs Trump’s Wanton Tariffs Will Shatter the World Economy

Economic warfare is also a test for U.S. democracy.

-

The Department of Education building in Washington, DC on March 24. Why Republicans Hate the Education Department

Broad popular support means that even Ronald Reagan failed at dismantling the agency.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.