South Korea’s Far Right Has Been Terrifyingly Radicalized

South Korea’s Far Right Has Been Terrifyingly Radicalized

The impeachment of martial law President Yoon Suk-yeol reveals how far the rot spread.

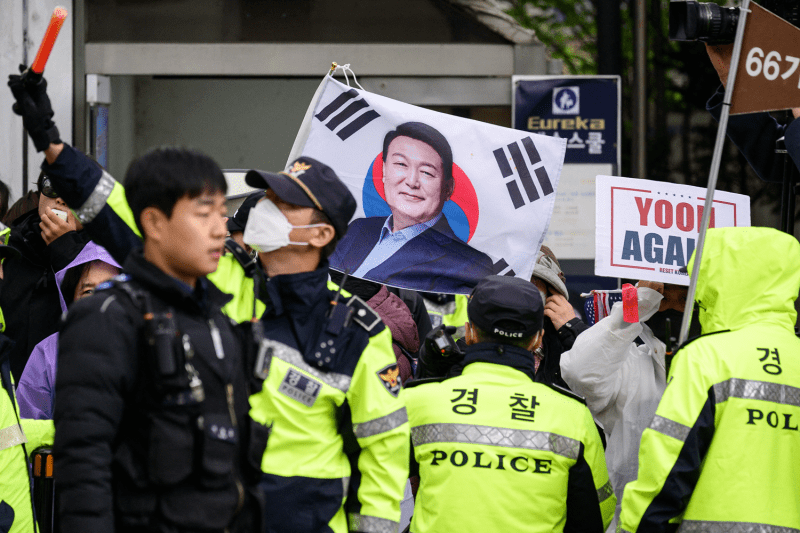

Police stand in front of supporters on the side of a road as they wait for the arrival of former South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol (pictured on flag) outside the Central District Court in Seoul on April 14. Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images

On April 4, South Korea’s Constitutional Court unanimously voted to sustain Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment, removing him from the presidency for his illegal declaration of martial law and attempted autogolpe on Dec. 3, 2024. Yoon’s bizarre and short-circuited presidency displayed many of the antidemocratic trends emerging around the world. South Koreans’ response, in turn, offers an example of the way forward.

The Yoon administration was a strange one from the start. Having won on March 9, 2022—in the narrowest victory in South Korean presidential election history—by pandering to grievances about the rising cost of housing as well as young men’s toxic misogyny, Yoon’s first major initiative as the president was to relocate the presidential office from the Blue House—the presidential residence—to the Defense Ministry compound.

On April 4, South Korea’s Constitutional Court unanimously voted to sustain Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment, removing him from the presidency for his illegal declaration of martial law and attempted autogolpe on Dec. 3, 2024. Yoon’s bizarre and short-circuited presidency displayed many of the antidemocratic trends emerging around the world. South Koreans’ response, in turn, offers an example of the way forward.

The Yoon administration was a strange one from the start. Having won on March 9, 2022—in the narrowest victory in South Korean presidential election history—by pandering to grievances about the rising cost of housing as well as young men’s toxic misogyny, Yoon’s first major initiative as the president was to relocate the presidential office from the Blue House—the presidential residence—to the Defense Ministry compound.

The move was supposedly done to make the presidency more approachable, but it only served to amplify the whispers about Yoon’s superstitions. Shamans—traditional Korean magical practitioners who have become closely associated with the right wing—have reportedly claimed that the Blue House was cursed.

Absence of good or even ordinary governance under Yoon caused mundane events to spiral into mass-casualty disasters. One of the disasters—the crowd-crush incident in the Itaewon district of Seoul that killed 159 in October 2022—partly stemmed from the Blue House move, as police officers later testified that they were stretched too thin protecting his new residence to provide proper crowd control.

During the 2022 monsoon season, the government no longer had easy access to the state-of-the-art National Crisis Management Center located in the Blue House’s underground bunker, where a South Korean president would normally oversee a disaster response. Instead, Yoon was trapped in his own home by the flood, and Interior Minister Lee Sang-min took hours to reach a backup location while dozens died.

Coupled with the wobbly economy, Yoon’s approval rating soon cratered as low as 23 percent, making him the least popular president in South Korean history. But rather than making compromises to enlarge his coalition, Yoon undermined his own base by axing allies whom he deemed insufficiently loyal.

Lee Jun-seok, a young conservative legislator who was crucial in forming the strategy to fuel the youth’s right-wing turn by stoking misogyny, was unceremoniously pushed out of the party leadership in July 2022—just a few months after the presidential election—in favor of the leadership that was more pliant to Yoon. Han Dong-hoon, Yoon’s justice minister and longtime capo who was presumed to be next in line for presidency, was cut off in 2024 after daring to suggest that Yoon’s wife should be investigated for numerous allegations of white-collar crimes, including schemes where her alleged co-conspirators had been found guilty.

In the legislative election in April 2024, Yoon and his People Power Party suffered a thumping defeat, leaving them with only 108 out of 300 seats. The opposition Democratic Party used its supermajority to great effect, passing a series of special prosecutor investigation bills, impeaching some of Yoon’s most loyal toadies in the bureaucracy (such as Lee Jin-suk, the chief of Korea Communications Commission, who acted as Yoon’s media enforcer), and slashing the budget for the presidential office’s discretionary fund.

In response, Yoon launched the self-coup, attempting to end democracy altogether.

The court decision sustaining Yoon’s impeachment should not obscure how close he was to success and the horror that would have followed if he did achieve martial law. The subsequent investigation revealed that Yoon and his government were planning to goad a North Korean attack to use an excuse to declare martial law. The fate of South Korea’s democracy hinged on North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s restraint as Yoon’s Defense Ministry flew drones over Pyongyang skies, trying to start a war.

The Hankyoreh, a liberal newspaper based in Seoul, reported in mid-February that it had obtained a notebook found at the home of former Gen. Noh Sang-won, who has been arrested on charges of aiding the insurrection attempt. (Noh has denied the charges and any connection to Yoon.) The newspaper reported that the notebook detailed a terrifying plan—a “kill list” with the names of politicians, including Yoon’s former right-hand man Han, as well as judges, journalists, labor leaders, and clergy, totaling between 5,000 to 10,000 people, to be “disposed of.”

The Hankyoreh also reported that oh, who was previously the head of military intelligence but was running a fortune- telling service after being discharged in 2018, wrote that these individuals should be rounded up and killed in an incident that would be seen as accidental, for example by putting them on a boat that would self-destruct in the middle of the ocean.

The notebook also detailed a plan for Yoon to stay in power for at least three terms. Yoon and the military would establish an alternate legislature to replace the noncompliant National Assembly and install a new constitution that would allow Yoon to remain in power for several presidential cycles, modeled after Chinese and Russian election system.

Yoon’s presidency was emblematic of disturbing trends worldwide. Yoon himself, as well as his supporters, were completely beholden to an alternate reality constructed largely through far-right YouTube channels, which constantly blared paranoid and baseless claims that North Korea and China had infiltrated the South Korean government to rig the 2024 elections in favor of liberals.

In his coup attempt, Yoon directly acted on this conspiracy theory by sending a military detachment to the National Election Commission (NEC), seeming to be utterly confident that he would discover evidence of the supposed election fraud that would convince the country of the necessity for his martial law decree.

During the impeachment trial, the prosecution alleged that Noh, Yoon’s liaison with the country’s military community, had prepared cable ties and eye masks with which to kidnap the NEC officials, as well as possible torture devices such as baseball bats, hammers, and pliers. The NEC officials were to be taken to a military bunker, where they would be interrogated and tortured until they confessed the election fraud.

Yoon’s loyal followers were likewise radicalized—through digital platforms such as YouTube—into a total rejection of democracy. An in-depth study conducted in February by SisaIn magazine showed that approximately 40 percent of self-identified South Korean conservatives supported Yoon’s martial law and opposed his impeachment.

Within this group, 42 percent agreed with the statement that “a strong leader sometimes has to break the rules to achieve his goals,” 65 percent agreed that “a controversial ruling by a liberal judge does not have to be followed,” and 55 percent agreed that “violence is justified because Korean democracy is in crisis.”

A propensity for YouTube is directly correlated to antidemocratic attitudes in South Korea. Respondents who watched more than an hour a day of far-right YouTube content tended to agree that Yoon’s declaration of martial law was justified (68 percent), that Yoon should not be impeached (74 percent), that the mob attack on the Seoul Western District Court after Yoon’s arrest was a justified case of citizens exercising their right to resist (63 percent), that they would not accept a Constitutional Court decision removing Yoon from office (68 percent), that China had interfered with South Korean elections (66 percent), that a Supreme Court decision finding no evidence of Chinese interference should not be trusted (75 percent), and that a victory by Democratic Party in the next presidential election would lead to South Korea becoming communist (78 percent) and being colonized by China (73 percent).

This brain rot has gone global. Wealthy Korean Americans such as Annie Chan, a real estate magnate, have bankrolled far-right groups in both the United States and South Korea, fostering an international community of conspiracy theorists. Chan’s group, Korea Conservative Political Action Coalition, was a prominent presence in annual meeting of the Conservative Political Action Convention held in February 2025 near Washington, D.C., pleading Yoon’s case to the Nazi-saluting supporters of U.S. President Donald Trump. Matt Schlapp, a former White House political affairs director during Trump’s first term, was seen meeting with Yoon at the presidential residence in Seoul shortly after Yoon’s impeachment.

Nevertheless, the impeachment and removal of Yoon show that South Korean democracy persevered—a cause for hope. Although a narrow majority elected Yoon, the South Korean public decisively reacted against the former president’s attempt to subvert democracy, notwithstanding the loud minority that continued to support the impeached president.

The lasting images from this chapter of South Korean history will be those of Lee Jae-myung, the leader of the Democratic Party, and Woo Won-sik, the speaker of the National Assembly. On the night of Dec. 3, 2024, when Yoon declared martial law, Lee did not run and hide—although as the opposition leader, he knew that he could be the first to be arrested and disappeared. Instead, he rushed to the National Assembly Hall while using a live video feed to urge the public to join him through.

At the legislature building, Lee was joined by the 67-year-old Woo, who jumped a wall to enter the building to avoid the police and the military. In what some commentators have called “a reverse Jan. 6,” ordinary people answered Lee’s call, throwing their bodies in front of armored cars and forming a human wall around the National Assembly Hall as the lawmakers voted to dissolve the martial law decree.

Even as paratroopers began streaming into the building and the legislative aides fought back with fire extinguishers and cellphone flashes, Woo emphasized that proper parliamentary procedures must be followed to dissolve the martial law decree. After 12 agonizing minutes of typing up the bill and submitting it, the National Assembly voted to dissolve the martial law decree, eventually prompting the end of Yoon’s presidency on April 4.

Democracies around the world are facing a crisis. A “burn it all down” attitude is rampant—mostly among the far right, but also from many in the left—calling for revolutionary destruction of a system that appears to have abandoned ordinary people. Meanwhile, others simply tune out politics, thinking that it is no longer relevant to their lives and ceding the civil society to the shrill acrimony of the most radical voices.

South Korea’s response offers an alternative. The public has not given into apathy. In the face of dictatorship, the people participated directly by giving heroic resistance to the attempt to end democracy with guns.

Yet their action was intended not to destroy the system, but to preserve it—to allow the legislators to vote down the martial law and urge the justices to uphold the constitution.

The South Korean experience shows that a democracy need not choose between nihilistic destruction and listless anemia. A democracy can be based on norms, institutions, and procedures—all of which are energized by the people’s willingness to stand in front of guns and tanks.

S. Nathan Park is a Washington-based attorney and nonresident fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

More from Foreign Policy

-

American flags are draped around tables and pipes in a small factory room as women work at sewing machines to produce them. Tariffs Can Actually Work—if Only Trump Understood How

Smart trade policy could help restore jobs, but the president’s carpet-bomb approach portends disaster.

-

Donald Trump looks up as he sits beside China’s President Xi Jinping during a tour of the Forbidden City in Beijing on Nov. 8, 2017. Asia Is Getting Dangerously Unbalanced

The Trump administration continues to create headlines, but the real story may be elsewhere.

-

Trump announces tariffs Trump’s Wanton Tariffs Will Shatter the World Economy

Economic warfare is also a test for U.S. democracy.

-

The Department of Education building in Washington, DC on March 24. Why Republicans Hate the Education Department

Broad popular support means that even Ronald Reagan failed at dismantling the agency.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.