Is the world losing faith in the almighty US dollar?

On August 15 1971, President Richard Nixon interrupted an episode of Bonanza to announce “a new economic policy” to American families gathered in front of their television sets that Sunday evening. Among the myriad measures the president outlined was a 10 per cent import tariff — and the suspension of the US dollar’s convertibility into gold.

Nixon himself was more worried about the political backlash from Americans expecting to spend their evening with the Cartwright family at Ponderosa Ranch than the nefarious “international money speculators” his announcement targeted. Yet the consequences were enormous. Although couched as a temporary measure, the US would never again return to the so-called gold standard.

What became known as the “Nixon shock” marked the end of one financial era and the beginning of a new one. The global monetary framework thrashed out at the Mount Washington Hotel in New Hampshire’s Bretton Woods in 1944 — with the gold-backed US dollar as the Sun around which every other currency circled — was dead.

The Nixon shock helped usher in a new age of freely traded floating currencies, rapid credit creation and global capital flows, untethered by gold and increasingly unrestricted by governments.

More than half a century later, the world is grappling with a shock of similar magnitude. Earlier this month the US administration of Donald Trump unveiled an aggressive tariff regime where both the size of the levies and the facile methodology underpinning them shocked even many supporters.

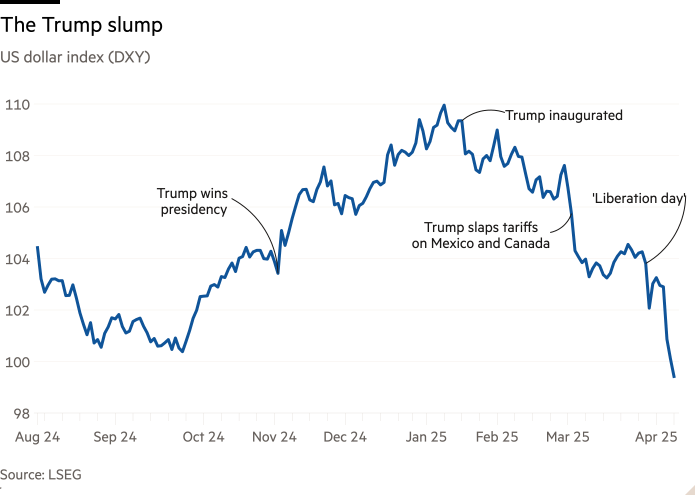

Faced with a revolt in financial markets, the president announced a 90-day partial pause, but investors remain on edge. The dollar, which normally strengthens at times of financial and economic strife, has instead nosedived.

Coming amid an increasingly bellicose attitude towards historical allies and an ambivalent attitude to the dollar’s hegemony by some key figures in the administration, it has forced investors and analysts around the world to confront the possibility of a new era where the US dollar’s dominance might fade — or even end.

“The trade war is just the latest example of this administration’s contempt for the rest of the world,” says Mark Sobel, US chair of OMFIF, a financial think-tank, and a former senior Treasury official. “Being a trusted partner and ally is a key pillar of the US dollar’s dominance, and has been tossed to the wind.”

There are two related but subtly different questions now being asked around the world’s financial centres after this “Trump shock”. First, how far can the dollar’s recent decline go? Foreigners own $19tn of US equities, $7tn of US Treasuries and $5tn of US corporate bonds, according to Apollo’s chief economist, Torsten Sløk. If even some of these investors start to trim their positions, the dollar’s value will come under sustained pressure.

Second, if the outflows gather pace, could it eventually even erode the dollar’s unique role in the global economy and financial system? Although the dollar’s value has always waxed and waned, and critics have constantly sought to tear it down, the greenback’s primacy has remained undiminished. Yet some analysts and investors now think the scale of the Trump shock could end a near-century of dollar dominance.

“The US has benefited from reserve currency status for 100 years. It’s taken less than 100 days to unwind it,” says Gregory Peters, co-chief investment officer at PGIM Fixed Income. “It’s a very big deal.”

When Nixon’s Treasury secretary, John Connally, attended a G10 meeting in Rome shortly after the US ended the dollar’s convertibility, the bombastic Texan told his shocked international counterparts: “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

The Trump administration’s view is the opposite: the dollar is everyone’s currency, but America’s problem. And this is not as perverse as it might seem.

Despite Nixon severing the dollar’s link to gold in 1971, the greenback has remained at the centre of the monetary universe. In fact, thanks to the dollar’s importance in the expanding and increasingly interconnected global financial system, its importance has only grown. Far from eroding the dollar’s importance, the Nixon shock entrenched it in new ways.

Nowadays, the US only accounts for about a quarter of the global economy, but more than 57 per cent of the world’s official foreign currency reserves are in dollars, according to the IMF. While much has been made of its relative decline in central bank reserves over the past few decades, the reserves statistics arguably underplay the dollar’s centrality. There are many other pots of sovereign and quasi-sovereign money that are not captured by the IMF’s data on foreign exchange reserves, and whether you are a bank in Mongolia, a pension plan in Chile, a European insurance group or a Singaporean hedge fund, dollars are the ultimate reserve asset.

The dollar is equally central in trade, with 54 per cent of all export invoices denominated in dollars, according to the Atlantic Council. In finance, its dominance is even more total. About 60 per cent of all international loans and deposits are denominated in dollars, and 70 per cent of international bond issuance. In foreign exchange, 88 per cent of all transactions involve the dollar.

Even physical US bank notes are widely held abroad, thanks to the dollar’s broad acceptance. In fact, about half of the more than $2tn worth of US bank notes in issue are held by foreigners, according to the Federal Reserve.

This enormous international demand for dollars translates into an embedded premium to US assets and means that the US borrows more cheaply than it would otherwise do — what France’s former president, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, once famously referred to as America’s “exorbitant privilege”. It also gives the US the power to sabotage another country’s financial system through sanctions.

However, many in the Trump administration argue that the costs of the dollar’s reserve status outweigh the benefits, by making the US currency unduly strong and hurting American exporters.

“While it is true that demand for dollars has kept our borrowing rates low, it has also kept currency markets distorted,” Stephen Miran, chair of the Trump administration’s Council of Economic Advisers, said in a speech last week. “This process has placed undue burdens on our firms and workers, making their products and labour uncompetitive on the global stage.”

Whether by accident or design, almost every action taken by the Trump administration in its first three months has hammered at the dollar’s support. Last week the DXY dollar index — which measures the strength of the currency against a basket of its biggest peers — fell 2.8 per cent. This was its seventh-worst week in the past three decades. It has kept dipping this week, extending its 2025 decline to 8.2 per cent.

“It’s not just that you can’t trust the US any more, be it on geopolitics or trade,” says an American finance executive. “We have also managed to massively piss off the rest of the world. There’s genuine, personal animosity towards us, and that hurts the dollar.”

Most notably, the dollar has been particularly weak against other “haven” currencies that typically strengthen when markets are turbulent, such as the Swiss franc and the Japanese yen, and against gold. That the greenback is seemingly being excluded from this select club of currencies is a shocking development to many analysts and investors.

“Despite President Trump’s reversal on tariffs, the damage to the USD has been done,” George Saravelos, global head of foreign exchange research at Deutsche Bank, wrote in a report last Friday. “The market is reassessing the structural attractiveness of the dollar as the world’s global reserve currency and is undergoing a process of rapid de-dollarisation.”

Nonetheless, most analysts say that the dollar’s reserve status is unlikely to end, simply because of a paucity of feasible replacements. The euro is one monetary union but 20 different countries, China keeps the renminbi on a tight leash, limiting its convertibility, and currencies such as the Swiss franc and Japanese yen are far too small to be contenders. To adapt a well-worn cliché, the dollar is not only the least smelly shirt in the closet, it is the only one that fits.

“The dollar’s dominance will remain in place for the foreseeable future because there are no viable alternatives,” predicts Sobel at the OMFIF. “I question whether Europe can get its act together, and China is clearly not opening its capital account any time soon. So what’s the alternative? There just isn’t one.”

Moreover, the dollar’s dominance is so thoroughly embedded into the fabric of the global economy, thanks to a complex multitude of independent but interlocking factors, that even the Trump administration is unlikely to be able to fundamentally alter the status quo.

Nonetheless, even though the dollar’s unique role may be sustained by inertia and a lack of alternatives, it can still lose value. Despite its declines in April, the DXY dollar index is still 12 per cent higher than it was at its lows in 2020, and almost 40 per cent over its nadir in early 2008. Many foreign exchange analysts are now ripping up their previous forecasts and predicting further falls for the dollar.

For example, Goldman Sachs — previously optimistic on the dollar — now predicts the US currency will fall to $1.20 against the euro and ¥135 against the Japanese yen over the next 12 months, equivalent to another 6 per cent weakening from the current levels. “The negative trends in US governance and institutions are eroding the exorbitant privilege long enjoyed by US assets, and that is weighing on US asset returns and the dollar, and may continue to do so in the future unless reversed,” Goldman’s foreign exchange analysts warned.

The longer-term trajectory is more uncertain. Bill Dudley, the former head of the New York Federal Reserve, argues that the US currency could even strengthen. Tariffs will weaken both weaken the US economy and fuel inflation, while elsewhere the impact on economic growth is likely to be far more pronounced, Dudley argues. That means other central banks are likely to cut interest rates more aggressively than the Fed, and could lead those currencies to weaken against the dollar.

Others are more pessimistic. Stephen Jen, a longtime foreign exchange strategist and the head of Eurizon SLJ Capital, has long pointed out that a lot of macroeconomic oddities — such as the average dollar income of Mississippi, America’s poorest state, being comparable to Germany and the UK, and markedly higher than that of Japan — are best explained by a “grossly” overvalued dollar.

Jen estimates that the dollar is about 19 per cent overvalued against its main peers, and suggests that it could weaken even beyond this if the US economic downturn is so strong that it forces the Federal Reserve to aggressively cut interest rates. Then, cyclical, structural and political forces would all conspire to meaningfully weaken the greenback.

“The stars are aligning for the dollar to embark on a multiyear correction,” Jen wrote in a letter to clients last week. “The dollar’s overvaluation has been one factor contributing to the US’ loss of competitiveness over the years, and the burgeoning trade deficit and tariffs are a reaction to this unpleasant reality.”

For critics of the Trump administration, that the White House started April by celebrating “National Financial Literacy Month” was in retrospect archly appropriate, given the widely mocked “reciprocal” tariff methodology unveiled the very next day, and the mayhem that subsequently unfolded.

The US government’s subsequent partial suspension of this new tariff regime has restored some order to the stock market, and over the weekend it exempted smartphones and some other consumer electronics from tariffs — including those imported from China. That has encouraged some investors to think that the final outcome might not be as bad as initially feared.

Nonetheless, many analysts caution that the Trump administration’s willingness, even eagerness, to upend norms means that previously unthinkable issues are now being openly discussed. These range from concrete dangers, such as whether the Federal Reserve’s independence is under threat, to suggestions that once would have been considered fantasy — such as whether the US could impose levies on Treasury purchases, capital controls, withdraw from organisations such as the IMF, or even threaten selective debt defaults.

“These are shocking questions, but they are now being asked,” says Ajay Rajadhyaksha, chair of global research at Barclays. “We can’t close our eyes to that.”

This means that a gradual investor exodus may be inevitable even if the Trump administration continues to back down from the bellicose positions staked out in its first three months. “Our real concern is that while Trump may be able to cut a few tariff deals, when the issue is a broader loss of confidence in the United States, even a much fuller retreat on trade might not work,” argues Sarah Bianchi, a senior analyst at Evercore ISI, a US investment bank.

As Walter Wriston, the late Citicorp boss who was one of the titans of American banking, once observed: “Capital goes where it is welcome and stays where it is well treated.” For close to a century, the US has been the world’s ultimate destination for money. Now, investors suddenly worry this may no longer be true, and the ramifications could be dramatic.