How India Alienated Bangladesh

How India Alienated Bangladesh

Due to strategic myopia, New Delhi faces a potential crisis on another border.

Indian Border Security Force personnel stand guard at the India-Bangladesh border at the Fulbari outpost near Siliguri, India, on May 9. Diptendu Dutta/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images

In June 2017, Indian and Chinese troops stared each other down on the windswept Doklam plateau in Bhutan, beginning a standoff that lasted for 73 days. The trigger was a Chinese road construction project that came perilously close to India’s vulnerable Siliguri Corridor—sandwiched between Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal—and brought home a chilling reality: The fate of India’s northeast could hinge on this sliver of land and the goodwill of its neighbors.

That vulnerability is now back in the conversation, not because of Chinese action, but because of a dramatic shift in Bangladesh’s foreign policy. In just a few months, India-Bangladesh ties have unraveled into mutual suspicion, strategic maneuvering, and a dangerous blame game. Since Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s ouster last August, New Delhi has lost its privileged access in Dhaka, where the new leadership is openly courting Beijing and Islamabad.

In June 2017, Indian and Chinese troops stared each other down on the windswept Doklam plateau in Bhutan, beginning a standoff that lasted for 73 days. The trigger was a Chinese road construction project that came perilously close to India’s vulnerable Siliguri Corridor—sandwiched between Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal—and brought home a chilling reality: The fate of India’s northeast could hinge on this sliver of land and the goodwill of its neighbors.

That vulnerability is now back in the conversation, not because of Chinese action, but because of a dramatic shift in Bangladesh’s foreign policy. In just a few months, India-Bangladesh ties have unraveled into mutual suspicion, strategic maneuvering, and a dangerous blame game. Since Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s ouster last August, New Delhi has lost its privileged access in Dhaka, where the new leadership is openly courting Beijing and Islamabad.

As India struggles to shape the global narrative after its recent clash with Pakistan, having its eastern neighbor aligned with its two biggest adversaries—to the west and the north—is not welcome news.

India’s troubles with Bangladesh are not the result of a hostile axis between China and Pakistan, but because of its own missteps: most notably, New Delhi’s unwavering support for Hasina’s authoritarian regime and the rise of Hindu nationalism under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. By prioritizing short-term security interests and domestic politics over democratic values and goodwill, India alienated the Bangladeshi public, squandered its influence in Dhaka, and pushed its neighbor to seek out new partners.

Meanwhile, Indian media is awash with alarmist rhetoric that frames Bangladesh’s pivot as a conspiracy orchestrated by China and Pakistan. The truth is that India’s predicament is largely self-inflicted, the result of years of strategic myopia. The diplomatic rupture threatens India’s security, economic interests, and regional standing—underscoring the urgent need for introspection and a reset in New Delhi’s approach to its neighborhood.

Few places illustrate India’s strategic vulnerability more starkly than the Siliguri Corridor, which is 22 kilometers wide at its narrowest point and connects India’s northeast to the rest of the country. The corridor is a lifeline to the Indian states bordering China and Myanmar.

Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh’s interim leader, did not mince words about the area during a visit to China in March, drawing outcry in New Delhi. He urged China to establish an economic foothold in Bangladesh by highlighting his country’s strategic position. “India’s northeast is completely landlocked, and its access to the ocean is completely controlled by Bangladesh. The Siliguri Corridor is the only route that connects the northeast with the rest of India, and this connection passes through Bangladesh,” Yunus said.

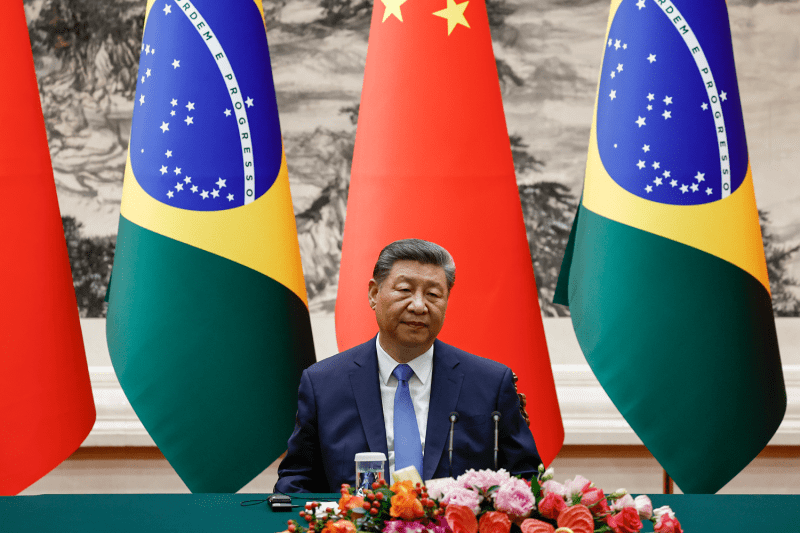

In China, Yunus showed a new willingness to leverage geography for diplomatic and economic advantage. This wasn’t just rhetoric: Chinese President Xi Jinping sent a plane to bring Yunus to Beijing, signaling close ties. China also granted 100 percent duty-free access to Bangladeshi exports and pledged to import more goods from Bangladesh. Yunus secured a commitment of $2.1 billion in Chinese funding, along with infrastructure and military cooperation agreements.

Eager to expand its influence in South Asia, China has long embraced Bangladesh as a partner, including during Hasina’s regime, when it built a submarine base in the coastal city of Pekua. These ties are reaching another level under Yunus, while India struggles to find its footing in Bangladesh without Hasina.

India’s nightmare scenario is clear: A hostile Bangladesh, aligned with China and Pakistan, could threaten to choke off the Siliguri Corridor, isolating the northeast and destabilizing the region.

This isn’t just theoretical. When Indian soldiers boldly walked into Bhutan in June 2017 to stop Chinese workers from building a road, it was to prevent Beijing from getting close to the Siliguri Corridor. Former Indian Army Gen. M.M. Naravane mentions concern at the highest political levels about Chinese access to the region in his memoir, Four Stars of Destiny. (The Indian government has not cleared the book for publication.)

China consolidated its military presence in the Doklam plateau after the two sides disengaged in August 2017. But it remained a point of concern even in 2020, when India and China were grappling with a major border crisis in Ladakh, some 1,500 miles away. According to Naravane, India has constantly pressed Bhutan about safeguarding the area. To hear Yunus openly talk about this strategic vulnerability on Chinese soil is bound to raise an alarm in India.

Meanwhile, Yunus has also agreed to invite China to further develop the Mongla port; under Hasina’s government, Bangladesh agreed to let India use and operate the port, with operational rights for an Indian company now in place. The Bangladeshi leader has also reportedly invited Pakistan to build an air base at Lalmonirhat, near the Siliguri Corridor.

Many people in both countries pinned hopes on Modi’s meeting with Yunus at a regional summit in Bangkok in April to reset India-Bangladesh relations, but the leaders talked past each other. The meeting highlighted major flash points, as Modi and Yunus raised their grievances and security concerns, underscoring the depth of tensions and the need for further dialogue.

Yunus’s press secretary, Shafiqul Alam, posted on social media that when Yunus mentioned Bangladesh’s request for the extradition of Hasina—who has been staying in New Delhi since last year—Modi’s “response was not negative.” (Alam also said that Modi told Yunus, “We saw her [Hasina’s] disrespectful behavior towards you.”)

India, however, denied the claim and dismissed the account as politically motivated. Modi raised the issue of attacks against Hindus in Bangladesh after Hasina was deposed, and Indian officials said that the “Bangladeshi contention that attacks on minorities were a social media concoction was dismissed as being in contradiction of facts on the ground.”

For nearly two decades, India’s Bangladesh policy revolved only around Hasina. Her Awami League government delivered stability in India’s northeast, cracked down on insurgents targeting India, and granted New Delhi vital transit rights. Under Hasina, Bangladesh even gave favorable contracts to the Adani Group, a corporate ally of Modi.

In return, India provided unwavering diplomatic, political, and economic support to Hasina, even as her rule grew increasingly autocratic and unpopular. Elections in 2014, 2018, and 2024 were widely criticized as rigged. Yet India shielded Hasina from international pressure and ignored Bangladeshis’ growing resentment toward her government; it hardly engaged with other stakeholders during her tenure.

This Faustian bargain had consequences. To many Bangladeshis, India became complicit in undermining the country’s democratic aspirations. Anti-India sentiment festered, fueled by border killings, water-sharing disputes, and the perception that India benefited disproportionately from the relationship. When mass protests forced Hasina’s resignation, India found itself with few friends in Dhaka and little leverage.

Hindu nationalist politics under Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have compounded India’s woes. The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act excluded Muslims from provisions for fast-tracked Indian citizenship for persecuted minorities from Bangladesh and other neighbors. Those in Bangladesh saw the law as an affront—an attempt to cast Bangladeshis as “illegal infiltrators” and “termites,” in the words of Indian Home Minister Amit Shah.

Modi’s visit to Bangladesh in 2021 sparked violent protests, and persistent anti-Bangladeshi rhetoric from BJP leaders has deepened the sense of betrayal.

To many Bangladeshis, India now appears less as a secular partner and more as a Hindu-majoritarian state, indifferent to the concerns of its Muslim neighbors. India has raised the issue of attacks against Hindus in Bangladesh since Hasina’s ouster, often based on misinformation. In a tit-for-tat response to such statements, Dhaka recently urged New Delhi “to take all steps to fully protect the minority Muslim population” after violence in the Indian state of West Bengal.

This shift has emboldened nationalist and Islamist forces in Dhaka, who see little incentive to accommodate Indian interests and every reason to seek new partners in Beijing and Islamabad.

Indian commentary often attributes Bangladesh’s new foreign-policy activism to manipulation by China and Pakistan. The reality is more complex. Under Yunus, Bangladesh is pursuing a classic hedging strategy: broadening its diplomatic options, extracting investment from China, and re-engaging with Pakistan after years of estrangement. In April, Bangladesh and Pakistan held their first foreign office consultations since 2010. Pakistan’s deputy prime minister was scheduled to visit Dhaka afterward; it was postponed after the terrorist attack in Kashmir.

Bangladesh resuming direct flights, easing visa restrictions, and engaging in nascent military cooperation with Pakistan signal a deliberate effort to reduce dependence on India and assert autonomy. Pakistan, meanwhile, sees a chance to regain influence in Bangladesh, which it lost in the country’s 1971 liberation war, with the added benefit of unsettling India’s eastern flank.

China, for its part, has seized the opportunity. It has offered Bangladesh duty-free access for exports, technology transfers, and billions of dollars in infrastructure funding with a clear goal to draw the country into the orbit of its Belt and Road Initiative and use its territory as strategic leverage against India. China offers Bangladesh a route to “escape India’s foreign policy grip” and an opportunity for the next stage of greater regional integration.

Alarmed by these developments, India has responded with a mix of threats, intimidation, and economic coercion. Its message to Beijing, Dhaka, and Islamabad is unambiguous: Any attempt to threaten the Siliguri Corridor will be met with overwhelming force. “India has one chicken neck and Bangladesh has two chicken necks. So, if they think of attacking our chicken neck, we will attack their two necks. Their chicken neck from Meghalaya to Chittagong port is smaller than our chicken neck. It’s just one call away,” Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said.

A retired Indian naval commander wrote that a narrow land bridge in southeastern Bangladesh is vulnerable to Indian military action; there is a 17-kilometer-wide area that opens into the Bay of Bengal and includes Chittagong harbor, which could be split off from the country. A former policy advisor to Modi’s government has even advocated new mapmaking to redress a “strategic vulnerability” like the Siliguri Corridor—threatening the very existence of Bangladesh.

On the economic front, India has suspended a key transshipment facility that allowed Bangladesh to route exports through Indian ports—widely interpreted as retaliation for Dhaka’s embrace of Beijing. The arrangement had streamlined trade, making it easier and cheaper for Bangladesh to access international markets. Terminating it will likely increase costs for Bangladesh’s strained export sector, especially its garment industry.

Over the weekend, India tightened the screws when it stopped Bangladeshi exports of ready-made garments and other specified goods through all land ports, allowing entry only via Kolkata and Mumbai with mandated inspections. The move came in response to Bangladesh’s earlier restrictions on Indian yarn exports via land ports; it significantly limits Bangladeshi access to the Indian market, affecting its garment industry and broader bilateral trade relations. Though India frames these steps as necessary for national security, they also risk deepening the rift.

Blaming Pakistan and China for the current tensions conveniently ignores India’s own role in alienating Bangladesh. By backing Hasina, ignoring democratic backsliding, and indulging in Islamophobic politics, India has squandered the goodwill that it built painstakingly over decades.

The strategic consequences are profound. Bangladesh’s pivot away from India threatens to undermine counterterrorism cooperation, which is vital for containing cross-border militancy and insurgency in India’s volatile northeast. Economic ties, once a source of mutual benefit, are fraying, with trade disruptions and rising protectionism on both sides. Most dangerously, the risk of border incidents or even insurgent resurgence in India’s northeast is growing.

To arrest this downward spiral, India must first look inward. At this critical juncture, the question is no longer whether geography makes India vulnerable, but whether its own choices have become a dangerous liability.

Rather than blaming external actors for Bangladesh exercising its autonomy, India must recommit to democratic values. Only then can New Delhi rebuild trust with the Bangladeshi people. The Modi government must work toward curbing Islamophobic rhetoric within its ranks. It can’t allow its Hindu-majoritarian domestic politics to dictate India’s foreign policy. The language of exclusion and suspicion must give way to respect and partnership.

The Modi government’s attempts to employ a punitive strategy have failed in South Asia, whether in Nepal, the Maldives, or Bangladesh. Rather than economic coercion, India should offer positive incentives: trade, investment, and connectivity projects that benefit both sides. It is high time that India recognizes that its neighbors have agency. Building coalitions, not dependencies, is the only sustainable path to regional stability.

The current situation is about more than the Siliguri Corridor or maritime access to the Bay of Bengal. It is a test of whether India can adapt to a multipolar South Asia, where smaller states want to reassert their sovereignty. If the Modi government fails to recalibrate, it risks not only the loss of Indian influence in Bangladesh, but also the unraveling of its entire Neighborhood First and Act East policies.

The lesson is clear: Strategic depth cannot be bought with autocratic bargains or defended with force alone. It must be earned through respect, restraint, and a willingness to see neighbors as equals.

Sushant Singh is a lecturer at Yale University and a consulting editor with India’s Caravan magazine. He was previously the deputy editor of the Indian Express and served in the Indian Army for two decades. X: @SushantSin

More from Foreign Policy

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.