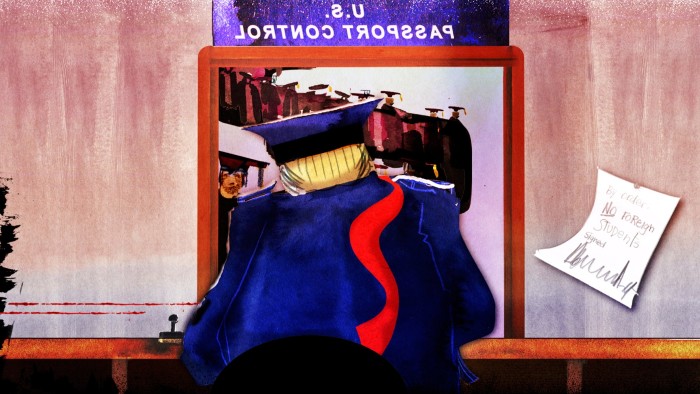

Trump’s attack on Harvard won’t make America great again

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

The writer is a professor at Harvard University and former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers

I believe in staying in my lane and limiting myself to economic arguments and analysis where I have some expertise or at least comparative advantage. There is much to say about the economic madness of the Trump administration’s attempt to in effect expel more than 6,500 Harvard students — about one-quarter of our student body. But the real reason I’m so shocked, saddened, outraged and bewildered is personal.

During my sophomore year at Harvard, I lived with two of my closest friends, a Canadian and a South African. Through them and many other international friends, I encountered new ideas, fresh perspectives — and simply had fun. Some stayed in the US and became doctors, academics, journalists, and businesspeople. Others returned home but carried with them a lasting connection to the country and all it has to offer.

After graduation, the tables turned, and I was a foreign student myself at the London School of Economics. I didn’t stay in the UK — though my tuition payments did — but I felt strongly about our own special relationship. When the UK government asked me years later to chair a panel to help them revamp digital competition policy, that goodwill returned, and I jumped at the chance.

I returned to do a PhD in economics at Harvard. Most of my cohort were foreign nationals in the US on visas. Harvard thinks of itself as American and primarily accepts Americans — only around 15 per cent of undergraduate students are foreign. When it comes to the PhD programme, however, Harvard seeks the most outstanding potential scholars from wherever they live — and it’s no surprise that with almost 96 per cent of the world’s population outside the US, many come from abroad.

Most of my international classmates stayed and are now working in top US research departments. Others went on to other leading universities around the world, governments and international organisations. The global connections I had made benefited me — and the US — when I served in President Barack Obama’s White House. Knowing people in the French treasury and Bank of England was useful during the Eurozone crisis and Brexit.

Now I’m back at Harvard teaching. One of my students is from a village in India whose family had never flown in an aircraft before she left. Another came from a small Italian town that had never sent anyone to an American university. Others are refugees from war-torn countries. Last month, at a faculty lunch with a group of economics undergraduates, half of the students who showed up were international. Many will return home after graduation, where they will apply what they have learnt. Others stay and contribute here.

So, when I think about what the Trump administration is doing, I think of these hundreds of friends, students, and colleagues. But even if I set those feelings aside, the economic cost is enormous. The US is the world leader in higher education. Degree-granting institutions employ 4 million people, from janitors and support staff to administrators and faculty. The US receives as much as $50bn annually from 1mn foreign students — which counts as an export.

Many foreign students don’t just pay while they are here; they stay and add to our labour force, increasing productivity and becoming innovators, founders and intellectual leaders. Without international students and immigrants we might have never head Indra Nooyi as CEO of PepsiCo, Jensen Huang who co-founded Nvidia, or Satya Nadella and Sundar Pichai as CEOs of Microsoft and Google — or even Elon Musk.

America’s strength has never come from drawing solely on the talents of the small percentage of the world’s inhabitants who live here — but from attracting the best from anywhere. The breakthroughs we take for granted — from modern medicine to the internet — are often traced back to global collaborations at universities, including Harvard.

I hope that the courts show it to be unlawful to make arbitrary sweeping changes based on a bad faith claim about antisemitism to undertake a punishment that is not supported by any Jewish faculty or students I know, including myself.

I am a big fan of openness to trade and capital flows. However, openness to ideas and people is even more critical. And Harvard, like other universities, is the epitome of that openness. No wonder President Trump is targeting us. For the sake of America and the world, these drastic actions must be stopped.