You Need Allies to Win a Trade War

You Need Allies to Win a Trade War

Trump could have cornered China—instead, it’s the biggest winner of his attack on global trade.

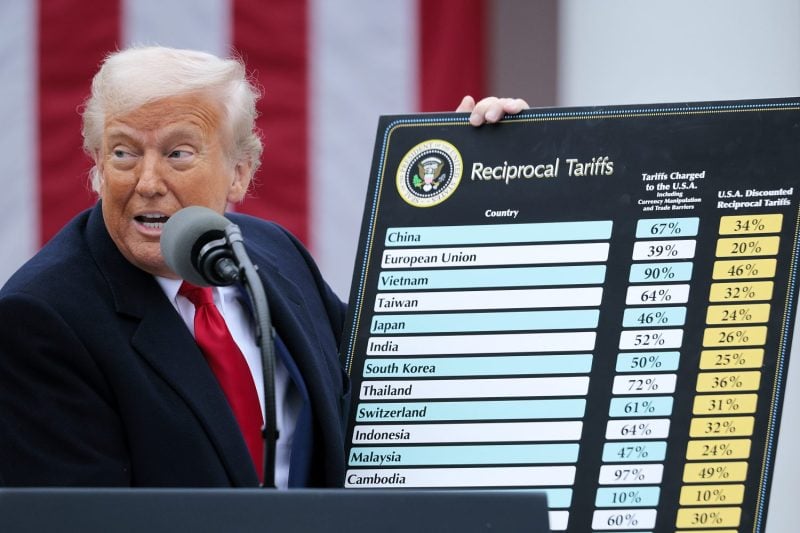

U.S. President Donald Trump holds up a chart showing foreign tariff rates, later shown to be false, and new U.S. rates during an event in the Rose Garden at the White House in Washington on April 2. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Financial markets and U.S. businesses relying on imports have forced U.S. President Donald Trump to significantly climb down from his recent tariff broadside against most of the world but especially Western allies and China. However, he could have extracted more concessions from Beijing if he had pursued a strategy of all against one, rather than one against all.

The United States may account for more than half of global stock market capitalization and roughly a quarter of world GDP, but it only produces 9 percent of global good exports and takes in 14 percent of global goods imports. No single country—not even the United States—is a unipolar superpower when it comes to trade in goods, which is where Trump wants to fight his war. A coalition of countries could have more seriously challenged China, but collective action now looks impossible, given the extent to which Trump has alienated Washington’s traditional allies.

Financial markets and U.S. businesses relying on imports have forced U.S. President Donald Trump to significantly climb down from his recent tariff broadside against most of the world but especially Western allies and China. However, he could have extracted more concessions from Beijing if he had pursued a strategy of all against one, rather than one against all.

The United States may account for more than half of global stock market capitalization and roughly a quarter of world GDP, but it only produces 9 percent of global good exports and takes in 14 percent of global goods imports. No single country—not even the United States—is a unipolar superpower when it comes to trade in goods, which is where Trump wants to fight his war. A coalition of countries could have more seriously challenged China, but collective action now looks impossible, given the extent to which Trump has alienated Washington’s traditional allies.

In 2023, China exported $449 billion in goods to the United States, while it imported only $144 billion in the reverse direction. Given this difference, the same tariff rate would have raised three times more money in the United States than China. Perhaps for this reason, Trump assumed that tariffs would be a lot more painful to China than to the United States. When China raised tariffs on U.S. imports in response to Trump’s trade broadside, he suggested that Chinese President Xi Jinping “panicked” and that the Chinese economy “cannot afford” such a policy.

But a tariff is a tax on a transaction that involves an importer and an exporter. The importer pays the tax, but who ultimately absorbs the extra cost depends on what options each side of the transaction has. Importers are weak if they have few alternative options to source the goods; they would have to absorb the cost of the tariff and pass as much of it as they could to the importing country’s consumers. Exporters are weak when they have few alternative markets for their products, so they would have to lower their prices and absorb the tariff that way.

What matters is each side’s ability to find alternatives to the transaction that is being taxed. The United States would be strong if it exported many products on which China depended yet it did not depend that much on the Chinese market. In this situation, there would be no strategic value for China to impose tariffs, as it would experience significant pain while U.S. exporters could sell their products elsewhere.

We used bilateral trade data covering more than 1,200 product categories to check how extensive the list of products is for which the United States is in a strong position, meaning that (1) a majority of Chinese imports in that category came from the United States, (2) a minority of U.S. exports in the category went to China, and (3) the U.S. export value to China was significant, exceeding $500 million. We found only four product categories that met the criteria, and they were not the most sophisticated: animal feed, miscellaneous nuts, miscellaneous cellulose, and agricultural machinery. Altogether, these exports to China were worth just $2.2 billion in 2023.

The equivalent list of exports that could exert significant pressure on China runs to three categories each for Germany, Japan, and South Korea; four for New Zealand (all agricultural); and one each for France and Australia. Together, these add up to just over $20 billion in export value. Other countries, such as Britain and Canada, have no such products.

Beyond these product categories, there are narrower technological categories for which Washington has attempted to restrict Beijing’s access to Western goods, including the high-end semiconductor chips (and the equipment to manufacture them) that are critical for artificial intelligence applications. China has in part managed to circumvent this restriction by using foreign data centers, developing its own advanced chips, and making machine learning more efficient and thus requiring fewer hardware resources, as evidenced by DeepSeek’s breakthrough AI model.

From this perspective, China’s strategic trade situation could not be more different. The same calculation for Chinese exports to the United States yields 49 product categories worth $88 billion in total, including household appliances, household utensils, mattresses and bedding, sports equipment, toys, and games. In these markets, Trump would inevitably face greater pressure for tariff relief from U.S. importers than from Chinese officials. And that is exactly what happened.

What these numbers make clear is that a unified Western effort could have been much more effective. When we pool the United States together with the European Union, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea, the list of products on which China depends grows to 181, worth $396 billion. Each individual country may account for just a fraction of exports, but together they represent a huge portion of the world’s advanced industrial output. These products include a variety of industrial machinery and instrumentation, auto and aircraft parts, and chemical compounds that China’s manufacturing juggernaut vitally depends on. Rather than launching a general tariff war, Western allies could have imposed an embargo on these goods to threaten the Chinese economy.

It can’t be said often enough that the system of Western economic, military, and diplomatic alliances, carefully cultivated by the United States over many decades, has long been a source of strength in times of crisis. Trump was elected twice in part because he was among the first politicians to treat the impact of Chinese trade on American workers as a crisis. In an alternate universe, he may have drawn on the West’s vast collective power to materially change Chinese trade behavior.

Of course, Trump has never really articulated what he actually wants from his trade war. Laudable goals might include halting Chinese intellectual property theft, limiting subsidized dumping practices, and granting more equitable access to Chinese consumer markets. Other Western countries frequently complain about these problems, and Trump would likely have found many sympathetic ears.

To be sure, coordinated trade pressure from Western allies in the past has typically been exerted on countries that are far from essential to global value chains, such as South Africa during apartheid, Iran due to its nuclear ambitions, and Russia following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. China’s magnetic pull toward Western businesses due to its economic heft poses a major hurdle toward unified trade action or other pressure. For example, Volkswagen was notoriously slow to address the ethical implications of operating a joint venture in Xinjiang, where the Chinese state heavily persecutes Uyghurs, including through forced labor. Sufficiently cajoling the Western world into action could realistically only have come from a highly motivated U.S. president.

But Trump squandered this possibility outright by launching an offensive against U.S. allies. Nearly 60 percent of Canadians, for instance, are now actively boycotting imported U.S. products in response to the trade war and Trump’s threats to annex their country. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney has declared that the long-standing relationship with the United States “is over,” and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen affirmed that “the West as we knew it no longer exists.”

Moreover, other Western countries are less likely to put pressure on China through trade action when their access to the U.S. market has just been curtailed. On the contrary, they may see an opportunity to eat away at U.S. market share in China to make up the ground they are losing in the United States. For example, China imported $9.6 billion in medical instruments in 2023. Of this total, 37 percent came from the United States, but 15 percent came from Germany, 12 percent from Japan, and 5 percent from the Netherlands. Companies in the latter countries may enjoy a surge in orders if Beijing’s tariffs on U.S. imports hand them a price advantage.

China is thus arguably the biggest geopolitical winner of Trump’s trade wars. Whereas an invasion of Taiwan may previously have entailed paralyzing trade sanctions by a united Western alliance, China now faces a disunited West. Western cohesion will get further eroded as China deepens its economic ties with Western countries now spurned by the United States. If Trump’s goal was to bolster China’s global standing, it is hard to see how he could have been more effective.

This post is part of FP’s ongoing coverage of the Trump administration. Follow along here.

Ricardo Hausmann is the founder and director of Harvard University’s Growth Lab, a professor of practice in international political economy at Harvard Kennedy School, a former chief economist at the Inter-American Development Bank, and a former Venezuelan minister of planning.

Eric Protzer is a senior research fellow at Harvard University’s Growth Lab and a co-author of Reclaiming Populism: How Economic Fairness Can Win Back Disenchanted Voters.

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.