‘Expect no miracle’: Ukraine braces for Russia’s summer offensive

Donald Trump’s threat to withdraw US support and walk away from Russia-Ukraine peace talks has raised alarm in Kyiv, setting the stage for what Ukrainian officials and soldiers expect to turn into a bloody Russian summer offensive that could reshape the war’s trajectory.

While Ukraine’s leaders continue their push for a 30-day ceasefire, many people are under no illusion about Russia’s years-long war winding down any time soon, Ukrainian officials and soldiers have told the Financial Times.

They argue that Russia shows no sign of scaling back its military assaults or making real concessions. A recent meeting in Turkey, they said, left Kyiv’s negotiators convinced that peace remains a distant prospect.

There, Russia’s lead negotiator warned they could again invade and capture Ukraine’s northern Sumy and Kharkiv regions, according to a Ukrainian official. Days later, on a visit to Russia’s Kursk region where Ukrainian forces have been pushed out, President Vladimir Putin joked approvingly when a local official said neighbouring Sumy “should be ours”.

On Thursday, Putin announced that his forces were “creating a security buffer zone” along the Ukrainian border, a term that has been used before to signal cross-border incursions.

Washington’s oscillating support for Kyiv has only emboldened the Russian leader. After speaking at length with Putin on Monday, the US president informed Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy that the two sides should settle the terms of a peace deal among themselves.

European governments, too, have been slow to act on pledges to bolster security, including a proposed “reassurance force” that has yet to materialise and some in Kyiv worry may never come to fruition.

Yehor Firsov, an MP and drone unit commander in Ukraine’s 109th Brigade, said it’s time his country faces the “harsh reality” that Russia’s confidence may outlast western unity.

“Putin is convinced he can break Ukraine,” he said. “He simply believes our complete capitulation is only a matter of time . . . the US might stop its aid any day now. He sees Europe as weak and indecisive.”

Along Ukraine’s more than 1,000-kilometre frontline, the rhythm of war has settled into a brutal, deadly pattern. Moscow is regrouping ahead of what soldiers and analysts said is the lead-up to a new, big push in the months ahead.

Ukrainian troops on the eastern front said that Russian infantry are darting around on motorcycles, buggies and electric scooters. Said Ismahilov, a soldier who was once Ukraine’s senior Muslim cleric, compared them to a “swarm of locusts . . . not one great wave, but an endless stream.

“They don’t care about losses. They just keep coming . . . not to take kilometres, but metres — wrecked trenches, a few blasted trees, the shell of a house.”

Fighting has intensified in recent weeks around Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka, pressuring the strongholds of Kramatorsk and Slovyansk and approaching the borders of neighbouring Dnipropetrovsk region.

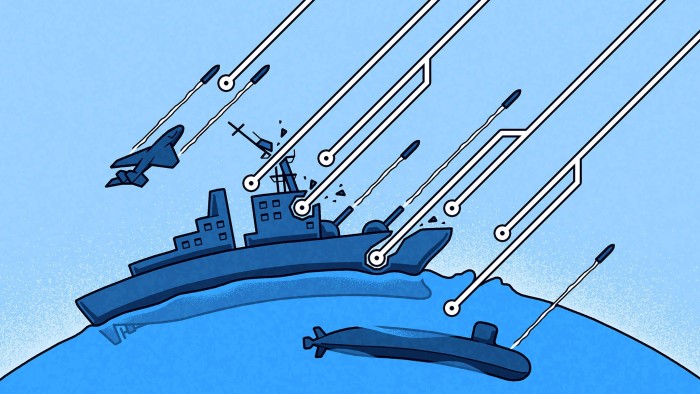

Aiding the infantry is Russia’s heavy and high-tech weaponry blasting its way through, with glide bombs, missiles and drones — including new models connected via fibre-optic cables that make them immune to electronic jamming. Defenders have been forced to pull back from towns including Toretsk and Chasiv Yar, where the cost of holding ground proved too high.

However, the Ukrainians “remain a formidable force on the defence”, said Franz-Stefan Gady, a Vienna-based military analyst. “We can expect gradual Russian advances but no imminent collapses, no collapse of the front line.”

The Ukrainians are now much less dependent on the US for artillery supplies, with the Europeans having stepped up. Russia has only “slight superiority in artillery fire,” he added.

A deputy commander of an assault unit near Pokrovsk said they were still holding the line, “but we’re exhausted”. He has fought since 2014, through injuries, and missing family milestones. Trump’s campaign pledge to end the war in “24h” initially gave him a glimmer of hope. But recent developments have forced him and his troops to ignore the news because it sends them into a rage.

“It’s just noise. Propaganda. Lies,” he said. The war has narrowed his world to “the next mission . . . the next fight” — so much so that at times he doesn’t feel human. “I’m a zombie.”

That sense of exhaustion and frustration is spreading through the ranks. Among both seasoned officers and newly mobilised troops, morale is fraying — worn down by a growing feeling that there is no clear plan to end the war, and that lives are being sacrificed for nothing.

Oleksandr Shyrshyn, a battalion commander in the elite 47th Mechanised Brigade, went public this week with his concerns. His unit operates US-made Abrams and German Leopard tanks — symbols of Kyiv’s western backing — but he wrote on social media that even the best equipment cannot compensate for flawed planning that sent his men into harm’s way.

“In recent months, it has started to feel like we are being erased — like our lives are being treated as disposable.

“The problems are systemic, not personal,” he added, urging a sober reassessment of operational capacity and a strategy that matches the battlefield reality.

Ukraine’s General Staff responded to his complaint by saying it was looking into the matter.

The war has exposed long-standing weaknesses in Ukraine’s command structure. Fixing them is difficult “when you’re engaged in the highest-intensity war since the second world war,” said Konrad Muzyka, director of the defence consultancy Rochan.

Some reforms are under way, but doubts linger about whether they will go far, or fast, enough to meet the moment.

Manpower remains one of the most pressing issues.

At a Kremlin meeting on economic development this month, Putin claimed that up to 60,000 Russians “volunteer” to join the army each month — double the roughly 30,000 Ukrainians he said were being conscripted. Some analysts believe both figures to be slightly inflated.

However, Ukraine has refused to lower its conscription age below 25, resisting pressure from the US and other allies. Its mobilisation drive remains riddled with corruption and forced conscription, including recruitment officers nabbing unregistered men off the street and stuffing them into vans. A recruitment drive to attract 18 to 24-year-olds has largely failed, with only several hundred applicants, according to people briefed on the programme.

A rare bright spot for Ukraine remains its domestic drone production, able to inflict serious damage and stall some of the Russian advance.

Ukraine’s military is also borrowing from video game culture to incentivise its drone units. An initiative launched in April rewards troops with digital points when they submit verified footage of Russian targets destroyed by their drones. The points can be used to buy drone parts and equipment on a dedicated platform, the “Brave 1 Market”.

Still, Valery Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s former top general and current ambassador to the UK, warned a London audience on Thursday not to expect “some kind of miracle . . . that will bring peace to Ukraine”.

“With an enormous shortage of human resources and the catastrophic economic situation we’re facing — we can only talk about a high-tech war of survival,” he said. The priority for Ukraine was to fight in a way that “uses minimal human resources and minimal economic means to achieve maximum effect”, he said.

Russian missile strikes hitting civilian areas in Ukrainian cities well beyond the frontline remain a serious concern. Muzyka’s team has tracked major attacks across this spring — some involving more than 200 missiles each. Russia is now producing more rockets than it launches, while Ukraine’s Patriot interceptors are running low.

Drone attacks are also intensifying. Russia launched over 2,000 Iranian Shahed drones in the first 20 days of May alone. While Kyiv has improved its capacity to distinguish between decoys and those with live warheads, the sheer number is becoming unmanageable.

“More will get through and hit their targets,” Muzyka said. Russian drones have also been upgraded and now fly higher and faster, making them harder to shoot down with machine guns. Patriot systems and F-16s — both in short supply — are often the only viable counters.

Ukraine lost one of its F-16s in mid-May during an air mission, with the pilot ejecting after downing three targets.

Many soldiers and, increasingly, officials say the country must brace for a long, asymmetric struggle.

“How long will it last?” Firsov asked. “Until we break the Russians’ belief that we can be defeated.”