Congress Takes Aim at a Pillar of Civil Society

Congress Takes Aim at a Pillar of Civil Society

Provisions in Trump’s tax package are the latest in a global crackdown on nonprofits.

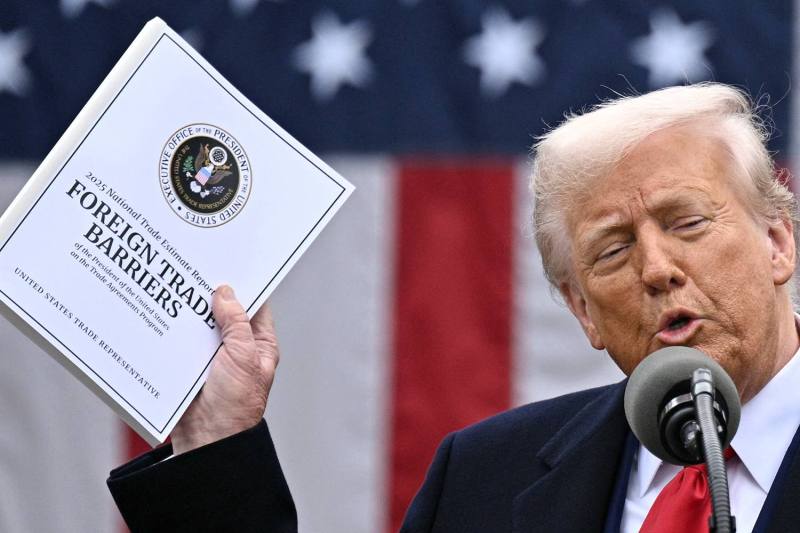

U.S. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson (R-LA) speaks to the media after the House narrowly passed a bill forwarding President Donald Trump’s agenda at the U.S. Capitol in Washington on May 22. Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

On Nov. 21, 2024, the U.S. House of Representatives greenlit HR 9495, known as the Stop Terror-Financing and Tax Penalties on American Hostages Act. The bill postpones tax filing obligations for Americans who have been wrongfully detained or held hostage abroad. But, disturbingly, the bill also empowers the Treasury secretary to designate any nonprofit as a “terrorist-supporting organization” and revoke its tax-exempt status. Its provisions are now a part of the new Republican tax package that has now passed the House and is headed to the Senate.

Organizations including Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and Oxfam have condemned these provisions over concerns that they lack transparency and offer no protection against abuse. Critics argue the law would give authorities broad powers to harass and potentially silence a wide range of nonprofits, such as those focused on human rights, climate, and the environment, as well as news outlets and even service provision groups such as food pantries, churches, and domestic violence shelters.

On Nov. 21, 2024, the U.S. House of Representatives greenlit HR 9495, known as the Stop Terror-Financing and Tax Penalties on American Hostages Act. The bill postpones tax filing obligations for Americans who have been wrongfully detained or held hostage abroad. But, disturbingly, the bill also empowers the Treasury secretary to designate any nonprofit as a “terrorist-supporting organization” and revoke its tax-exempt status. Its provisions are now a part of the new Republican tax package that has now passed the House and is headed to the Senate.

Organizations including Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and Oxfam have condemned these provisions over concerns that they lack transparency and offer no protection against abuse. Critics argue the law would give authorities broad powers to harass and potentially silence a wide range of nonprofits, such as those focused on human rights, climate, and the environment, as well as news outlets and even service provision groups such as food pantries, churches, and domestic violence shelters.

The bill fits within a broader global trend of governments undertaking administrative crackdowns against civil society organizations. An administrative crackdown uses law to create barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). These laws often seem mundane and apolitical. And because they are framed as regulation rather than repression, political leaders are less likely to encounter domestic backlash in response to the their passage. But these seemingly innocuous legal maneuvers can have a chilling effect.

Under this bill, once the Treasury Department designates a nonprofit as a “terrorist supporting organization,” the group would have 90 days to respond and show that it did not provide material support or resources to terrorists. If its appeal is unsuccessful, the group would be stripped of its 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status. Importantly, the provisions do not require the Treasury secretary to share their evidence with the accused nonprofits.

Without such transparency, the ACLU argues that it would create a high risk of politicized and discriminatory enforcement. It would also run counter to constitutional due process protections by placing the burden of proof on accused organizations. To defend themselves, accused organizations will have to devote critical time, effort, and resources that could be better spent accomplishing their missions. Indeed, research on previous anti-terrorism laws shows that once a nonprofit is placed on a terrorism list, there is virtually no recourse to challenge that designation. Moreover, even if an organization is exonerated, it may deter potential partners, donors, and collaborators—as has already been the case with the Trump administration’s attacks on civil society institutions.

Proponents of the bill champion it as a strategy to strengthen the government’s fight against the financing of terrorism and extremism, arguing that terrorism financing “should not have preferential treatment under the U.S. tax code.” An earlier version of the bill was introduced in 2024 amid widespread protests across university campuses over Israel’s war in Gaza, with the suggestion that at least some of the groups organizing these protests could be supporting terrorism. More recently, the Trump administration threatened to revoke Harvard University’s tax-exempt status as a nonprofit, arguing that it should be taxed as a political entity, after the institution rebuffed U.S. President Donald Trump’s efforts to control the university administration and its hiring practices.

But the United States already wields extensive tools in the fight against terrorism. It has some of the strictest counterterrorism NGO regulations in the world. It is already illegal under U.S. law to provide material support for terrorism. Under the Bush administration, Executive Order 13224 created a list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists, froze their assets, and banned all transactions with them. It also gave the Treasury broad powers to target the financial infrastructure of global terror networks. The Patriot Act increased criminal penalties for intentionally providing material support or resources for terrorism.

These counterterrorism regulations also affected policy globally. Following 9/11, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental organization, recommended standards for governments to pass laws to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing. One of the FATF recommendations specifically pertained to enacting regulation that prevents nonprofits from serving as fronts for money laundering or financing terrorism. FATF recommendations also flagged that countries should identify a subset of nonprofits that are vulnerable to terrorist financing abuse. Countries should apply proportional measures to a subset of nonprofits in light of a risk-based approach. The FATF repeatedly rejected the notion of national measures—such as those in the bill—that treat all nonprofits in the same manner.

Many countries have not taken this recommendation when passing nonprofit laws. The U.N. Special Rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights has highlighted how such overly broad laws on nonprofits and terrorism have been used to target a wide range of civil society actors and “criminalize peaceful activity in defense of minority, religious, labor, and political rights.” For instance, in Turkey, a law on the financing of terrorism allows the state to seize a nonprofit’s property without a judge’s ruling if it is deemed as having terror assets. In Sri Lanka, a similar law gives authorities broad discretion to seize a nonprofit’s property without a prior court order.

Such restrictive NGO laws have had devastating consequences for many nonprofits. This is especially the case for humanitarian and aid organizations that have to work in environments where even the smallest circumstantial evidence could be grounds for designation. HR 9495 could potentially paralyze aid operations in conflict settings where actors deemed “terrorists” control large swathes of territory, forcing humanitarian and peacebuilding organizations to pay fees for permits or have their operations taxed. For instance, after the United States listed al-Shabaab in Somalia as a terrorist group, it resulted in a 88 percent reduction in aid to Somalia over the next two years, with devastating consequences for its people.

These laws can also have a chilling effect as nonprofits may engage in self-censorship. In Turkey, because of the Anti-Terror Law, nonprofits face a huge penalty if terrorist propaganda is suspected to have been spread within their physical premises. In Bangladesh, after the passage of numerous restrictive laws including the Money Laundering Prevention Act and the Anti-Terrorism Act, NGOs with a broad mission ended up restricting themselves to service work and giving up on their advocacy work. In Egypt, a law criminalizing nonprofit activities led to the retreat of international rights organizations like Human Rights Watch from the country, and local rights organizations outside the capital city of Cairo shut down their offices.

Similar laws have also affected the work of service provision or developmental groups, including where local government authorities use anti-nonprofit rhetoric.

Crackdowns deter donors, who may increasingly prefer less risky programming. Research shows that donors committed to political advocacy and democracy promotion reduced funding for advocacy programs by more than 70 percent in response to new restrictive NGO laws, and the reduction in aid has persisted for several years. To maintain access to target countries with restrictive laws, donors have increasingly tamed their programming by avoiding contentious issues such as human rights, media freedom, and anti-corruption, instead focusing on causes such as health and education.

As a result, local NGOs may become strapped for money. Even local philanthropists may be deterred from donating to advocacy, media freedom, and anti-corruption initiatives due to a fear of retribution. Philanthropy by ordinary people is unlikely to replace the scale of state or foundation funding that sustains many nonprofits.

On a broader level, these restrictive laws can worsen the repression of human rights. Administrative crackdowns on NGOs can provide convenient avenues for greater levels of societal repression and government transgressions. Recent research shows that the implementation of these laws predicts state authorities’ worsening respect for physical integrity rights and civil liberties. Targeting these nonprofits may set the groundwork for future democratic erosion.

Laws regulating nonprofit behavior should be grounded in international and domestic legal principles that give civil society groups the right to freedom of association and the ability to access necessary human, material, and financial resources. Before enacting further legislation when laws restricting material support for terrorism already exist, U.S. officials should seek input from international human rights bodies, which have greater expertise in evaluating the human rights implications of counterterrorism legislation. Otherwise, it risks adding to the disturbing body of global laws that allow governments to maintain an illusion of democracy and civic pluralism as they create new ways to control opposing voices.

Suparna Chaudhry is an assistant professor of international affairs at Lewis and Clark College.

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.