How Wall Street offloaded $13bn of debt tied to Musk’s Twitter deal

Elon Musk promised his bankers they would not lose money on the $13bn they lent to finance his Twitter takeover in 2022. The world’s richest man has now largely made good on his vow after Donald Trump’s re-election helped rescue the debt deal.

The sale by seven banks last month of the final slug of loans for Musk’s $44bn Twitter buyout marked an extraordinary turnaround for debt that had once appeared to be toxic. The lenders including Morgan Stanley and Bank of America faced a stark choice: offload the loans at a steep discount and lock in big losses, or trust guarantees Musk made in private.

Their decision to hold the debt began to pay off in November, after Trump won the US election. Musk, one of the president’s closest allies, became a fixture in the White House — a shift that has elevated his influence and rippled across his business empire.

As bankers offloaded the final vestiges of the debt financing at the end of April, X took the unusual step of covering some losses that banks would usually absorb, people with knowledge of the matter said.

While the $1.2bn of loans were priced with a small discount, at 98 cents on the dollar, X made up the difference, the people said.

“I could do cartwheels,” one banker involved in the deal said. “It was a bet on the world’s richest man, and it paid off,” a second person said.

—

This account is based on more than a dozen interviews of people familiar with the financing of Musk’s Twitter purchase, which marked one of the most difficult debt deals for Wall Street since the 2008 financial crisis.

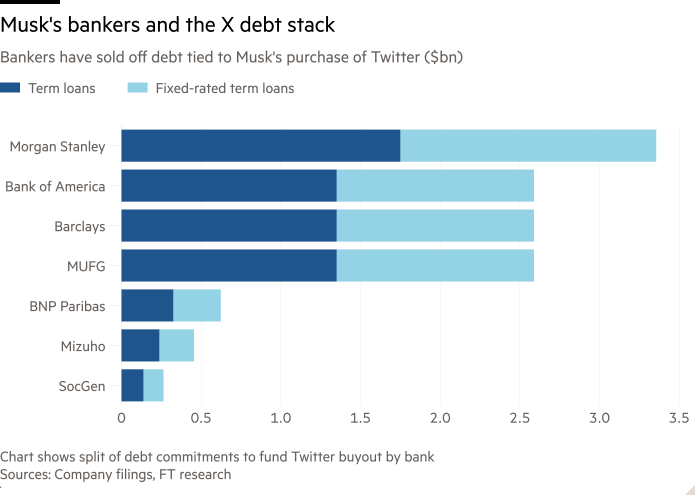

Morgan Stanley had rallied six other banks as it raced to provide financing to Musk in April 2022, with lenders tripping over each other to cement their ties with the billionaire.

The cohort, which included Bank of America, Barclays and MUFG, had just days to conduct due diligence and sign up to the deal as Musk pushed forward with his hostile takeover.

But just weeks later, with Musk attempting to back out of the buyout, it became apparent that they would have to provide roughly $12.7bn of loans themselves instead of selling the debt to large investors. They were “hung”, in Wall Street parlance.

As X’s business deteriorated, the banks were left holding billions of dollars of loans that were sinking in value. Federal Reserve rate rises in 2022 only made matters worse — as the banks had agreed to cap the interest rate on the debt they extended to X.

Investors, sensing the despair at the seven banks, began bidding on the debt. In 2023, some offered just 60 cents on the dollar, which would have implied losses of more than $4bn.

Morgan Stanley held the lenders together, betting on the relationship of one of its then top bankers — Michael Grimes — and his client Musk, people familiar with the matter said. The bank led weekly calls to update the other lenders on X’s performance. Working together as a bloc helped avoid one single bank abruptly selling the debt at a discount.

“The banks knew if someone dumped a portion at 50 cents on the dollar they’d all have to take a massive hit,” one debt investor who did due diligence on the loans said.

Everything changed on election night 2024, which featured scenes of Musk side-by-side with a victorious Trump. The banks spotted their exit and Morgan Stanley finally began leading serious conversations with investors. Bids that were just 70 cents on the dollar before the election had shot up 75 to 80 cents on the dollar.

Morgan Stanley declined to comment, while X did not respond to requests for comment.

The importance X played in the election was not lost on the bankers and a rally in debt markets was only helping their book. Musk’s decision to give X a stake in his fast-growing artificial intelligence company xAI also burnished the social media company’s prospects.

“He’ll never let Twitter [X] fail,” a banker involved in the deal said. “I don’t think people even did their credit work. They just trusted the Musk halo.”

In January, the banks quietly sold the first chunk of debt they had been holding for years to two investors, Diameter Capital Partners and Darsana Capital Partners. The firms bought $1bn of the loan at 93 cents on the dollar, according to three people familiar with transactions.

The sales to Diameter and Darsana helped “build interest” from other investors, one person who bought the debt said of Diameter’s role.

Bankers were enthusiastic with the result — and began contacting the world’s largest credit shops. Before they would share any of X’s financial information and performance, they wanted to know that an investor could buy $250mn or more of the debt.

Some investors who looked at the debt were aghast with the information they were given. Financials were heavily adjusted and while the company’s revenues looked to have bottomed, the data on offer lacked many of the key figures most investors would need to conduct due diligence. Several told the Financial Times the business had shed cash at a rapid rate.

But buyers including Apollo Global and Citadel lined up and Morgan Stanley successfully sold $5.5bn of term loans in early February, this time at 97 cents on the dollar. The price was important. Banks generally break-even on their underwritten debt deals at 96 or 97 cents on the dollar, as the fees they earn offset the discounts provided to entice buyers.

“They were able to sell it off some of the thinnest financials,” one investor who passed on the deal said. “It was surprising, you could do it as a trader — but to buy $1bn, which they want us to do, we don’t do that . . . It was fucking wild.”

“Twitter was not an investment, it was a trade,” a second investor who bought some of the loans said. The person added it was “too early to know if they’re through the trough”.

Just days later the banks returned and sold another $4.74bn of fixed-rate term loans at par — or 100 cents on the dollar — earning their fees on that portion of the sale. Demand was so strong that the size of the sale was increased, leaving the banks with roughly $1.2bn junior loans — the riskiest part of the financing — they had agreed to provide.

In April, the banking cohort sold the final $1.2bn of debt, winning a reprieve from lenders to convert those junior loans into more senior debt, slashing the company’s interest costs in the process.

Morgan Stanley’s first-quarter earnings were bolstered by the debt sales, with the US lender reporting nearly $700mn of “other” revenues within its investment bank, up from $242mn a year earlier. A person familiar with the matter told the FT that much of the boost was related to selling X debt. The bank had previously taken mark-to-market losses on the loan.

“Our investment thesis was correct,” a banker involved in the deal said. “We backed Musk more than we were backing Twitter itself.”

Still, another banker complained that the offloading of the hung loans was not reflected in their compensation.

“We made fees. We wrote the loan back up. But we didn’t see that reflected in bonuses,” one banker said. But they acknowledged: “You can’t ring the bell on something you had to hold for two years.”