Britain’s bank bailouts: an epic saga without a happy ending

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

After nearly 17 years, the UK government has finally sold its last shares in NatWest, formerly known as Royal Bank of Scotland. It marks the end of the most visible and enduring legacy of the 2008 financial crisis in British banking.

But as HM Treasury quietly exits stage left — with an estimated £10bn loss — it’s worth asking: what did this intervention achieve? And how did it compare to the approach taken across the Atlantic?

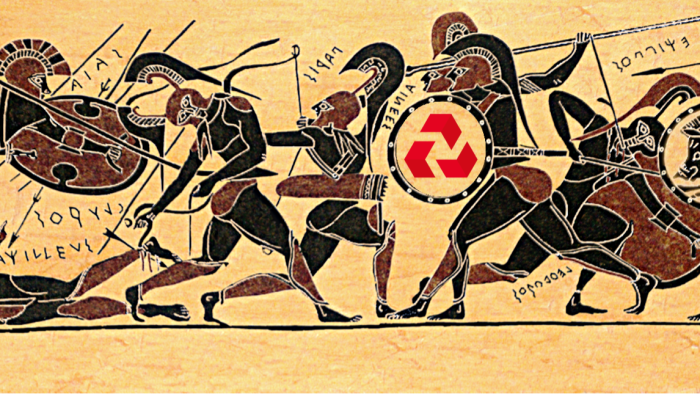

Both the US and UK faced the same urgent question in 2008: how do you shore up a collapsing financial system? In ways that echoed the two very different protagonists from Homer’s epics, Iliad and Odyssey, they arrived at very different answers.

In Homer’s telling, Odysseus is pragmatic and diplomatic, willing to compromise for the greater good and move past grievances, while Achilles is fiercely principled, even when it costs him and his community dearly. Where Odysseus sees strategy and necessity, Achilles sees betrayal and hypocrisy, making him wrathful. At one point in the Iliad, Odysseus tries to persuade Achilles to return to battle, offering lavish gifts from Agamemnon. Achilles, however, angrily rebuffs him, declaring, “I hate like the gates of Hades / the man who says one thing and hides another inside him.” This moment underscores Achilles’ fiery disdain for hypocrisy or double-dealing.

In responding to the financial crisis, the US adopted an Odyssean approach: tactically clever, limited in ambition, and focused on the endgame. Under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the US Treasury injected over $300bn into more than 700 financial institutions, mostly through preferred shares and warrants. These allowed the government to share in any upside but conferred no voting rights, except in limited and exceptional circumstances. It was a stabilisation strategy, designed to restore confidence and disengage cleanly — not out of haste, but out of calculated restraint.

For the most part, it worked. The state recovered its money and by 2014 had exited most of its positions with a small overall profit. The US didn’t moralise; it triaged. The model proved politically palatable and financially tidy, and avoided dragging the government into the business of running the banks.

The UK approach was more Achilles than Odysseus — bold, idealistic, and driven by a sense of moral indignation. Instead of backstopping its banks, the British state took large stakes in them. RBS became majority state-owned. Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley were nationalised. Lloyds required significant government equity.

The state was stepping in not as a lender of last resort, but as a new controlling shareholder. It was a full-on intervention, based on the belief that a fundamentally broken model system needed judgment and a reckoning as well as support.

But like Achilles, the UK’s determination came with a cost, both immediate and, as it turns out, enduring. While the US quickly cycled capital in and out, the UK became enmeshed for over a decade. Although some positions — such as Lloyds — eventually turned modest profits, the £10bn loss on RBS/NatWest is a reminder that principle doesn’t always pay.

And the price wasn’t only financial. State control meant inheriting not just assets, but liabilities stretching far back into the past. One revealing example: the notorious €3bn IPO of Dutch ISP World Online in March 2000, managed by Goldman Sachs and ABN Amro. A decade later, a lawsuit over inadequate disclosures resulted in a €110mn compensation payout from the banks. By that point, ABN Amro’s investment banking operations had been absorbed into RBS, meaning that UK taxpayers ended up footing nearly half of the bill for due diligence failures on an Amsterdam stock exchange flotation in the dotcom bubble.

It was a minor hit in financial terms, but a perfect symbol of the risks assumed by a government that chose to own the past in order to shape the future. When you take control of a sprawling financial institution, the risks you bear aren’t limited to what’s on the balance sheet today. You also buy the litigation, the legacy screw-ups, and the skeletons rattling around in the data room.

This is the unglamorous truth of public ownership: you don’t just get to steer the ship; you also are expected to clean out the bilge. The US avoided entanglement, while the UK walked directly into it, believing the sacrifice was necessary. The decision to take direct stakes gave the British authorities more oversight and arguably more control, but it also exposed taxpayers to a level of operational, legal, and reputational risk that would have been unthinkable under the US model.

Some still argue that the UK was right and that only full control could force change in an institution like RBS. Critics of the US method say it patched over deeper problems, avoided hard reform, and allowed a rotten culture to survive. But Odysseus got home — eventually — by being adaptable. Achilles won glory, but at a steep cost to himself and to those around him.

Seventeen years later, NatWest is fully back in private hands. But the question lingers: which party handled the rescues better? The US approach had flaws, but it allowed for quicker disengagement and gave the taxpayer a shot at a return. The UK’s approach was heavier, more moralistic in tone, and more punitive in practice, and also entailed carrying the past sins of banks longer than anyone expected.

It comes down to which path you believe leads to redemption: the cunning of Odysseus or the honour-bound fury of Achilles. And how long you’re prepared to live with the consequences of either choice.