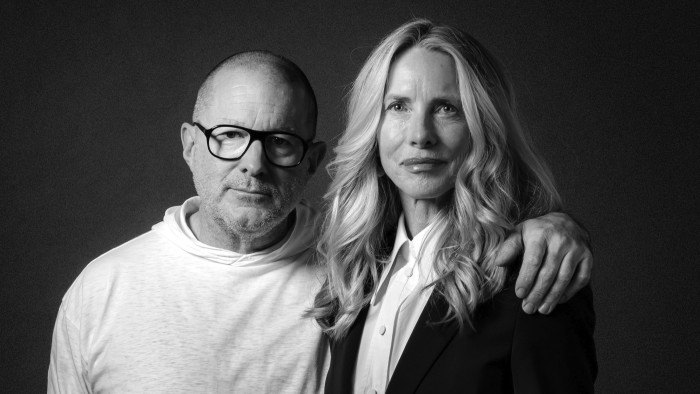

‘Humanity deserves better’: Jony Ive and Laurene Powell Jobs on tech’s next chapter

Sir Jony Ive remembers the day in 1997 when he first met Laurene Powell Jobs, outside the house she shared with her late husband, Steve. “I’m standing there, holding a model of the iMac,” he recalls, pointing to a picture on his office wall of the colourful computer, one of several images in a timeline of game-changing Apple products.

Steve Jobs had just returned to Apple after a decade away from the company he co-founded. The relationship he formed with Ive was critical to its subsequent soaring success. “I was often at the house,” Ive says. “Certainly on the weekends,” says Powell Jobs, sitting across from him on a long table. Ive nods. “It feels to me like we grew up together,” he says. “We’ve gone through hard things and happy things . . . ”

“ . . . family and children and work,” says Powell Jobs.

“There’s that Freud quote,” Ive says. “All there is, is work and love. Love and work.”

It is a maxim that guided the trio on those weekends and late nights at the house when Ive and Jobs were creating products such as the iPod and iPhone, which revolutionised personal technology and changed global human behaviour. And it has guided him and Powell Jobs since 2011 when Jobs died aged 56, their friendship enduring while taking on new work collaborations.

We are in the San Francisco offices of LoveFrom, Ive’s “creative collective”. The building, opposite an architectural bookshop beloved by Ive, has a nondescript exterior but inside is a minimalist’s dream with clean, sleek lines of construction that echo his own work. Even the office toilet has a slim digital control panel.

Powell Jobs, whose Emerson Collective owns The Atlantic magazine and has a philanthropy arm alongside investments in health, education and fintech companies, backed LoveFrom after Ive left Apple in 2019. “If it wasn’t for Laurene,” he says, “there wouldn’t be LoveFrom.”

She also invested in io, Ive’s AI design start-up, which was acquired by OpenAI last month in a deal worth $6.4bn. Announced via a video of Ive with OpenAI founder Sam Altman chatting about their collaboration in a nearby coffee shop, the deal was accompanied by the release of a black and white portrait of the pair, which some online wits compared to a similar shot of Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel. Terms of the deal have not been disclosed but it is known it will make Ive a billionaire, if he wasn’t already, at least on paper. Ive’s partners, including the designer Marc Newson, will also receive a windfall in OpenAI shares, as will Powell Jobs.

Ive and Altman have been tight-lipped about the AI-enabled device they are developing, and I wonder if it will invent a whole new category in the way the iPhone did for smartphones (speculation has swirled around some kind of screenless device). Ive deftly dodges my attempts to get him to tell me what it is but hints he was motivated by a disillusionment with how our relationship with devices has evolved. “Many of us would say we have an uneasy relationship with technology at the moment,” he says. I’m guessing this includes screen addiction and the harms caused by social media. Whatever the device is, driving its design is “a sense of: we deserve better. Humanity deserves better.”

He says the collaboration with Altman and OpenAI has revived his optimism in technology — optimism that has been dented by changes he has seen first hand in the home of the technology industry. “When I first moved here [in 1992] I came because it was characterised by people who genuinely saw that their purpose was in service to humanity, to inspire people and help people create. I don’t feel that way about this place right now.”

Powell Jobs agrees Silicon Valley has changed — and not necessarily for the better. “Thirty-five years ago we were still in the semiconductor era. There was the promise of making personal what had been available only to industry.” Apple played its part in that democratisation of technology, making beautiful, powerful computers for consumers. In recent years, however, there has been more public questioning of the role of Big Tech in our lives. She believes “people are still animated” by the idea that technology can be a force for good but adds a caveat. “We now know, unambiguously, that there are dark uses for certain types of technology. You can only look at the studies being done on teenage girls and on anxiety in young people, and the rise of mental health needs, to understand that we’ve gone sideways. Certainly, technology wasn’t designed to have that result. But that is the sideways result.”

Ive agrees. “If you make something new, if you innovate, there will be consequences unforeseen, and some will be wonderful and some will be harmful.” He acknowledges his own role in the products that have changed our relationship with technology. “While some of the less positive consequences were unintentional, I still feel responsibility. And the manifestation of that is a determination to try and be useful.”

AI continues to evolve and large language models are becoming more intuitive and powerful. Powell Jobs describes the current moment as “the era of the great unknown”. AI, she adds, will “transform how we live, work, relate, communicate. It’s not clear what direction the world is headed.”

If the io-OpenAI device has even a fraction of the impact of the iPhone it could, presumably, play a part in shaping how the AI era evolves. I wonder what her hope is for the collaboration. “My experience thus far with it is one of a trusted, beloved friend, but also [as an] admirer of new ideas.” She says she has watched “in real time how ideas go from a thought to some words, to some drawings, to some stories, and then to prototypes, and then a different type of prototype. And then something that you think: I can’t imagine that getting any better. Then seeing the next version, which is even better. Just watching something brand new be manifested, it’s a wondrous thing to behold.”

Surely this new device will compete with those made by Apple? She demurs. “I’m still very close to the leadership team in Apple. They’re really good people and I want them to succeed also.”

Powell Jobs, who is worth an estimated $15.6bn according to Forbes, worked in finance before meeting Jobs. A longtime friend and supporter of former vice-president Kamala Harris, she is an active philanthropist and started Emerson Collective in 2004, which she says “invests in entrepreneurs and innovators driven by purpose and a sense of possibility”. Press freedom and independent journalism are among the causes she has championed. “Freedom of the press is protected by the First Amendment, and until that’s changed, I will believe in it.”

I ask about “Signalgate”, The Atlantic’s recent scoop, when a member of the Trump administration mistakenly added the magazine’s editor, Jeffrey Goldberg, to a group chat on the Signal messaging platform about an imminent US strike in Yemen. “I’ll include you in a thread sometime,” Ive says. Great, I think: hopefully one where you spill the beans about the new AI device.

The Signalgate story prompted a furious response from the US president, who called Goldberg a “sleazebag” before inviting him in for an interview weeks later. “It’s very important to emphasise that, despite having the majority ownership stake in The Atlantic, I’m involved in the business side and not the editorial side,” Powell Jobs says. “We feel very strongly that freedom of the press means they are free to write the truth as they find it, and follow a story as they find it. It’s not up to us to approve or disapprove.”

One of her other passions — immigration reform, which would provide a path to citizenship for people brought to America illegally as children — is also in the spotlight. Powell Jobs refers to this cohort as the “Dreamers”: some estimates put their total number at more than 1mn. “They are the essence of America,” she says. “They are enormous contributors to society and to the economy.” Yet “they are at risk now”, as undocumented workers are targeted across the US. The Trump administration has not yet specifically gone after Dreamers, she adds, though if it did “I think it would be a grave injustice”.

It is time for the pair to have their picture taken, but not before Ive’s son Charlie, who works at LoveFrom, comes to say hello. We leave the office and walk a short distance up the block to a converted cinema, one of several properties Ive has bought and redeveloped in the area. San Francisco has suffered since the pandemic and many people have not returned to the city; he and Powell Jobs stayed and have continued to be based there. Powell Jobs was part of a non-profit group that recently bought the San Francisco Art Institute — and its vast Diego Rivera mural — out of bankruptcy. “We will ensure that it stays accessible to the public,” she says. “I feel I owe San Francisco,” Ive, adds. He was born in Chingford, south-east England, but has been a US citizen for more than a decade; San Francisco has been his home for more than 30 years. “I’ve benefited and have learnt so much from being lucky enough to live here.”

It’s clear there is an easy rapport between him and Powell Jobs but that shouldn’t be a surprise, given the length of their friendship. “It’s funny,” Ive says. “As I’ve got older, to me, it’s [about] who, not what. The very few precious relationships become so increasingly valuable, don’t they?”