Tusk reels as Poland’s ruling coalition braces for confidence vote

Donald Tusk’s ruling coalition has broken into fresh infighting after the Polish premier suffered a bruising defeat in the presidential race, stalling his reform plans and raising doubts over the government’s survival.

Tusk on Monday decided he would need to seek a vote of confidence in parliament to continue governing after the victory of the ultraconservative Karol Nawrocki left him facing another hostile president able to thwart his policy programme.

In a short address to the nation, Tusk said he had prepared a “contingency plan” to deal with Nawrocki and the influence of his right-wing nemesis, Jarosław Kaczyński.

But the victory for Kaczyński’s Law and Justice (PiS) party has already exposed deep fissures within Tusk’s unwieldy ruling coalition, which stretches from a conservative farmers’ party to greens and left-wing radicals.

With mounting speculation in Warsaw that the result will force early elections, Marek Sawicki, one conservative coalition partner, demanded that Tusk resign, saying: “If a horse doesn’t pull, you change it, instead of giving it a lighter cart”.

Magdalena Biejat, a leader of Tusk’s leftwing coalition partner, meanwhile argued Nawrocki’s election showed “the impact of the policy of half-measures and becoming similar to the far right”. While some of Tusk’s lawmakers have supported anti-abortion legislation introduced under PiS, others have pushed to legalise same-sex marriage as part of their progressive agenda.

Tusk’s centre-right allies from Poland 2050 called for the full renegotiation of the coalition agreement so they could enact “real change”. “I know these are bitter words, but it’s better to say it now than to cry in two years: more of the same thing brings more of the same,” said Katarzyna Pełczyńska-Nałęcz, a minister who represents Poland 2050.

Andrzej Bobiński, managing director of the think-tank Polityka Insight, said Tusk’s coalition faced “different scenarios that all look bad”. He argued Tusk was most likely to make “a sharp turn to the right” to reclaim ground from PiS and the far-right Confederation party, but said this risked alienating his more progressive partners and triggering a coalition break-up.

Recent opinion polls suggest that PiS could win snap parliamentary elections with support from the far-right Confederation. Kaczyński on Monday said Poland’s democracy had “shown its teeth” and called for Tusk to step aside to make way for a “non-partisan” government of technocrats.

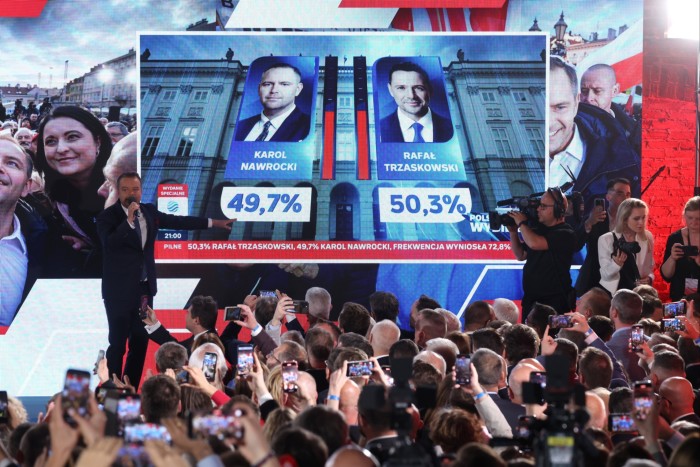

Nawrocki overturned opinion polls that placed Tusk’s candidate Rafał Trzaskowski, the Warsaw mayor, as the frontrunner throughout the campaign. Tusk’s candidate then narrowly won the first round and declared premature victory on a dramatic election night, based on initial projections that gave him a razor-thin lead.

Maria Skóra, a Polish visiting researcher at the European Policy Centre, a Brussels think-tank, said the defeat did not “come out of nowhere” and was “a red card for Tusk’s government”.

Tusk’s legislative agenda has largely been blocked by outgoing President Andrzej Duda, another PiS nominee, and a constitutional court stacked with PiS-appointed judges. Tusk initially responded by using an “iron broom,” most notably to take over forcefully the state broadcaster TVP that he accused of working as a PiS mouthpiece only days after taking office in December 2023.

Once opinion polls began showing voters growing disillusioned by the slow pace of reforms, Tusk moved to consolidate his own power base — even if at the expense of junior coalition partners — while waiting for Duda’s departure to make a fresh start.

“Tusk did a lot to marginalise his own allies, but based on some wrong assumptions,” said Adam Gendźwiłł, political science professor at Warsaw University.

Gendźwiłł said that Tusk also miscalculated by thinking smaller partners only won temporary gains in 2023, taking votes that could ultimately be won back under his Civic Platform leadership.

But the election exposed mounting weariness with the rivalry between Tusk and Kaczyński, whose two parties have defined Poland’s political landscape for two decades. Two-fifths of voters in the first round opted for candidates outside their duopoly, with many younger voters helping radical politicians gain on both sides of the political spectrum.

Anna Wójcik, a legal scholar at Kozminski University in Warsaw, said the result would challenge Tusk’s view of him “waging this battle with Kaczyński over the direction of Poland”. She expected “many moves within those coalition parties”, potentially with some trying to distance themselves from Civic Platform.

While early elections remain a distinct possibility, the threat of extinction may persuade smaller coalition parties to remain in government. Under Polish law, parties must secure at least 5 per cent of the votes to enter parliament, an increasingly precarious threshold for some of Tusk’s allies.

Tusk offered an apology for his government’s shortcomings shortly before the vote. But despite Sunday’s setback, Tusk — who is also a former president of the European Council — remains Poland’s dominant pro-EU politician.

His leadership within Civic Platform is unchallenged, and his ability to galvanise anti-PiS sentiment still resonates with parts of the electorate.

“This might sound paradoxical, but if there’s a doomsday atmosphere now, that still leaves Tusk as the only person on this side of the political scene perceived to be capable of saving Poland,” said Bobiński, the think-tank director.