The Novels We’re Reading in June

Books

The Novels We’re Reading in June

Peculiar forms of criminality, as seen from front-line Ukraine and Lagos.

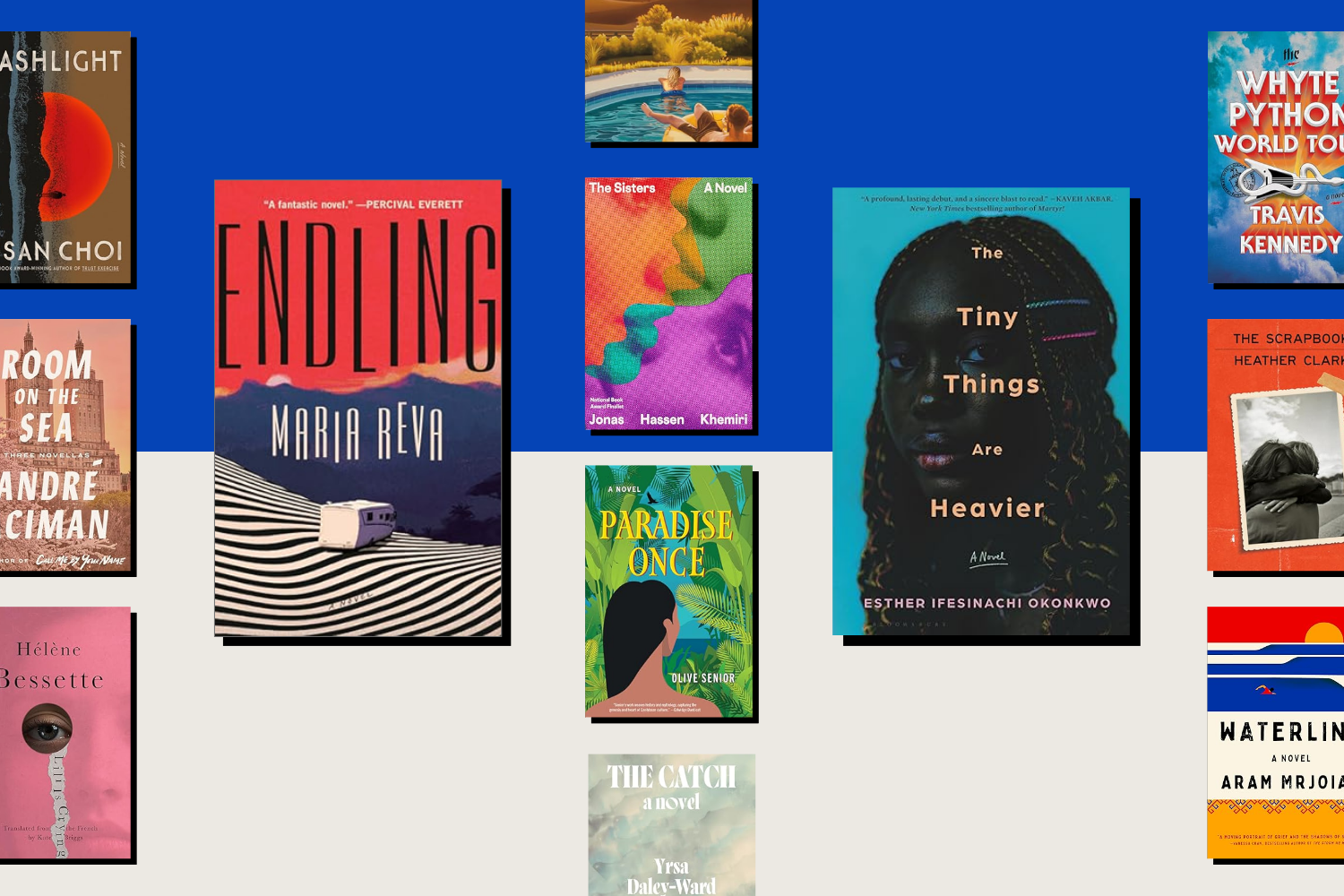

Publisher photos

This month, we’re taking madcap rides through Ukraine and Nigeria, where reckless decisions drive familial turmoil and quickly spiral out of control.

Endling: A Novel

Maria Reva (Doubleday, 352 pp., $28, June 2025)

This month, we’re taking madcap rides through Ukraine and Nigeria, where reckless decisions drive familial turmoil and quickly spiral out of control.

Endling: A Novel

Maria Reva (Doubleday, 352 pp., $28, June 2025)

The first time that Ukrainian Canadian author Maria Reva tried to write Endling was a bust. She already felt uneasy about the premise, which centered on two tired Ukrainian tropes: mail-order brides and topless female protesters. Then Feb. 24, 2022, arrived, and Russia’s full-scale invasion of her birth country made those subjects feel resolutely off limits. So Reva shelved it.

Luckily for readers, after some time, Reva returned to her debut novel—with more than a few metafictional and autofictional tweaks—and the result is nothing short of brilliance. Endling’s main storyline centers largely on Yeva, a loner scientist who funds her work rescuing rare snails from the brink of extinction by entertaining Western men on guided romance tours. (Her job is not to marry them, but to be the “shimmering bait” and “keep the bride-to-bachelor ratio high.”)

The snails under Yeva’s care aren’t particularly colorful or glamorous, but she’s drawn to these oft-ignored “humble victims of the Earth’s sixth mass extinction” that can hardly compete for sympathy with, say, the majestic northern white rhinos, the “belles of the extinction ball.”

Egged on by a pair of sisters who were raised by a famous feminist activist, Yeva agrees to use her mobile lab to kidnap 12 of the bachelors. (They settle for a “Last Supper size” of captives after Yeva shuts down the initial ambition of squeezing 100 of them into the trailer.) Once the women hit the road—bachelors and one last-of-its-kind snail in tow—the invasion begins, derailing their carefully planned plot, and that of the novel itself. In a sense, the novel ends and restarts a third of the way through, its timeline colliding with our own, the one where bombings are “looping infinitely” on our screens.

It’s an ambitious ploy that pays off handsomely. “A lot of writers now are grappling with how to write fiction in such a rapidly changing world. Much like the World Wars changed the course of art and thinking about art,” Reva recently told The Rumpus. “I think the novel is itching to be ripped apart again.” Her solution in Endling—to insert herself, or at least a character with her name, into the middle of the story—allows her to probe anew the role and ethics of storytelling in the face of great catastrophe. The result is a formally daring and wickedly funny novel that serves as a reminder of the possibilities, and necessity, of fiction.—Chloe Hadavas

The Tiny Things Are Heavier: A Novel

Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo (Bloomsbury, 288 pp., $28.99, June 2025)

From its first few pages, it would be easy to assume that The Tiny Things Are Heavier is yet another installment in the literary canon of dark academia. But although Nigerian writer Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo’s debut novel partially takes place on a U.S. campus, it transcends the boundaries of the university—and the United States—to ask painful questions about universal themes, such as human dignity and the limits of family loyalty.

The Tiny Things Are Heavier begins at a small airport in an Iowa town. Sommy, a 20-something Nigerian woman, has arrived in the United States to pursue a graduate degree in literature at the fictional James Crowley University. She struggles to integrate into her new surroundings, burdened by what she left behind in Lagos.

Shortly before Sommy’s departure, her older brother Mezie attempted suicide. Mezie had dreamed of a life in the United States, studying hard in pursuit of that goal: “He’d always clutched the American dream to his chest.” But when Mezie failed to get accepted to a U.S. college, he moved instead to Norway. He was ultimately deported back to Nigeria, and then came his overdose.

In Iowa, Sommy feels like she is living a life that should have been Mezie’s—and is weighed down by “the guilt of leaving him behind” in his moment of need. Feeling adrift, Sommy starts dating Bryan, an American MFA student who she learns is half Nigerian.

Bryan does not know much about his Nigerian father, who left the United States when he was a baby. But he is taken by Sommy and “her tales about Lagos, the people, the traffic, the hustle and bustle.” Bryan is also pleased to discover that they are both Igbo. Sonny sometimes wonders whether his “desire to know his father” is “the why of their relationship.” Over summer break, the pair decide to visit Nigeria so that Bryan can try to track down his dad. There, the novel turns from campus romance to international thriller.

In Lagos, Sommy reconnects with Mezie, only to find that their relationship has become irreparably tense; Bryan and Mezie don’t get along, either. Bryan’s attempt to identify his father, meanwhile, leaves him reeling. Also in the mix are Mezie’s visiting Norwegian girlfriend; Mezie’s ex-girlfriend, who seems determined to stir up drama; and Sommy and Mezie’s parents, who are “pretending like everything is fine” amid Mezie’s mental health crisis.

Hostility pulsates among all the characters—whether they are arguing about race, money, or love. Sommy’s mother is “quick to dish out cruelty,” while Mezie has a “dangerous ability to … unleash pain on women.” These enmities peak when the characters become involved in a shocking crime. How they each address their culpability sets the tone for the rest of the novel. They must weigh the pursuit of justice against the protection of family, and reverence for a flawed homeland against romantic love.

In tracing each character’s response to the crime, Okonkwo exposes uncomfortable sticking points in transnational identity and class, demonstrating how retrograde instincts often prevail in times of despair. “The truth,” Okonkwo writes, “is that we are all drawn to the familiar, whether or not we like it.”—Allison Meakem

June Releases, In Brief

A father’s disappearance unspools into a geopolitical whodunnit traversing decades and continents in Susan Choi’s Flashlight. André Aciman, of Call Me By Your Name fame, once again explores the vicissitudes of love in Italy and beyond in Room on the Sea: Three Novellas. French novelist Hélène Bessette’s 1953 tragicomic cult classic, Lili Is Crying, is translated into English by Kate Briggs. Sororal rivalry plays out across New York, Stockholm, and Tunis in Jonas Hassen Khemiri’s The Sisters. In Irish author Aisling Rawle’s debut, The Compound, a reality TV show in a near-future dystopia turns increasingly sinister.

In Paradise Once, Olive Senior, Jamaica’s former poet laureate, depicts the devastation of the Columbian exchange on the Caribbean’s Taíno people. Poet-memoirist Yrsa Daley-Ward forays into fiction with The Catch, a twisty family mystery set in London. A 1980s rocker realizes he might be an inadvertent international spy in Travis Kennedy’s The Whyte Python World Tour. Heather Clark’s The Scrapbook weaves a fictional tale of first love, family, and historical memory from a real-life World War II scrapbook. And more than a century after its end, the Armenian genocide casts a shadow over a Michigan family in Aram Mrjoian’s Waterline.—CH

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

This post appeared in the FP Weekend newsletter, a weekly showcase of book reviews, deep dives, and features. Sign up here.

Chloe Hadavas is a senior editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @hadavas.bsky.social X: @Hadavas

Allison Meakem is an associate editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @ameakem.bsky.social X: @allisonmeakem

Stories Readers Liked

In Case You Missed It

A selection of paywall-free articles

Four Explanatory Models for Trump’s Chaos

It’s clear that the second Trump administration is aiming for change—not inertia—in U.S. foreign policy.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.