Cyber crime is surging. Will AI make it worse?

For some patients, last June’s ransomware attack targeting Synnovis, a company that provides blood testing and transfusions to the NHS, was devastating. Staff had to cancel or postpone 12,000 appointments or elective procedures in the London area. At least two patients suffered serious long-term harm as a consequence. On the official 1 to 6 matrix for cyber incidents, the Synnovis attack was deemed to be a 2.

Britain has yet to experience the highest, a Level 1 attack, but the day seems to be getting nearer. Six months before the Synnovis attack, the Joint Parliamentary Committee on National Security Strategy had published a report on ransomware that included a stark warning: “There is a high risk that the Government will face a catastrophic ransomware attack at any moment, and that its planning will be found lacking.”

Cyber crime and cyber espionage long ago superseded traditional organised crime as a security and economic threat. It is a very serious business. But the threat is about to go to the next level in terms of scale and impact because of the revolutionary capabilities of artificial intelligence.

Cybersecurity companies, the police, the military, the intelligence services and think-tanks issue repeated warnings about the dangers of a lax approach to network security. The message can fail to get through for simple reasons — for business, it is often either cost or complacency; for the public, computers and IT security are witlessly boring.

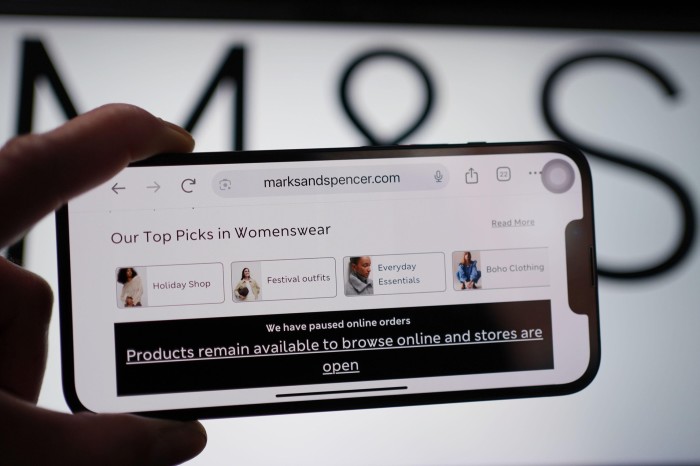

The media’s response to recent hacks against Marks and Spencer, the Co-op and Harrods indicate that if an attack impacts well-known brands in an industry vital to everyday life such as supermarkets, then it can generate both attention and concern. But among cyber security professionals, there was some frustration that the Synnovis attack didn’t receive the same scrutiny. Unlike the M&S attack, it led to serious physical harm and the consequences may well have included loss of life. Ironically, it is the shortage of Percy Pig sweets and Colin the Caterpillar cakes that turns heads. Empty shelves in supermarkets really bring it home to the public and trigger the government’s panic button.

Although by no means the only one, ransomware is among the most persistent and lucrative techniques deployed by criminal hackers. M&S saw £600mn wiped off the company’s market cap and an anticipated £300mn reduction to its annual profit because of the attack.

The group responsible, Scattered Spider, selects its targets carefully. Supermarkets are a particularly sensitive retail sector. Food’s perishability means that losses start to mount rapidly if companies cannot fulfil their deliveries after ransomware has frozen their systems. There is huge pressure on management and information security departments to find a rapid solution. When he discovered that M&S had been hacked late one evening, CEO Stuart Machin confessed to the Daily Mail that he went into shock. “It’s in the pit of your stomach, the anxiety,” he said.

In Britain, only about a quarter of victims admit to having been the target of successful ransomware attacks, according to police estimates. Many prefer instead to pay the ransom to avoid reputational damage. Paul Foster, who heads the cyber crime unit at the National Crime Agency (NCA), has some sympathy with business, especially with those small and medium-sized companies with fewer resources and tighter margins. “Businesses find themselves in a really difficult position when they’re subject to attacks such as the one to hit M&S and the Co-op,” he says. “But it is vital that they report it to law enforcement. We really can help.”

The NCA is worth listening to. It has chalked up some eye-catching successes in the battle against cyber crime. Foster was involved in last year’s takedown of LockBit, the most notorious Russia-linked hacking gang, which controlled 25 per cent of the ransomware market. Led by the NCA and the FBI, with assistance from nine other countries, the operation against LockBit revealed that in contrast to its promises, the group and its associates did not destroy the data of victims after a ransom had been paid. “They’re criminals after all,” continues Foster, “so why would anyone trust them?”

The scale of cyber crime has set off alarms around the world. In a dramatic intervention in late April at the RSAC in San Francisco, the world’s biggest annual cyber security gathering, John Fokker, a former high-tech investigator at the Dutch police and now head of threat intelligence at Trellix, the US cyber security giant, announced that “if cyber crime were a legitimate industry, it would be the third-largest economy in the world”, twice the size of Germany and looking to catch up both the US and China. According to industry estimates, global cyber crime will cost $10.5tn this year.

The UK’s annual Cyber Security Breaches Survey reports that about 85 per cent of attacks are facilitated by phishing, the persuasive social engineering techniques used to con people into giving hackers access to a system. Scattered Spider, a small, focused team believed to be native English speakers, would seem to conform to that pattern.

The common practice of outsourcing the administration of IT networks has also increased the so-called “attack surface”. Tata Consultancy Services, which provides technology services and IT infrastructure to M&S, is now conducting an internal investigation after the retailer announced that its system had been breached “through a third party”. TCS also provides technology services for the Co-op.

However serious the Scattered Spider campaign against the supermarkets has been, it pales against a hack from earlier this year. On February 21, the North Korean-sponsored Lazarus Group got away with the biggest heist in history. It gained access to the accounts of senior leaders at Bybit, one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchanges. In less than an hour, the thieves managed to extract 401,000 Ethereum coins, the second most valuable cryptocurrency after Bitcoin. In total, this amounted to $1.4bn dollars, $400,000 more than Saddam Hussein was able to filch when he looted the Iraqi national bank.

A complicating factor in trying to monitor and measure cyber crime is the presence of both state and non-state actors engaged in hacking. The Lazarus Group, for example, is a criminal organisation but it is entirely state-sponsored. In May 2023, Microsoft revealed the existence of Volt Typhoon, a state-sponsored Chinese hacking group, which has placed sleeper viruses in thousands of computers around the world. A little over a year later, researchers discovered Salt Typhoon, a similar operation that had penetrated nine US communications companies, including Verizon and AT&T. Such deep penetration of the US critical infrastructure sent shivers down the spine of Washington’s national security community.

Three elements have been driving the rise in cyber crime during the past two decades. The first is the technology itself. Ask any cyber security expert how it might be possible to make the internet safe and, almost without fail, they will answer: “Dismantle the entire thing and rebuild it from scratch.”

Rafal Rohozinski, the founder and chief executive of SecDev, a Canadian global risk and intelligence company, is more nuanced. “The internet was never built with security in mind — it was built for interoperability,” he says. “We spent 20 years making things work together and only belatedly worried about safety. What’s exacerbated this has been the absence of product liability laws or any kind of responsibility on the part of vendors — the people that actually build the technologies and devices that work on the internet — to put in any kind of safety.” The haphazard emergence of internet technologies, he explains, “has meant that the system has layer upon layer of vulnerabilities, ready for exploitation”.

This also represents a business opportunity for those in the security business. As Rohozinski notes: “Cyber security companies will convince you that they are your friend but essentially they are like giant leeches sitting on the back of the internet.” They can grow and grow, confident in the knowledge that the internet is intrinsically insecure. “If you want decent returns on your investments,” he concludes, “cyber security is one of the safest bets you can make.”

Bitcoin is the second great facilitator of cyber crime, ransomware in particular. Launched in 2009, it became the currency of choice for criminals when the dark web marketplace Silk Road adopted its use a couple of years later. To this day most drugs, child pornography and many small arms sold over the dark web are paid for with Bitcoin. As, of course, are the ransom demands of groups such as Scattered Spider.

The US claims for itself the right to jurisdiction for any transaction conducted anywhere in the world using US dollars. That does not apply to Bitcoin, giving criminals a layer of protection. However, as Bitcoin relies on open blockchain technology through which one can track all transactions, law enforcement around the world soon learnt to monitor illegal payments using the cryptocurrency.

This proved a huge assistance in tracking down cyber criminals. But as in so many aspects of cyber security, the “sword and shield” principle applies. As soon as the security industry finds a way of scuppering the attackers, the hackers quickly come up with a workaround.

In the case of Bitcoin, hackers developed so-called “mixers”, which jumbled up the identity of individual Bitcoins, thus obscuring which Bitcoins were involved in criminal transactions.

In the past five years, the barriers to entry into the cyber-crime market have been getting steadily lower. Thus the third reason behind the cyber crime increase is that there are many more players in the game. Inspired by the outsourcing of data storage and software into the cloud, cyber-crime groups from the Russian-speaking world such as LockBit established malware or Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS).

These criminal services are now easily available over the dark web. A wannabe extortionist no longer needs any technical ability to mount a campaign. Once they have successfully penetrated a network by using social engineering skills, they can buy or rent the tools for the job.

Voice phishing, as it is called, is shooting up the social engineering charts. According to CrowdStrike, a cyber security company, such attacks increased by 442 per cent in the second half of 2024. The reason for this is AI, which is not only able to write highly convincing fake emails but also creates voices with perfect local accents that can work off a script. Say goodbye to the supposed Nigerian princes offering you a cut of their millions, say hello to your chief executive asking you to pay an invoice to a new creditor.

ChatGPT and other large language models have guardrails that are supposed to prevent nefarious uses such as these. But in June 2023, as excitement was growing about generative AI, a developer announced the launch of WormGPT, a program that advertised itself as AI for criminals. Several major Generative Pre-trained Transformer programs are open source, meaning that anybody with the requisite coding ability can reproduce and alter this software. But all can be manipulated by “jailbreaking” — removing the guardrails. Although shortlived (largely because it priced itself out of the market), WormGPT pointed towards the future of crime on the net.

Last month, four researchers at the Ben Gurion University of the Negev revealed how they had developed a universal “jailbreak” attack that subordinated all major publicly available AI programmes, such as large language models, to their will. Their conclusions about what they termed Dark LLMs were chilling.

“Unchecked, dark LLMs could democratise access to dangerous knowledge at an unprecedented scale, empowering criminals and extremists across the world. It is not enough to celebrate the promise of AI innovation. Without decisive intervention — technical, regulatory, and societal — we risk unleashing a future where the same tools that heal, teach and inspire can just as easily destroy. The choice remains ours. But time is running out.”

As academics and developers around the world digest the implications of such findings, calls for the imposition of global regulatory standards to apply across AI programs are getting louder. The problem here is geopolitics.

The US and China are in a race to achieve superiority in artificial intelligence. With the launch of ChatGPT and other LLMs from 2022, the US was confident that it held a strong lead over their Chinese rivals. But then came the unveiling of the DeepSeek chatbot, developed at a fraction of the cost of the American versions, on the day of President Trump’s inauguration in January. The message was clear — China is in this race to win.

As we move into the next phase of AI development that would see the technology operate with much higher autonomous capability, a victory would lead to the widespread adoption of the winning model around the world. This implies significant economic, social and military advantages.

That competition is once more leaving regulation and security concerns behind in the name of innovation. The EU is attempting to impose a regulatory system on LLMs and new AI technologies. The Trump administration and Silicon Valley see this as a potential brake on their ability to defeat China in the tech war. The Americans and the Chinese hold the strong hands; the EU’s looks weaker.

Hackers are using LLMs for more than phishing campaigns. This year, a researcher from one of Europe’s most successful cyber security companies used AI from DeepSeek to successfully find two “zero-day” vulnerabilities in one of the world’s leading browsers — hitherto undiscovered bugs in a software program that hackers can exploit to access a system. A hacker in possession of a zero-day is sitting on a potential gold mine.

In this latest surge of innovation, however, what worries the cyber security industry above all else is the potential misuse of agentic AI. In contrast to simple LLMs, this technology can adapt to its environment, reason about complex situations and learn without human intervention. An agentic AI focuses on managing a single task but at levels of competence that are almost beyond comprehension.

According to Vasu Jakkal, the vice-president of Microsoft security, in the next two years agentic AI will take the technology “from level zero autonomy to level three autonomy”. In other words, AI is about to start thinking for itself. Speaking at the RSAC, Jakkal said: “We also know that threat actors are going to use agentic AI for their own benefits. We are already seeing some of this. They are using it to get more productive. They are using it to launch new kinds of attacks, whether it’s new vulnerabilities that they can find or it’s malware and variants of malware.”

Paul Foster of the NCA is similarly concerned. He points to research that has speculated how agentic AI could operate autonomously and assume all the functions of cyber-crime gangs: writing malware, devising and executing phishing campaigns, exfiltrating and encrypting data, issuing ransom demands and laundering Bitcoin payments.

The speed of innovation in the AI sector has reached a breathtaking level. But the degree to which these developments will expand or reduce the global threat level will depend on geopolitics. The growing tension between the US and China; the ability of the EU to assert its “digital sovereignty”, in the face of American and Chinese dominance; the willingness of Russia to continue hosting crime and espionage groups — these are the questions upon which the security of the internet will rise or fall.

Misha Glenny is rector of the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna and author of ‘DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia’

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning