The Last China Hand

Profile

The Last China Hand

Jerry Cohen has spent a lifetime trying to understand the People’s Republic.

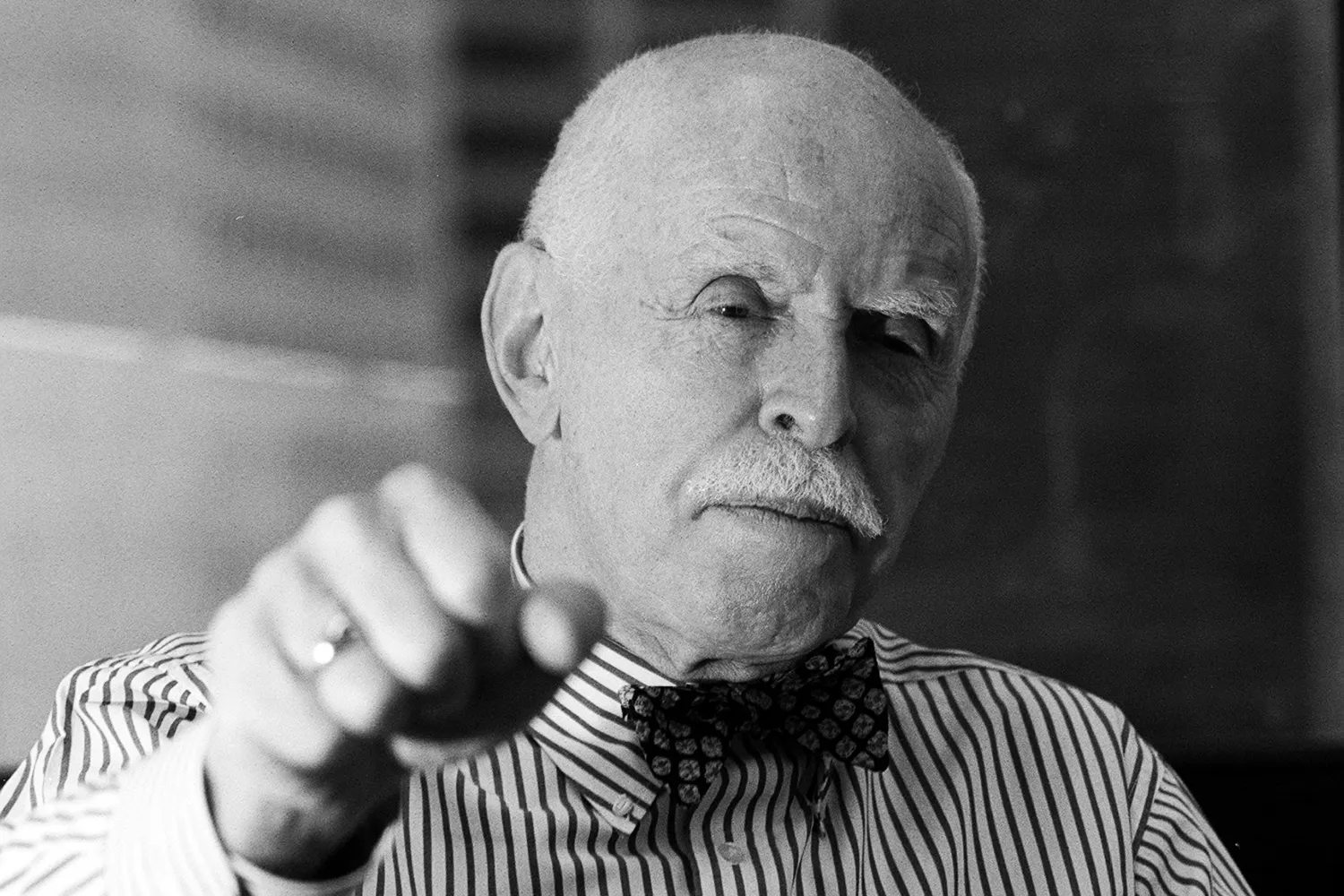

Jerome Cohen during an interview on Nov. 13, 2001. Robert Ng/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

Jerome A. Cohen, born July 1, 1930, may be the last active China scholar of his generation. He has spent nearly seven decades working on that relationship by vigorously debating law, trade, and human rights, all with a sense of urgency matched by a sense of humor.

The avuncular, bow tie-wearing Cohen—Jerry to his many friends—made it his life’s work to understand China well before Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to Beijing in 1971 that paved the way for the establishment of modern U.S.-China relations. His new memoir, Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law, outlines a life of rigorous intellectual balance and is essential reading to understand the evolution of the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

Jerome A. Cohen, born July 1, 1930, may be the last active China scholar of his generation. He has spent nearly seven decades working on that relationship by vigorously debating law, trade, and human rights, all with a sense of urgency matched by a sense of humor.

The avuncular, bow tie-wearing Cohen—Jerry to his many friends—made it his life’s work to understand China well before Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to Beijing in 1971 that paved the way for the establishment of modern U.S.-China relations. His new memoir, Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law, outlines a life of rigorous intellectual balance and is essential reading to understand the evolution of the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

In 1960, when few Western scholars were looking East, Cohen, then a young law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, started studying Mandarin and investigating the bones of Chinese law barely a dozen years after Mao Zedong declared the formation of a nation that, 75 years later, is the focus of a lot of fear in the West.

Cohen wanted to be a pioneer and intuited that if he was going to pass up a lucrative law practice, his incentives lay in academic freedom and a cohort of stimulating colleagues. His greatest influences were John K. Fairbank, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard University, and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, for whom Cohen also clerked—learned men who cultivated vast networks of their own students and protégés to keep tapped into youthful inquiry and hone their minds.

“I’ve ended up duplicating what they did,” Cohen said in his trademark baritone rasp, reflecting gratefully on reaping the harvest of his choices over a lunch at his Manhattan home last March. “I sit here every day and benefit from all the students of 60 years. That ain’t nothing.”

Cohen is a product, in his words, of lower-middle-class New Jersey. He rose—after undergraduate and law degrees from Yale University—to clerk for Earl Warren, then chief justice of the Supreme Court, the man who, importantly, led the desegregation of U.S. schools and, confoundingly, promoted the segregation of some 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Cohen then taught at Berkeley, Harvard, and New York University and helped lawyers and Communist officials in China shape much of the country’s modern legal code. Along the way, he advised President Jimmy Carter, Sen. Ted Kennedy, General Motors, Amoco, and Daewoo, among others.

Cohen (left) sits on stage during an address by U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy as he speaks to students at Hiroshima University in Japan on Jan. 11, 1978. Sadayuki Mikami/AP

When Cohen started studying Chinese, U.S. awareness of China was still impacted by the Korean War, a strong feeling that the Communists were hostile, and the fact that no Americans could go to China and no Chinese could come to America.

“To me, it was obvious China was going to develop further. We had too few specialists—nobody in my field of law and government. It was a very complex arena,” Cohen said. “How could I not be interested in China?”

The paranoias of the early Cold War described in Cohen’s memoir are echoed too often today, especially in places such as Florida, where moves to block land ownership by Chinese nearly became law in February 2024. (Cohen calls Warren’s spearheading the internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese descent a “black mark” on the history of the highest court in the land.)

As an undergraduate at Yale, Cohen said, “No, thanks,” when a CIA recruiter visited campus. One Yale classmate, Jack Downey, signed up with the CIA and would later be captured by China in Manchuria in November 1952. Cohen’s work over the ensuing decades to understand, rather than simply condemn, Maoist and Chinese legal thinking would prove key in negotiating Downey’s eventual release in March 1973.

“If, instead of studying China, I had gone to Washington in ’61, I would have probably worked for the CIA, too, and served McGeorge Bundy, John F. Kennedy and Johnson’s national security advisor,” Cohen said. “I, too, might have become a Vietnam warrior.”

Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law, Jerome A. Cohen, Columbia University Press, 384 pp., $38, March 2025

Instead, as his book reveals, Cohen and his Harvard colleague Jim Thomson (previously Bundy’s China specialist on the National Security Council, or NSC) opted out when Washington’s misadventures in Vietnam began in ’66, when the NSC sent Thomson to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) “to find out what the Chinese were doing there,” Cohen said.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who was planning a presidential bid, knew China was going to be a make-or-break question. When Thomson came back after two weeks and said the Chinese were “doing almost nothing in Vietnam,” Humphrey became furious, Cohen said.

The dominance of “yellow peril” fears after the loss of China and the Korean War is easy to forget. Kennedy and Johnson’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s saying that a billion Chinese with nuclear weapons were going to sweep over Southeast Asia was the voice that drove the U.S. State Department view on China in the early 1960s, Cohen said.

The book describes how Cohen and Thomson pushed back against that fear and worked with a group of scholars from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to recommend a new China policy to whichever candidate won the White House in 1968.

Those worries have returned in the shape of “China peril” narratives today. “Unfortunately, there seems to be a widespread agreement on anything that says, ‘We’ll compete and beat China’ and ‘defend against China,’” said Cohen, trotting out what he and other moderate voices wish for from The Oval Office: “Cooperation, competition, criticism and, for balance, containment.”

Cohen gives an address in Hong Kong on Dec. 12, 1978. Chan Kiu/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

“The next president has to try, through an understanding with China, to balance the four C’s,” Cohen said during our conversation last year, sounding at once adamant and exhausted. “We can’t fail on containment, but we can’t be content with containment. We obviously will compete with them, but we have got to cooperate. We have to benefit from their criticisms of us, and they have to take our criticisms more seriously. It requires a breakthrough in their mental capacity that could come about, perhaps, if we can get through to [Chinese President] Xi Jinping.”

Cohen was not happy with former President Joe Biden’s China policy. He feels that Americans should take the high road after the turbulence of 2020, when tensions soared over China’s handling of COVID-19, China expelled American journalists, both countries closed foreign consulates, and U.S. Secretary of State publicly called engagement with China a failure.. Cohen argues that the right path is people-to-people connection—reestablishing the Peace Corps in China, for instance, and reopening the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu, which was closed in retaliation for China’s closure of its Houston consulate in early 2020 following accusations of economic espionage and attempted intellectual property theft. . For decades, Cohen walked the walk, challenging his many accomplished students from China and the West to strive to understand one another.

Among the toughest issues is addressing China’s feelings about aid to Taiwan, a country that Americans back fiercely but barely seem to understand. Cohen writes of the journalist who asks an American subject, “What do you think about Taiwan?” The American replies, “I love Thai food!”

“Until recently, that was Taiwan’s problem,” Cohen said. “Now, thanks to [Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Taiwan and the China question have become very important.”

As much as Cohen has pressed for people-to-people connections, he always also has supported the staunch protection of human rights and has never shied away from publicly calling China out on its myriad transgressions, working tirelessly on behalf of Chinese who ran afoul of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and faced dire consequences, such as the now exiled, blind, “barefoot lawyer” Chen Guangcheng, to whom he devotes a whole chapter of his memoir.

Chinese activist Chen Guancheng speaks alongside Cohen at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York on May 31, 2012.Mario Tama/Getty Images

Cohen has sharp words for Beijing’s leaders, too. Chinese companies’ well-documented deployment of North Koreans and Uyghurs in labor camp conditions belies Beijing’s claim that its record protecting human rights is good and improving.

“We don’t really know enough. They’re so good at hiding things that come out eventually, occasionally. It hasn’t improved,” Cohen said. Yet even under the CCP’s absolute domination, Cohen notes and his book details, legal technical progress is being made.

“Chinese still have to deal with intellectual property. They still have to deal with contracts. They have to deal with treaties. There is a professional group in China—some of whom can’t speak now, can’t teach, can’t publish—but they’re still working to improve noncontroversial aspects of the legal system. So, it’s not as dead as one could infer from the well-advertised violations of international human rights,” Cohen said.

Cohen writes that parts of China’s legal system function with “considerable non-political autonomy” but that those areas are dwindling. Eastward, Westward details Cohen’s increased attention in recent years to the CCP’s use of arbitrary detention, not only against its own people, internally, but increasingly against foreign nationals.

On his doubtful days, Cohen says, one of his many prominent students, Jamie Horsley, the former head of Yale’s China Law Center and commercial attaché to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, tries to make him see that things in China are more complicated than mere wholesale repression.

“I looked to [the late] Alexei Navalny and Russian cases as a contrast with China, because it showed me that Russia really is an authoritarian state but China is techno-totalitarian,” Cohen said. “China has a much greater degree of repression—much more effective than in Russia, but Russia is studying hard how China does it.”

One story in the book is an apt metonym for Cohen’s work as a persuader and peacemaker. Cohen writes that the most fun he ever had was in settling a dispute that arose in setting up the Daya Bay nuclear power project, 43 miles from Hong Kong, in 1983-84, just as the British were negotiating the future of their colonial territory with Beijing.

Cohen during an interview at his office in New York on May 20, 2012.Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

A master of due diligence, Cohen peppered China’s chief negotiator to the point that he turned, Cohen recounted, and said, “Until we met you, we thought lawyers were paid by the hour, but now we think you must be getting paid by the question.”

Cohen appreciated the negotiator’s sense of humor and responded in kind. The key question in the negotiation was about which safety standards the Chinese would accept for building their first nuclear power project. Would they follow the higher, French standards that had fostered dozens of projects without a problem, or would they insist on the lower standards of the International Atomic Energy Agency? Cohen was not going to go for the latter. One day, Cohen pretended to give up and said, “OK, if we take your standards, the advantage is that maybe that will solve the future because it might blow up and affect Hong Kong.”

“You know, professor,” the negotiator said. “Sometimes I don’t like your humor,” to which Cohen quickly replied, “It’s no joke.” The Chinese finally yielded, opting for the safer standard, and Cohen said, “They’ve been lucky.”

Jonathan Landreth is an American reporter who has worked in Asia and the US since 1997.

More from Foreign Policy

-

Russian President Vladimir Putin looks on during a press conference after meeting with French President in Moscow, on February 7, 2022. The Domino Theory Is Coming for Putin

A series of setbacks for Russia is only gaining momentum.

-

The container ship Gunde Maersk sits docked at the Port of Oakland on June 24, 2024 in Oakland, California. How Denmark Can Hit Back Against Trump on Greenland

The White House is threatening a close ally with a trade war or worse—but Copenhagen has leverage that could inflict instant pain on the U.S. economy.

-

Donald Trump speaks during an event commemorating the 400th Anniversary of the First Representative Legislative Assembly in Jamestown, Virginia on July 30, 2019. This Could Be ‘Peak Trump’

His return to power has been impressive—but the hard work is about to begin.

-

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio greets employees at the State Department in Washington, DC, on January 21, 2025. The National Security Establishment Needs Working-Class Americans

President Trump has an opportunity to unleash underutilized talent in tackling dangers at home and abroad.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.