The Novels We’re Reading in April

This month, we’re reading about a listless Hungarian man and a struggling American academic with Indian and Iranian ancestry, both of whom find themselves at home nowhere.

Flesh: A Novel

David Szalay (Scribner, 368 pp., $28.99, April 2025)

This month, we’re reading about a listless Hungarian man and a struggling American academic with Indian and Iranian ancestry, both of whom find themselves at home nowhere.

Flesh: A Novel

David Szalay (Scribner, 368 pp., $28.99, April 2025)

After the publication of one of David Szalay’s earlier novels, a reviewer in the Spectator remarked, aptly, that “nobody captures the super-sadness of modern Europe as well as Szalay.” This holds true in the Hungarian English novelist’s latest book, Flesh, an unsparing portrait of one man’s life over many decades, from his upbringing in post-1989 Hungary to the ultra-globalized London of today.

Early in the novel, on a train home to Hungary after serving in the army in Iraq, Ishtvan, the protagonist, realizes that the things he witnessed abroad “have no reality here.” It’s a common enough observation for anyone who has left home for the first time, but Ishtvan can’t seem to escape this dreamlike detachment, a state that follows him as he leaves the remote housing estate he grew up in and tries to scrape by working security at a nightclub in London, before rising, almost as if by accident, up the social ladder.

Life always seems to be happening to Ishtvan; he’s propelled along by sexual urges (his own and others’), material desires, other people’s self-interest, and whatever political or geopolitical forces hover just out of sight. For much of the novel, this works out in his favor, with a rags-to-riches arc that would put most bootstrapping success stories to shame. But Flesh is marked by an ache that pervades social strata; Ishtvan shares a cramped house in London, with “no prospect of anything except more of the same,” and then later, his adopted world is filled with, as one character describes it, “money people and socialites.”

Szalay is especially attuned to the totalizing effect of money on human relationships. At one point, Ishtvan’s love interest tries to refute the idea that she only married her first husband, who inherited a Swedish electronics company, for his wealth: “What they didn’t seem to understand, she says, is how hard it is to say how much the money is or ever was a factor … It was that the money, insomuch as it was a factor, will have operated by making her find him actually more attractive as a person than she otherwise would have done, though to what exact degree of difference is obviously impossible to say, so that to even ask the question seems pointless.”

Genuine intimacy and human connection are hard to come by in this world. Although we see him through many of life’s most private moments, we are always at a remove from Ishtvan, who remains brusque and impenetrable (a character who is not especially fond of him remarks that he exemplifies “a primitive form of masculinity”). But in this cold, propulsive tale of estrangement and alienation, Szalay captures not just the utter strangeness, but also the possibilities, of modern life.—Chloe Hadavas

Liquid: A Love Story

Mariam Rahmani (Algonquin Books, 320 pp., $29, March 2025)

Writer Mariam Rahmani’s debut novel manages to include both summer romance and critiques of U.S.-Iran relations. In Liquid, cynical humor pairs with personal turmoil to make for a head-spinning ride through dating apps, academia, and the contours of Iranian American identity.

Liquid begins in 2017, when an unnamed woman narrator—whose professional bona fides and personal background mirror Rahmani’s—has a one-night stand on the beach in Los Angeles. She is an Indian Iranian American scholar of comparative literature, “fresh off a six-year PhD and just five months into a presidency that had decided to define itself by a Muslim ban.” Fast forward two years, and the narrator is floundering as an adjunct professor on the academic job market. “Defying the teleology of progress that is the promise of American life, finishing my degree had only made my life worse,” she reflects.

The narrator’s best friend Adam quips that, to make ends meet, she could “get hitched to someone with an inheritance.” With no sources of income lined up for the summer, she devotes herself assiduously to this project, aiming to go on 100 dates by fall. It doesn’t hurt that she studies “companionate marriage” and is concurrently writing a syllabus for a proposed course on rom-coms. Quickly, a spreadsheet is set up and dating app profiles are created. The narrator logs her every encounter with scientific urgency but has little success. She finds—in possibly the most relatable part of Liquid—that the apps are a cesspool.

Dozens of dates into her experiment, the narrator receives word of a family emergency and must pack her bags for Tehran. Liquid’s chapters go from being labeled with Western to Persian numerals.

In Iran, the hunt for a partner on pause, the narrator faces the realities of her parents’ own failing marriage. Her Sunni Indian mother lives in the midwestern United States and her Shi’a Iranian father in Tehran. “Neither … wore their wedding rings. But they were not divorced. Not technically,” she says. Her parents had a whirlwind, boundary-breaking romance as college students. But her mother became the family’s breadwinner, and her father “had fallen out of love with her from pride,” the narrator explains. “That was the problem with love stories: they ended with the beginning. Of my parents’ marriage, I’d only witnessed carnage.”

Tense family relations unfold against the backdrop of a changing Iran. The narrator never spares an opportunity to make a zingy remark about the country’s dysfunctional charm. “I scanned the women for the state of hijab law,” she says in the parking lot of Imam Khomeini International Airport. “Like tax evasion in the US, what you could get away with depended on who was president.”

At times, her commentary is more serious: Dealing with a family member’s illness, she discovers that Iranian public hospitals have struggled to procure enough CT machines due to U.S. sanctions. Still, “in my position—uninsured—[I] would’ve fared even worse in America,” she concludes. She is also troubled by the racism her mother faces in Iran, observing that every culture “had someone to fetishize and oppress.”

With the reflective capacity that can come with being far from home, the narrator decides to reevaluate her search for love. “What was marriage but tenure?” she asks. The latter may have tremendous appeal for an academic, but the search for the former cannot be rushed in the same way, at least if it is to endure.—Allison Meakem

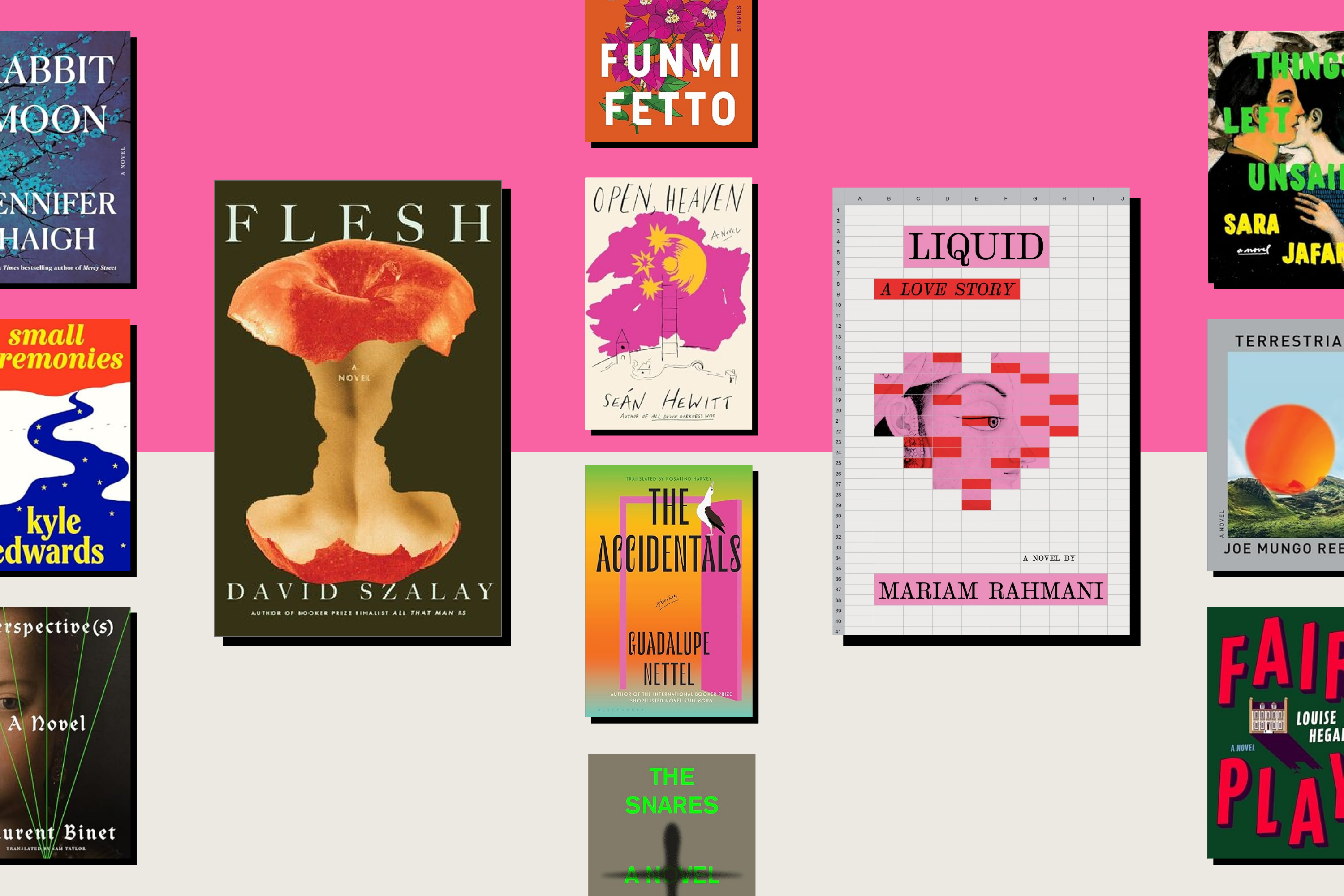

April Releases, in Brief

A fractured American family converges in a Shanghai hospital in Jennifer Haigh’s Rabbit Moon. Anishinaabe writer Kyle Edwards’ debut, Small Ceremonies, tells a coming-of-age story set among a group of Indigenous hockey players in Winnipeg. A whodunnit meets the political intrigue of Renaissance Florence in French author Laurent Binet’s Perspective(s), translated by Sam Taylor. Irish poet Seán Hewitt’s foray into fiction, Open, Heaven, is a tale of first love in the north of England. Mexican short story master Guadalupe Nettel’s collection, The Accidentals, is translated into English by Rosalind Harvey.

In Rav Grewal-Kök’s The Snares, a Punjabi American lawyer joins a mysterious new U.S. intelligence agency in the wake of 9/11. Funmi Fetto’s short story collection, Hail Mary, offers vignettes of the lives of nine Nigerian women. A British Iranian woman navigates the vicissitudes of her 20s in Sara Jafari’s Things Left Unsaid. Joe Mungo Reed’s Terrestrial History traverses coastal Scotland and a human settlement on Mars. And a jazz age-themed murder mystery party goes awry in Irish author Louise Hegarty’s Fair Play.—CH

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Chloe Hadavas is a senior editor at Foreign Policy. X: @Hadavas

Allison Meakem is an associate editor at Foreign Policy. Bluesky: @ameakem.bsky.social X: @allisonmeakem

More from Foreign Policy

-

An illustration shows a golden Cybertruck blasting through a U.S. seal of an eagle holding arrows and laurel. Is America a Kleptocracy?

Here’s how life could change for the rich, poor, and everyone in between.

-

The flag of the United States in New York City on Sept. 18, 2019. America Is Listing in a Gathering Storm

Alarms are clanging at the U.S. geographic military commands around the globe.

-

U.S. President Donald Trump shakes hands with Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts during Trump’s inauguration in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Judicial Crisis Is Uniquely Dangerous

But other democracies provide a roadmap for courts to prevail over attacks from the executive branch.

-

An illustration shows a golden Newtons cradle with Elon Musk depicted on the one at left and sending a globe-motif ball swinging at right. Elon Musk’s First Principles

The world’s richest man wants to apply the rules of physics to politics. What could go wrong?

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out

Change your username:

CANCEL

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.