Generative AI models are skilled in the art of bullshit

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

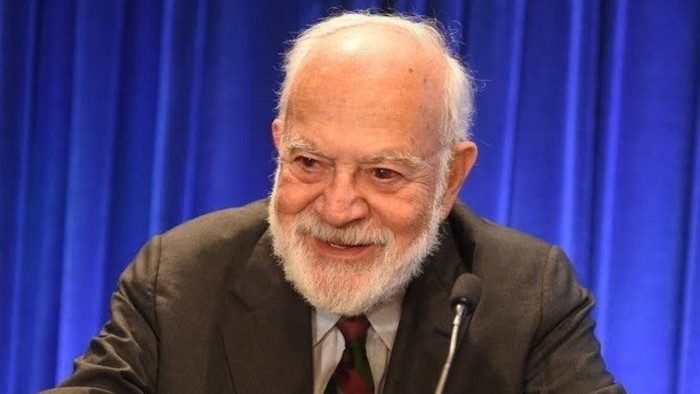

Lies are not the greatest enemy of the truth, according to the philosopher Harry Frankfurt. Bullshit is worse.

As he explained in his classic essay On Bullshit (1986), a liar and a truth teller are playing the same game, just on opposite sides. Each responds to facts as they understand them and either accepts or rejects the authority of truth. But a bullshitter ignores these demands altogether. “He does not reject the authority of truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.” Such a person wants to convince others, irrespective of the facts.

Sadly, Frankfurt died in 2023, just a few months after ChatGPT was released. But reading his essay in the age of generative artificial intelligence provokes a queasy familiarity. In several respects, Frankfurt’s essay neatly describes the output of AI-enabled large language models. They are not concerned with truth because they have no conception of it. They operate by statistical correlation not empirical observation.

“Their greatest strength, but also their greatest danger, is their ability to sound authoritative on nearly any topic irrespective of factual accuracy. In other words, their superpower is their superhuman ability to bullshit,” Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West have written. The two University of Washington professors run an online course — Modern-Day Oracles or Bullshit Machines? — scrutinising these models. Others have renamed the machines’ output as botshit.

One of the best-known and unsettling, yet sometimes interestingly creative, features of LLMs is their “hallucination” of facts — or simply making stuff up. Some researchers argue this is an inherent feature of probabilistic models, not a bug that can be fixed. But AI companies are trying to solve this problem by improving the quality of the data, fine-tuning their models and building in verification and fact-checking systems.

They would appear to have some way to go, though, considering a lawyer for Anthropic told a Californian court this month that their law firm had itself unintentionally submitted an incorrect citation hallucinated by the AI company’s Claude. As Google’s chatbot flags to users: “Gemini can make mistakes, including about people, so double-check it.” That did not stop Google from this week rolling out an “AI mode” to all its main services in the US.

The ways in which these companies are trying to improve their models, including reinforcement learning from human feedback, itself risks introducing bias, distortion and undeclared value judgments. As the FT has shown, AI chatbots from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, xAI and DeepSeek describe the qualities of their own companies’ chief executives and those of rivals very differently. Elon Musk’s Grok has also promoted memes about “white genocide” in South Africa in response to wholly unrelated prompts. xAI said it had fixed the glitch, which it blamed on an “unauthorised modification”.

Such models create a new, even worse category of potential harm — or “careless speech”, according to Sandra Wachter, Brent Mittelstadt and Chris Russell, in a paper from the Oxford Internet Institute. In their view, careless speech can cause intangible, long-term and cumulative harm. It’s like “invisible bullshit” that makes society dumber, Wachter tells me.

At least with a politician or sales person we can normally understand their motivation. But chatbots have no intentionality and are optimised for plausibility and engagement, not truthfulness. They will invent facts for no purpose. They can pollute the knowledge base of humanity in unfathomable ways.

The intriguing question is whether AI models could be designed for higher truthfulness. Will there be a market demand for them? Or should model developers be forced to abide by higher truth standards, as apply to advertisers, lawyers and doctors, for example? Wachter suggests that developing more truthful models would take time, money and resources that the current iterations are designed to save. “It’s like wanting a car to be a plane. You can push a car off a cliff but it’s not going to defy gravity,” she says.

All that said, generative AI models can still be useful and valuable. Many lucrative business — and political — careers have been built on bullshit. Appropriately used, generative AI can be deployed for myriad business use cases. But it is delusional, and dangerous, to mistake these models for truth machines.